The Object on the Wall

Over the past decades, the photograph itself, the object on the wall, has become more important. Why is that? I actually think there is no simple answer. Instead, we seem to be witnessing several developments coming together at the same time. (more)

Conventional wisdom would have it that we really only have the Struffkys (Thomas Struth, Thomas Ruff, and Andreas Gursky) to blame for the fact that print sizes have exploded. To a certain extent, this is true. The Düsseldorf colour crowd required large prints for their photographs so that a viewer would actually be able to see all the details in them. What is more, artists like Andreas Gursky placed themselves into the tradition of painting. If you look at Albrecht Altdorfer’s The Battle of Alexander at Issus (1529) and then view Gursky’s Madonna I (2001), you’ll understand easily what’s going on here (I owe this insight to Nina Zimmer’s Pyongyang: A State of Exception, in Andreas Gursky, Hatje Cantz 2007).

The Struffkys would not have been able to do what they did (and still do) had there not been an actual way to produce those large colour photographs. Needless to say, any artist interested in large colour prints could have simply employed the methods advertizers have been using for many decades, and quite frankly I’m slightly surprised nobody seems to have done that. I’m just very slightly surprised, though, because of course there is the market, and you can’t possibly sell a commercially printed poster for the kind of money you can sell a Grieger photograph for. And even if we leave the market aside, I can see why an artist would want a “real” photograph on the wall and not a poster or billboard-style assembly of smaller panels.

Seen in light of what the photographs are intended to do, the huffing and puffing about Struffky print sizes comes across as being, well, a bit pointless: If artists want to explore photography using large prints, why would that be so wrong? Just look at, say, Richard Avedon’s enormous prints, currently on view at Gagosian in NYC (if you haven’t seen the show and have the chance to do so don’t miss it!). The large prints are about 100 by 240 inches (2.5 by 6m for the metric part of the world). The whole debate about print sizes seems a bit more blown out of proportion than the objects in question themselves.

But it’s not all about size, of course. There is the art market, which has been rapidly expanding over the past decades, too, just like the incomes of the 1%. And what artist would not want a piece of that pie? There are even print re-issues or re-prints or whatever you want to call them. You probably have heard about a collector filing a lawsuit because inkjet re-prints of older photographs were sold at inflated sizes and prices recently. Photography is now part of the art world, and that means and includes huge prices for the images produced by a small number of artists deemed worthy to be included in this kind of game.

There is a flip-side here, though: What exactly are collectors paying for? I think there is a psychological problem here. It’s probably easy to understand why you might fork over much more money for a print that’s much larger than an earlier version. But as we all know, the rising tide has lifted all boats, at least as far as print sizes are concerned (sales might be a very different matter). If you got the right reputation you probably don’t have to worry about justifying the price tag for what essentially is a mass-produced high-quality poster on nice paper (“the right reputation” here mostly means those photographers who have found access to the art world and who are not even viewed as photographers any longer). But what about everybody else? How do you justify asking a lot of money for a single piece of paper?

The answer is surprisingly easy to get: Just go to a gallery and have someone explain to you the work on the wall. Galleries have a pretty bad reputation, but there are quite a few photography galleries where the owners will be happy to talk about the work. What you will find is that a lot of the talk involves process. Process seems like an easy way to justify high prices. If an artist had to toil over a print for many hours or, better still, if the print is one of a kind (oh boy oh boy oh boy!), now there is a great way to justify high prices. I find it interesting how over the past few years so much process-oriented work has found its way into commercial galleries (Let’s be very clear here: Galleries don’t exhibit work based on artistic merit. Galleries exhibit work they think they can sell. Which is fine. That’s how that system works).

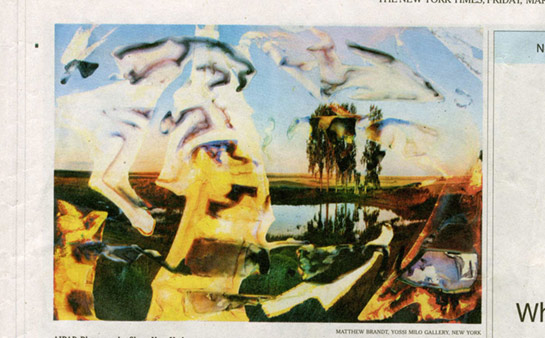

So I think the fact that there is so much process-based photography in galleries is in part fueled by the market, by market psychology: It just makes it easier to sell an expensive photograph if it’s not just some mass-produced print. On the other hand, there clearly is a very strong backlash against the digital revolution, with more and more artists embracing non-digital, process-oriented photography. Think Matthew Brandt or Marco Breuer. The image on top, from Brandt’s website, struck me: Here we have a photograph of part of a newspaper that is showing a reproduction of photograph that, as an object, has been physically transformed (try counting how many times you’re here flipping back and forth between the images and the object!). That aside, I did enjoy both shows very much (just like the Avedon one). For process-oriented images to work for me, I need to be convinced that the process is not just some gimmick, that, instead, the process adds something to the image. In other words if you took the process away you would lose more than just the application of that process. In Breuer’s case that was obvious, in most of Brandt’s it was too.

None of what I talked about here is a chicken-and-egg problem (let’s ignore the fact that we have more than two things to consider here: size, technology, the market, the backlash against digital, etc.). All of these things happened at the same time, and I’m actually reluctant to say that, well, it was this development that caused everything else. There doesn’t seem to be any simple causality here. I suspect that we will see quite a few other changes over the next few years, as some aspects will fade away or produce a dead end. If you’ve seen the last Andreas Gursky show at Gagosian, you already know that the artist has reached his artistic dead end: You can zoom out until you see a whole ocean, and you end up with a resounding Seinfeld moment: It’s about nothing. A large artistic failure - the consequence of, possibly, trying too hard to explore something that already a few years back seems to have totally run out of steam (isn’t it curious how Thomas Struth and Thomas Ruff both have avoided the problem?).

We’ll see where the photograph as an object on the wall will go. It’s never quite static, though. The object on the wall always seems to reflect technical possibilities, artistic vision and abilities, as well as the market, that monster looming over everything. Onward! Let’s see some more objects on the wall!

By

By