The Internet as a Photography Archive

Earlier this year, social-media behemoth Facebook announced that every day, its user were uploading 300 million images per day. That’s a pretty impressive number, the relevance of which, I think, is debatable, though. Regardless of what you make of the number, it’s fairly obvious that photography is being widely used. It might be worthwhile to point out that the vast majority of photographs created on this planet are not being produced by artists, professionals, or academics - unlike the vast majority of writing about photography. So when I read that someone writes how people mistrust photography I always wonder why there are 300 million new photographs on Facebook every day when nobody trusts photography. That aside, Facebook and the internet as a whole appear to be a pretty spectacular archive or library of photographs. This is where it gets interesting. (more)

The usefulness of any archive (or library) is essentially determined not by its size, but by its accessibility. Accessibility here includes two factors, namely first, whether or not one can access the material at all, and second, how easy one can find something, especially if one is looking for something that might or might not be very specific.

Seen in this light, the internet is a pretty bad archive. Access to the photographs on Facebook is very severely limited, for all kinds of reasons, many of which make a lot of sense. If you do not have a Facebook account, you won’t be able to access much, if anything. If you do have a Facebook account, you still need to be “friends” with many users to be able to see their photographs. There are all kinds of reasons why restricting access to these photographs is a very good idea.

But viewed as an archive, Facebook’s image database is essentially useless for a general user. Another way to phrase this would be to say that while there might be 300 million new photographs on Facebook every day, the vast majority of them will remain invisible to most people - this is essentially the very same situation that existed fifty years ago when amateur photographers took a lot of pictures (way less than today, of course), but they would never be seen by a wider audience. And let’s be more specific: Most of the photographs uploaded today not only will never be seen by a wider audience, it’s actually impossible for a wider audience to see them - unless special access is created to them.

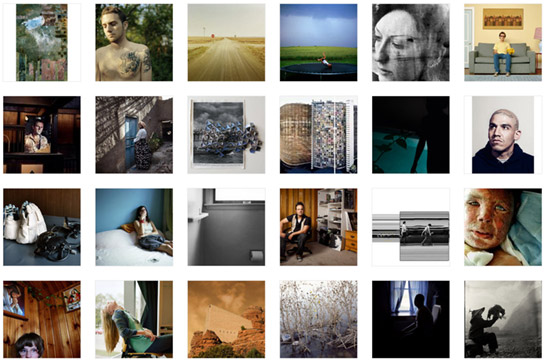

What this means is that when we talk of the internet as an archive we might want to add it’s everything except Facebook (and, possibly, some other websites that also restrict access). You might wonder why I’m so interested in this aspect of the web. The reason is very simple. When I started compiling photography information on this website, the original (and main) motivation was to make looking for photography online easier. Needless to say, the various archives you can find on this site only contain the information I added. But one of the things I have been thinking about and working on for all these years also is to make access to this database easier and more convenient. When you go to the different “Photographers” archives, for example, you get a thumbnail view of their contents. Of course, you can also search for names.

But Conscientious still is a very small archive, compared with the web, and as I said its goal never has been to be representative of photography as a whole. You’d imagine the internet itself would serve this purpose better. Does it?

As it turns out, having spent quite a bit of time on Google Image Search looking for photographs to use for, say, a “history of photography” class I taught this past spring, the usefulness of the internet to find photography still leaves a lot of room for improvement. Let me give you some examples (please also see the images that come along this article).

If you type in “photography,” Google Image Search will give you a useless smattering of stuff, plus the information that “related searches” are “newborn photography,” “digital photography,” “photography camera,” “wedding photography,” “nature photography,” and “photography love.” It’s fairly obvious that a search term as generic as “photography” would not be very useful. So the first rule of looking for photography online is that the user needs to be specific (in a library in our physical world, a lack of specificity wouldn’t be a huge problem, since there would be a “photography” section).

If you type in “contemporary photography,” things improve somewhat, even though the first-page results all in all are less than impressive. So “contemporary photography” still is not specific enough. How about “Robert Capa Falling Soldier”? Surely looking for a very well-known photograph must yield crystal-clear results. The first page of the search results indeed leaves very little to be desired. In addition to the actual photograph, you also get a photograph of Robert Capa plus a photograph of a young woman looking at the photograph you were looking for. Plus, there is a photograph of a sculpture created after the photograph.

Page 2 then adds all kind of other stuff. You get a copy of Robert Capa’s famous D-Day photograph. There also are Eddie Adams’ famous photograph of the execution of the Vietcong, a photograph of a snow-covered car, and a photograph from the Iranian revolution in 1979 (plus three more images that I can’t quite make out). You can say whatever you want, but the second page of the search for one of the most iconic photographs of the 20th Century already yielding completely different photographs is less than impressive.

Page 3 then goes completely bonkers, with the majority of images having nothing to do with the actual photograph. There is, for example, Edward Steichen’s 1904 “The Pond - Moonlight.” Or a colour photograph of three girls playing soccer. Say what?

Try playing this game with photographs that are not famous, or try playing this game with photographers who are not famous (or who live in places where the internet isn’t used quite as widely as in the Western world), and you’re in trouble. When preparing my photo history class, what I learned was that I was more certain to find a photo of a naked woman amongst the search results than the actual photograph if, for example, the artist had photographed in the 19th Century, say (and wasn’t well-known). And it’s not even the remote past or remote places (try finding African photographers online!) that make things iffy. Even photographers from the not-so-remote past often are invisible online.

What we have here is a problem caused by two factors. The first factor is that the images on the web are often badly indexed (hence the various Robert Capa misidentifications). The second factor is what scientists call a “selection bias”: You essentially can only look for image online that exist online. Of course, that’s obvious. But the selection of photographs online is biased in all kinds of ways.

My point here is not to say the internet is terrible for photography. It’s actually quite a bit better than when I started compiling this website out of sheer exasperation over the state of photo affairs online. But there is still tremendous room for improvement. In particular, if you think that the internet offers a representative view of photography you are sorely mistaken. The internet offers a representative view of the photography that is deemed good or valuable enough to be online.

That said, the internet often offers amazing search results. For a class I’m teaching this fall, I was looking for photographs of US soldiers. I typed in “US soldier” in Google Image Search. Much to my surprise the search results contained a considerable number of photographs that show US soldiers interacting with children or teenagers, typically in places like Iraq of Afghanistan. So a very generic search term - I had wanted it to be generic, to see, well, generic images - yielded a very specific result about how US soldiers are often portrayed in war zones: Interacting with children or teenagers. Once you factor in how Google ranks its search results, you get a pretty interesting commentary on our media and on what people want to see (I’ll leave it up to Michael Shaw to dig deeper into this).

By

By