How to tell a story with pictures

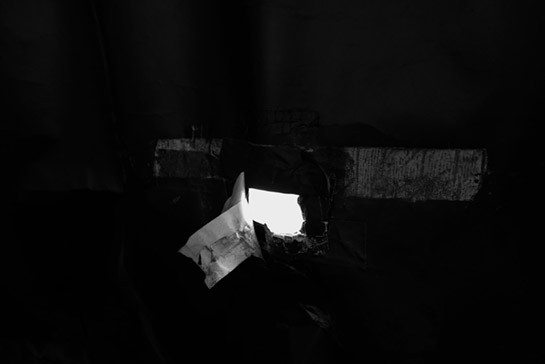

If I wanted to tell a story with pictures, just with pictures, how would I go about that? I could probably give you one photograph (see above) and tell you that’s my story. Chances are you wouldn’t take that for much of a story. And you’d probably be right, even though some photographers manage to tell stories with single pictures. But for the most part, we think of photographs as something else, not as stories, but as facts or documents. Or maybe it would be better to state that we think of photographs more as facts than as stories. This was summed up by Aaron Schuman who stated: “A photograph is only a minute fragment of an experience, but quite a precise, detailed, and telling fragment. And although it might only provide little clues, the photographer is telling us that they are very important clues.” (more)

A “minute fragment of an experience, but quite a precise, detailed, and telling fragment” might look like this:

Needless to say, this is not a photograph. It’s a dot, a schematic illustration of the idea of a “precise, detailed, and telling fragment.” How do you tell a story with just one dot? You don’t. You can’t. You need something else. We’re in business if we add another photo, which then gives us something like this:

Well, we’re almost in business. But we got something to work with. We now have two fragments of the world that might or might not relate to each other. Putting these two photographs together - that’s the storytelling. The relationship between them - that’s the story (assuming we’ll stick with two dots, for reasons of simplicity).

We might as well admit now that photographs don’t tell stories the way words do it. Words tell stories very, very slowly. You need to read them one at a time, and the story then slowly builds. A photograph, in contrast, is not the equivalent of one word. If we stay with Schuman’s phrase, a photograph is “a minute fragment of an experience, but quite a precise, detailed, and telling fragment.” Thus looking at one photograph after another would be to read a novel by somehow taking in larger chunks of pages at a time. You wouldn’t read one word after another, you’d somehow read 20 pages at once and then 30 pages etc. Not that there actually is a correspondence between chunks of pages in a novel and a photograph (there might be), but you get the idea.

On top of that, you can look at two photographs at the same time, which would amount to simultaneously taking in those 20 and 30 page chunks of pages at the same time. Trying to understand photographic storytelling by looking at storytelling with words leads to all kinds of problems, the main one being that it makes no sense. So let’s not do that1. Let’s stick with pictures.

Let’s go back to Schuman’s “minute fragment of an experience, but quite a precise, detailed, and telling fragment.” Is that really what photographs are? I don’t want to go too much into the semantics here, but I question the use of “precise” and “detailed,” even “telling.” Photographs, after all, have no meaning on their own. On their own, with nobody looking at them, photographs are nothing. Once someone looks at a photograph, a meaning of some sort will arise. That meaning, crucially, depends on both the viewer and the conventions of seeing the viewer is familiar with.

Let’s go back to words briefly. The term “candy bar” has a very specific meaning that we essentially all agree on. If you don’t agree with that specific meaning, the sentence “I really enjoyed eating that candy bar” might make no or a very peculiar sense to you, whereas everybody else understands very well what I am saying (mind you, not trying to say in this case). Of course, we just agreed on the fact that words don’t operate like photographs. If we go back to the 20-page chunks from a novel, say, we’re a little closer to what we’d need to understand. In all likelihood, most people will “understand” those twenty pages in more or less the same way, getting the main gist, whatever that might be (assuming there is one).

But we really have to stick with a novel - as opposed to twenty pages of non-fiction writing. It’s easy to see why that is: You just need to take a bunch of people, have them look at the same photograph and then ask questions until everybody is willing to open up and talk about all the various details s/he sees. In all likelihood, you’ll be amazed about the variation in seeing. The variation in seeing actually belies the “precise, detailed, and telling fragment” Schuman was talking about. There is a fragment, and it might be somewhat detailed, and it might be telling, but usually it’s not quite as precise as you want to think, and it might be telling in very different ways for different people. So schematically, more often than not, photographs look like this:

which transforms our two photographs into something like this:

Now you notice that the distance between those clouds actually matters. In the illustration I’ve chosen - the equivalent of the two dots - the two clouds overlap ever so slightly. Photographs can do that. In fact, that is where a lot of the art of storytelling with pictures is located: “a minute fragment of an experience” (back to Schuman’s term) might overlap with another one in all kinds of ways - slightly, very much, or, possibly, not at all. It’s easy to see how if there is an overlap then there is a story - the two fragments obviously are related, and if anything that is something our brains will pick up on.

If you think of two photographs as two overlapping clouds with undefined boundaries overlapping your worries about how to get from this to that, from here to there, from this one photo to that one photo, might dissipate a bit: There suddenly is no need to create a bridge or connection any longer. It’s already there.

This is not to say that two photographs always operate like two overlapping clouds. But we’re talking about storytelling with pictures here, and the crucial first step of understanding how stories can be told with pictures is to understand photographs. Minute fragments of experiences they might be, but they often (usually?) aren’t as precise or detailed or telling as many photographers think they are. And that is exactly your hook to create stories with them.

(to be continued: part 2, part 3)

top image: JM Colberg, Untitled, from Cantos

1 As an aside, comparing photographs to poems isn’t much better.

Update (17 October 2012): This is a corrected version of the original piece. In the original version the main quote had been mistakenly attributed to Alec Soth, from his conversation with Aaron Schuman. But it had been Schuman who used it. My apologies for the confusion!

By

By