Review: Welcome to Springfield by Michael Abrams

It is no secret that vernacular photography has moved center stage. To a large extent, this is probably due to simple nostalgia, the longing for the better times in the past that, in reality, never existed that way (a similar argument can be made to in part account for the popularity of Instagram filters, which now have even crept into photojournalism). But beyond that, there is the fact that vernacular photography shows you a world you did not have access to: The private lives of ordinary people (if I ran for office in the US I’d use “regular folks”). This is most interesting. While vernacular snapshots are becoming ever more popular, on Facebook people are now willingly sharing their formerly private photographs. To be more precise: A usually sometimes more, sometimes less carefully edited selection of those photographs. The age of narcissism has spawned the parallel age of voyeurism.

In the context of art, vernacular photography has been playing a role for quite some time. Many photographers have been collecting such images for a long time, be it in the form of vintage postcards, be it in the form of actual photographs. Collecting usually (often?) includes a form of curation, in that as a collector you select and buy around often very specific ideas. In part this is because there simply is too much stuff out there to collect it all (unless you’re a hoarder, in which case you have a problem). But the thrill of collecting is also tied to finding another piece for that unfinishable puzzle you’re working on. The collection, that’s your puzzle, which can - and usually will - expand seemingly forever. But not every piece fits. The thrill is thus in part the process itself, the often frustrating search for yet another photograph that fits the criteria.

Or maybe it’s just me collecting photographs that way. Regardless…

Compiling vernacular photographs into the form of a book requires at least that aspect of curation I outlined above. Take, for example, Boring Postcards. Then again, strict curation is maybe too strict a criterion. You can also collect seemingly random photographs and work with them using text, creating something like Wisconsin Death Trip. What unites these seemingly so different books is the aspect of authorship: To make a good book using vernacular photographs requires careful and smart authorship.

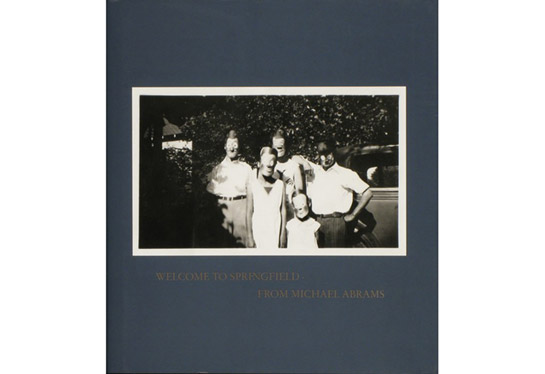

Some time ago, I reviewed Dive Dark Dream Slow by Melissa Catanese. Another recent example is provided by Michael Abrams’ Welcome to Springfield (you can find the publisher’s listing here). Unlike the former, the latter really hones in on the aspect of getting access to people’s private lives, in particular the things that even in the age of Facebook usually remain private (there are exceptions, of course, but let’s take them for what they are).

The book takes you to Springfield, that quintessential American town that could be anywhere. And not just that, it takes you not just to that town, it takes you into the homes of people who live there, and in particular into their bedrooms (occasionally, a living room or kitchen will do as well - people are flexible, after all), contrasting the private and the public lives people lead. A spread might show a photograph of a nude woman, lounging on a bed (with leopard print wall paper in the back!) and posing for the photographer, who, we must assume, might have gained access by means other than an ad in a newspaper. On the other side of the page, group of incredibly grumpy looking people, who appear to be family members, pose for a photograph outside. And so that story unfolds, the good American life, where the states of undress and awkward are never that far.

Welcome to Springfield is a smart and fun book, edited and designed very well. Crucially, the appeal of the vernacular photographs and of the story told with them never rubs off. Recommended.

Welcome to Springfield, photographs edited by Michael Abrams, short story by Gerry Badger, 156 pages, Loosestrife Editions, 2012