The Curious Tale of the Three Creepy Old Men

The other day, I went to see an exhibition called The Tireless Epic at The Hague Museum of Photography. The show features the work of Miroslav Tichý, Gerard Petrus Fieret, and Anton Heyboer. You’re probably familiar with the first artist, but the other two might be a bit more obscure (there certainly isn’t much to be found online - not that that means anything). I had never heard of them. So I was curious to find out more. I found three creepy old men. Actually, that’s not quite correct, but that’s certainly how it was presented. (more)

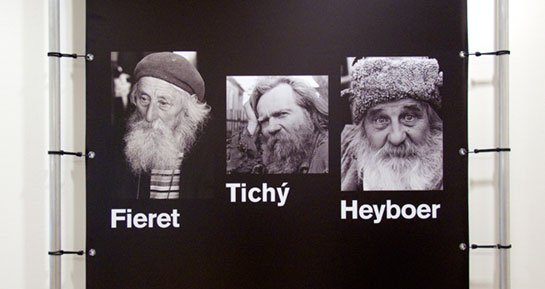

The above photo is the banner outside the exhibition hall, and if you found my calling these three photographers “creepy old men” somewhat odd, maybe the photo will explain things a little bit. What is particularly interesting, what needs to be noted is that the photography was in fact not necessarily created when these artists were men with long, gray beards. Am I a stickler for pointing this out? Maybe.

Let’s look at how the museum describes the exhibition (the quote can be found here):

Their personal universe and love of women were the starting points for an incessant stream of images showing the world as they saw it. All three were trained artists but entirely self-taught as photographers. This autumn, the Hague Museum of Photography is showing the work of a trio of eccentrics regarded by the photographic world as ‘outsiders’ […] The three are linked not only by their chosen themes, but also by an obstinately idiosyncratic way of life.Did you notice anything? No? Here’s the quote again, and I added some emphases:

Their personal universe and love of women were the starting points for an incessant stream of images showing the world as they saw it. All three were trained artists but entirely self-taught as photographers. This autumn, the Hague Museum of Photography is showing the work of a trio of eccentrics regarded by the photographic world as ‘outsiders’ […] The three are linked not only by their chosen themes, but also by an obstinately idiosyncratic way of life.I don’t mean to say that anything in this quote is not true. But what bothers me is the way it is presented. Let me try to explain.

First of all, I’m no big fan of buzzwords. I suppose in this day and age museums (just like commercial art galleries) have to vie for attention, and what better way than to present a compelling - and entertaining - picture? Since the cliche of the art world as a closed system, ruled by a small secretive cabal of incredibly arrogant elitists, is so convenient, it is tempting to present a photographer as an “outsider” and as “self-taught.” There’s nothing inherently wrong with all of this, but I always find it a bit lazy. So we got that here. Needless to say, the fact that someone is self-taught and/or an outsider doesn’t necessarily say anything about that person’s art.

Then, we have the image of the “eccentric.” Boy, don’t we all love eccentrics? Mind you, we don’t necessarily need to be around them - they tend to be very irritating, if not annoying in person - but seeing art made by eccentrics is always great. In fact, we demand our artists to be eccentrics, because it is so disappointing to find out that a beloved artist is just an ordinary person. Add to the “eccentric” the “incessant stream of images,” and you got a hint of madness maybe. That’s the picture of the artist as an at least borderline mad person, an image that was created many years ago, an image we love to stick to (for a fantastic study of this phenomenon read Born Under Saturn: The Character and Conduct of Artists).

So we got the self-taught outsider, whose behaviour is out of the ordinary and who might or might not be mad. Now we only have to add a sprinkle of… that’s right, women, and we’re all set. Oh, and images of women this show got. Tons of them. Right there, on the main page of this exhibition, there’s one; and she’s reduced to her behind and her legs.

But maybe I’m being a bit too critical here? I certainly don’t necessarily want to single out this particular exhibition and museum. Of course, you might point out now that that’s in fact what I’m doing, but see this as an example, maybe a particularly egregious one.

Here’s the thing. There are many reasons why an exhibition about these three artists is a very good idea. But framing it the way it is done here, while ignoring glaring problems, does not necessarily do these artists - or their audience (aka us) - a favour. It just falls short of what could be had.

For example, what really struck me was that the aspect of voyeurism was never really talked. I’m not saying that these artists were voyeurs, but when you see the photographs, it’s not very hard to come to that conclusion. In the case of Tichý it’s most obvious: A guy walking around with home-made cameras, taking photos of women without their consent, and then printing them, often tracing the shapes of their bodies with a pen. Of course, this could just be some very genius art. But it could also be some not-so-genius obsession. If it’s presented as art why then is this not discussed?

When you then add Fieret to the show, things get more complicated, because he produced photography with the women - models - being aware of it. In fact, it would not be hard to argue that unlike Tichý, Fieret actually had an eye for a good photograph. Of course, we could also argue about whether that’s true, or we could argue about whether it matters etc. But we need to argue about something here, because simply presenting the work in one big room, as the output of three eccentric men, isn’t enough.

And that’s what ended up bothering me so much: It’s certainly an interesting group of artists presented together, but I was missing a discussion of the obvious questions that one might have about these men. Of course, leaving these questions open supports the overall picture very well: They were all eccentric outsiders, two with an obsession of women (Heyboer’s case is different), better not ask any questions.

What this does, though, is to actually reinforce the very same picture that the exhibition pretends to question: None of the artists is given a chance to be revealed as someone with an unusual life, they were “regarded by the photographic world as ‘outsiders’,” and they still are. So if you leave this show thinking you just looked at the work of three creepy old men is that so surprising?