What Makes A Great Portrait? (continued)

A little while ago, I asked an assorted group of photographers and gallerists What Makes A Great Portrait? It’s one of those questions where it’s fairly straightforward to point to a portrait and say “Now this is a great portrait!” - but explaining what it actually is that makes the portrait great is quite a different story. I am infinitely fascinated by portraiture, and I decided to continue my little quest, trying to find out what made some portraits great, so I asked a different group of people the same question: “What makes a good portrait? Could you provide us with an example of a portrait that you really like - either from your or someone else’s work - and say why the portrait works so well for you?” Here is what I got back. (more; image above taken by Paul Stuart)

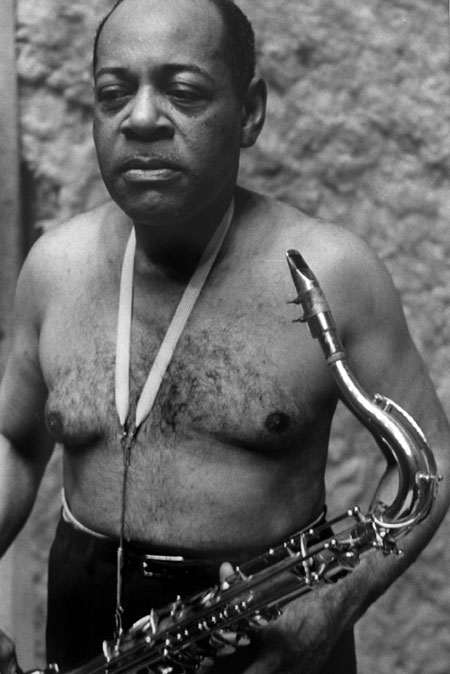

Adam Bartos: “Lee Friedlander has photographed Hawkins, who is absorbed in thought and/or sound on a hot day, from inches away. Formally, it’s a conventional portrait - in fact, Hawkins is photographed as one might a classical bust. At the same time, it’s an unconventional picture of a man usually photographed wearing a dapper suit. (see below)

“The photograph is a loose collaboration - it’s clear that the photographer and subject are comfortable with one another. But it’s not the novelty of seeing Coleman Hawkins shirtless that makes the portrait. The quality of the information the photograph presents works against its initial sensationalism. Hawkins is isolated in the picture but we know there are other people around, and that reinforces the stillness of the moment, and the concentration and grace of the man. We see how small Hawkins is, but he seems huge within the frame. His head and face are monumental, as if carved from stone, but his expression is present and expressive in a way I can’t describe. The saxophone fits perfectly his body. Friedlander sees all of this, in the instant, but there is a tenderness to Friedlander’s regard, some deep empathy, that I think makes the document of the moment transcendent.”

Adam Bartos is a photographer and music lover living in New York City.

Nelson Chan: “A portrait is one of the hardest pictures for me to take and to take well. The impulse that arises when wanting to take someone’s portrait is similar to that of high school puppy love. I’ve often compared asking to take one’s portrait to asking someone out on a first date. There’s always a sense of uncertainty that haunts your own insecurities with rejection and humility. You are fascinated by someone’s physical appearance and the immediate emotions that surge before evening connecting deeply. With a more refined sensibility as an artist, you become hyper aware of the emotional evocation someone can offer. Most of what I have described as a photographer remains the same as a viewer in what attracts me to take a portrait. But as a viewer, you are already invited to engaged with the subject. The awkward dance of collaboration while shooting isn’t present. You are asked to stare back with the power to reject if need be.

“The example I chose to include is of a picture that my brother, Jesse Chan, took with his view camera of a friend sitting in a pond close to our hometown in New Jersey. Love at first sight is what I use to gauge a great portrait and this picture was successful at that. It becomes an instant sense of fixation and draws you in to investigate the details that hide in the image. The eyes are usually flypaper and though these are not fixed on the viewer, they are no exception. You then study the person’s posture, the bluish/green water engulfing yellow/pinkish flesh, droplets beading down her shoulder, and her hair suspended on top of the water’s surface tension. It becomes a very hard photograph to look away from and transcends a very superficial feeling into a deeper emotion.”

Nelson Chan was born in New Jersey and grew up between Hong Kong and the States. Through photography, he has been exploring notions of a dual cultural upbringing between two countries by immigrant parents. He holds a BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design and is currently enrolled in the inaugural class the University of Hartford’s new International Photography MFA program.

Greg Girard: “In trying to answer this diabolical question, it perhaps deserves to be answered by asking another question: is it possible for a good portrait to be a bad photograph? Is it possible for a bad portrait to be a good photograph? If you allow that the viewer of the portrait and the subject of the portrait may have wildly different views, then the answer to both of those questions is probably ‘yes’. In discussions about ‘what makes a great portrait’ I suspect that the subject’s views are of little consequence. Much like medical doctors conferring around a supine but alert patient.

“In any case, I think I will have to side with a painter, correcting a reviewer who referred to her paintings as portraits: ‘they’re not portraits, they’re pictures of people.’”

Greg Girard is a Canadian photographer living in Shanghai; He has published two books, “Phantom Shanghai” and “City of Darkness”; a third, “In the Near Distance”, will be published in May 2010.

Michael Itkoff: “Felix Nadar, who photographed Parisian society members in the late1800s, said “the portrait I do best is of the person I know best.” Nadar’s relationship with his sitters allowed him to make compelling images that show a certain complicity of mind.

“I believe a good portrait is the result of collaboration between the photographer and the subject. If an emotional reciprocity is evident it enables the viewer, in turn, to develop a relationship with the subject. The shared moment of exchange that occurs when looking at a good portrait allows the viewer to know that which what was once ‘other.’

“I have always been compelled by Avedon’s portrait of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. The Windsors were quite used to having their photo taken, but Avedon did not want to make another generic smiling portrait. To make the picture, Avedon, knowing they were dog lovers, told the couple that his taxi had struck and killed a dog on the way to the shoot. By manipulating his subjects, Avedon was able to evoke a fleeting emotional reaction whose sincerity he captured for all time.

“Of course, a good portrait is not always based on familiarity. Sometimes a momentary rapport and its attendant ambivalence can be a subject all its own. Take this fantastic image of three farmers on the way to a dance made by August Sander.

“In the case of Joel Sternfeld’s Stranger Passing, it is the chance encounter itself that is foregrounded. Here still, the moments of reflexivity that arise between the photographer and subject create an engrossing portrait.”

Michael Itkoff is a photographer, writer and a Founding Editor of Daylight Magazine.

Anne-Celine Jaeger: “A great portrait becomes more than a two dimensional representation. It stirs up emotions. It asks more questions than it answers. It transforms into an invitation for me, the viewer, to exist with the subject in a whole new sphere or dimension. The portrait invites me to enter into the print. I’m kidnapped momentarily, from my reality into theirs, and exist or float somewhere in between.

“A portrait I come to again and again is Frank Stolle’s Sophie. It has been hanging in our living room for the last five years. The mythology created by friends and visitors around the woman in the portrait are testament to how powerful the photograph is.

“Whoever sits down on our sofa immediately start discussing: ‘Who is that girl? What is she doing? Is she rolling a joint? Is she doing a line of coke? Why is she so moody? She looks pissed off. Where is she from?’ One friend fell in love with her, having never met her, as he would fall asleep whenever he visited, looking at the woman, conjuring up stories about her.

“Only I know how the portrait came about, but it doesn’t make it any less powerful. The photograph was taken by Frank Stolle, Sophie’s boyfriend at the time, in San Sebastian in September 2000. Sophie is my oldest and best friend. We shared a flat for a month. Our mission was to study Spanish, devour Basque food and learn how to surf like the locals.

“Sophie had been working long nights in Munich setting up and managing a string of restaurants and clubs. She found it impossible to get up in the mornings and used to tell us not to address her before midday. She would sleep or read in her nocturnal den, trying to recover from months of hard work. Here, she had crept out of bed before noon, still wrapped up in the bed sheets, rings under her eyes, bed-head hair, to steal a Madeleine cake and make a cup of tea. Frank caught her deep in that ‘Don’t come into my space before I’m ready’ zone.

“‘Fuck off,’ she said.

“But that’s precisely why we want to come in. It’s that NON-invite, that mix of hostility and vulnerability, that twilight of consciousness and sleep, which draws us into the print and doesn’t let us go.”

Anne-Celine Jaeger is the author of Image Makers, Image Takers: The Essential Guide to Photography by Those in the Know, published by Thames & Hudson.

Michael Mazzeo: “A good portrait is one in which the viewer can disregard the veil of the lens, the hand of the artist and the limitations of the picture plane and enter into a dialog with the subject. A great portrait will evolve over time, allowing for new interpretations and a renewed dialog.”

Michael Paris Mazzeo is a gallerist, photographer and educator based in New York City.

Richard Renaldi: “This portrait of Liao by Shen Wei is a great portrait. It’s great because it is both revealing and mysterious. The mystery is found behind his three-quarters closed eyelids; the mattress without a bed sheet, and the minimal white walls and furniture. These elements divulge very little. The reveal is also found behind his relaxed eyelids, his nakedness, his sip, and the beautiful window light that accentuates his taut body. These qualities affirm comfort and warmth. This is a quiet, relaxed moment that Shen has captured and he has done it beautifully. Liao’s dark spikey hair stands apart so distinctly and proudly from the background, and the relationship between the subject and background is harmonious. I think despite the mystery the viewer has such a sense of the moment and the feeling in this photograph. We are given the proper balance, and our thirst, and thirst for images is metaphorically being quenched by looking at this photograph.”

Richard Renaldi is a photographer and owner and co-publisher of Charles Lane Press.

Doug Rickard: “The success of a portrait is a very subjective notion. Certainly, there are some sensibilities that we can assume to share - considerations that have been honed by time, human progression and our predecessors within the tradition of photography or art for that matter. I’ll attempt to put forth a relative truth but while I will argue for the truth of my assertions and believe them wholeheartedly, subjectivity surely never removed. So, what makes one portrait “good” and another ‘bad’? I think that one can address this question on a few different yet ultimately parallel layers. Most of these layers are visible and easy to discuss but some will remain partially hidden from view. Also, to make matters more complicated, the layers themselves shift over time and our perceptions of what is good and bad should and will change. So, I will try to focus on what I perceive to be the constant, yet also mention the changing elements.

“For clarity purposes, I want to firmly emphasize that there is an atmosphere or ‘language’ that runs through a photograph. It can be pronounced and aggressive and it can almost be absent. It speaks in a similar manner to words, such as the words that you are now reading which allow you to follow my thoughts. This photographic equivalent of written language is based on visual cues and visual statements and taps into our ability, as humans, to interpret, process and react to the information within a picture as symbols. These symbols are then ‘read’ and understood like words. But different than the written word, this visual language is unwieldy and incessantly open to an interpretation that varies for each viewer, based on the individual experience and baggage that we carry. But, within the context of this inherent inaccuracy and variation, the ‘language’ can speak with massive volume. What is lacking in accuracy and precision can be made up by the power of immediacy and complex ‘undertones’ or ‘atmosphere’. Volumes of information can be put forth and projected implicitly on a myriad of levels. The viewer is then left to consciously and unconsciously ‘understand’ and ‘feel’ their call.

“Within the context of portraiture, the slight tilt of a chin or the act of lowering the eyes, even on a scale that involves the tiniest of measurements, can dramatically alter the ‘language’ and change the scope of the information or atmosphere that pores out from the picture. Human expression and our ability to read its nuances allows one to load a portrait. We can essentially then construct and adjust expression to capitalize on this understanding. Strong portraits tap into this and manipulate this language certainly by intention and often by accident, repetition and experimentation. A ‘great’ portrait will make use of these dynamics and manipulate these undertones to provoke, evoke and stir a response in the viewer. The implications of this dynamic are then this - the portrait becomes as much about the photographer as it does the subject. In some situations, portraits can become almost solely about the photographer, the subject becoming almost a prop of sorts to do this ‘bidding’ of the creator. Todd Hido, Diane Arbus, Lisette Model, Rosalind Solomon and some of Avedon’s work - all examples in the use of undertones and language to stamp an impression of themselves and their vision on to the faces and places of subject and by extension, the viewer. The portrait then becomes an act of glorious fiction and although the subject dominates the scene, reality and real emotion become unimportant. The emotion that is important is that which exists and is created within the act of manipulation. Sometimes this manipulation can be used to mirror that of the subject, sometimes the fiction may match the reality. The important concept here is that the manipulation itself is what is driving the ‘magic’, not necessarily, the reality. In a great or ‘strong’ portrait there is never really much ‘neutral’ going on.

“It is important to note again that subjectivity does enter the equation as I don’t find the ‘neutral’ to be appealing, nor do I find the surface or the empty to be very rewarding. Obviously, some portraits can still succeed by neutrality but the examples of this are few and far between. Ultimately, if there are no undertones and if there is little manipulation of language, if there is no calculation, a portrait will fall flat and simply fail. A portrait is not about ‘capturing’ something - it is about ‘creating’ something. Even if a portrait becomes in essence, a work of massive fiction, manipulation of the language under the surface and the tapping into complex undertones is where I like to find myself going. A portrait is not about capturing reality - it is about communicating by intention and creating your reality. It is in this arena that I want to play.

“A quick note on aesthetics, the tricky and shifting element that I mentioned above. Obviously, a photograph is a two dimensional ‘object’ that is created with a set of tools and treatments. You can use a multitude of techniques to wield these tools but aesthetics or ‘style’ and our embrace of them will change over time. For example, the look and feel of portraits in one decade, the Jeff Walls or the diCorcia may look radically different from portraits in a prior decade. For example, the August Sanders or the Cartier-Bresson. And portraits now may look radically different in aesthetic to portraits of 2050. What you may despise now, you may go back to in a decade and what you love now, you may loathe in the coming years. Aesthetics are essentially like a chameleon and you can never place a definition of something great in the context of the look and feel of pixels or the grain on the surface. Also on composition, there is no constant benchmark and classic forms of harmony and balance will not stand up - for disharmony and even ‘ugliness’ can become the ‘beautiful’ and the ‘beautiful’ can become the ‘ugly’.

“Ultimately, a strong portrait cannot be summed up by style, aesthetic, expression, color, light, shadow or even pure emotion. A great portrait can only be defined by what is deeper. The success is linked to complexity of language and the manipulation of it. It is linked to the impression of the photographer, a fiction if you will, on the subject and the viewer. This access to a complex language and the intentional manipulation of the undertones should remain a constant key to greatness and contribute toward the notion of a good portrait, well beyond our immediate future.

“One final disclaimer, there are always exceptions to the ‘rules’, bank on it.

“Regards,

Doug Rickard”

Doug Rickard is a photographer and publisher. Founder of American Suburb X.

Mark Tucker: “I just happen to be rereading the “Revelations” book by Diane Arbus right now. All this thought about portraiture is flowing through me strong right now. One thing that always struck me in that book was the story and contact sheet behind “Boy with Grenade”. It’s one of my favorite images from her, ever, and I always wondered “What was the scene here? What was the situation?”, and inevitably, you always make up something in your head — some elaborate drama at an institution or something — but I guess, it’s rarely correct, no matter what photographer it is. But everyone projects their own scene over the top of a portrait they see, maybe even without realizing it. You see what you want to see. You project your own past experience. But then, there you are, and you’re reading her book, and there is the full contact sheet published, and for me, it pulled the whole rug out from underneath me. The kid looks so normal and everyday in so many of the other frames — just a normal dorky kid, (in a questionable outfit, maybe). But there’s that one frame that just transcends all the others — on a whole other level entirely, but then you realize, what you projected onto it was probably not true at all — it was probably just a normal kid, goofing off in Central Park one day. But in this one frame, he’s so much more than ‘just a kid’; he’s a threat, he’s a troublemaker; he’s scary. I just find it fascinating when there’s that one frame that just leaps out at you.

“Which brings me to a related thing that I’d like to ask other photographers reading this article — do you ever just shoot ‘when you’re not supposed to be shooting’? Purposely shooting at the wrong times? Sometimes, when I’m in clear mind, I try to do that — I shoot based on feeling of the scene, rather than ‘the person looks good right now’. And sometimes the results are fascinating. Sometimes shooting not even looking thru the viewfinder — just shoot when the feeling feels strong.

“Or, another question to photographers reading: Do you ever get the contact sheets back, and you’re doing the edit, and there’s this one cool frame, but it’s kinda different from all the others somehow, and you can’t remember shooting the picture? But you like the picture. But it’s as if you didn’t shoot it, or can’t claim credit for it. Like someone else sorta snuck up and pressed the shutter release? I love it when that happens.

“Another related topic that I find interesting is the difference in your own edit of a take, compared to another person who was not at the scene. It sorta reminds me of that story about Garry Winogrand, where he would purposely not edit a certain set of contact sheets for a good long time, in order for his own personal memories about shooting the images to go away, or be forgotten. He thought that his memories of that day, being there, talking to the people, would bias him, and not allow him to edit the take as accurately and objectively. So anyway, you get home from the job, or portrait, and you might show the take to someone else, a trusted friend, and ask them to pick their favorites, and they *always* pick the worst frames, right? Why is that? Why are they seeing something so different than what you’re seeing? And they’ll always say something like ‘I don’t know, I just love what they’re doing with their body in that frame’.

“Another thing about Contact Sheets: I remember being a kid, and I was taking this class at Maine Workshops, and Mary Ellen Mark was the teacher. And the first day after shooting, she said she wanted to only see our Contact Sheets; she did not want to see our Edit. She wanted to get inside our heads, and see how we shot, and how we thought. And obviously, she could best see that through the contact sheets. I’ve always remembered that, for some reason.

“In terms of other photographers and who I think gets close to the bone, with portraiture: Duane Michal’s early work, especially the multi-frame storytelling; Sally Mann’s early work with her children; Paolo Roversi nails it most of the time, in B/W 8x10; I saw this guy Adam Panczuk, from Poland, the other day; very strong work. Alessandra Sanguinetti goes to another level for me; Raymond Meeks does the same thing much of the time. So does Vanessa Winship. Also, the Andrea Modica “Treadwell” book was powerful, as of course the later stuff from Robert Frank, from Nova Scotia — extremely intimate and personal. I think for me, the stuff I respond to has empathy for the subject — empathy and respect.

“I don’t want to be the drunk guy in the room, badmouthing other people, but I was always concerned by some of Shelby Lee Adams’ work from Appalachia, whenever he’d drop the strobehead down below the level of the lens of the camera. I just thought it was a cheap shot, and unfair to the subject. I just think it’s a delicate line we all walk, as portrait photographers, and the tools and techniques and approaches that we use have power — power to deliver a message — a message that’s either good or bad. Respectful or not. I just think that anybody that goes putting the strobehead below the lens knows exactly what they’re doing, and they have a message that they’re trying to deliver. Enough said. Rent the documentary to see if you agree. But agree or not, you’ll realize the power of the photographer, in the way he lights, props, and directs.

“And to end, this has nothing to do with this topic, other than these are incredible portrait photographers. But this is a frame that Gideon Lewin shot, during an Alexia Brodovitch class. Talk about an All Star Class — imagine being the teacher, and you look out, and there is Diane Arbus, Hiro, and Richard Avedon as your students. Incredible.

Mark Tucker is a advertising photographer based in Nashville, TN. He specializes in portraiture and lifestyle.

Hellen van Meene: “A good portrait is a photo that you feel in your guts. You know it when you make it and you see it in the end result. the look, the chemistry, everything is on the right place.

“There is no basic trick to explain or to follow when you know that your photo will be the right one. For me, it is something that I sense it when I see the right face in front of me with good light on her, and then my stomach knows it.

“I know this sounds very vague but I don’t know how to describe it otherwise…”

Hellen van Meene is a photographer. Her most recent book is “Tout va disparaître”.

By

By