Photography, Copyright, Plagiarism, and the Internet

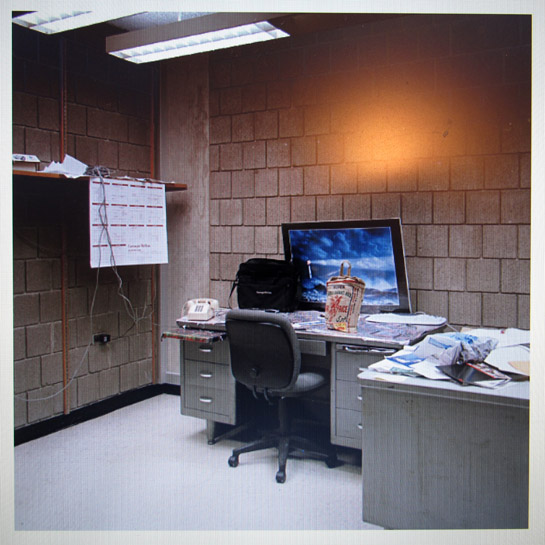

As you can see, I plagiarized myself. Or did I? I had the brilliant idea of taking a photo of one of my own photographs on the screen of my laptop, to make a statement about how photography is disseminated these days, how we view photographs mostly on screens. The photographer in me has been placated by the idea that one of his photographs is getting some exposure that it probably wouldn’t get otherwise. The art critic in me finds the concept behind that photo a bit flimsy - but then, so is Richard Prince’s behind his rephotographing of cigarette ad photography, and look where that got him. The art critic does like that extra glow in the image (that’s the ceiling lamp), though. (more)

But did I also plagiarize Prince’s original idea? Taking a photo of another photo, based on some concept? Or did I plagiarize the photographer who has already done just that - taking photos of computer screens to talk about the dissemination of photography? Note, I’m not being facetious here. You really can and maybe even should ask these questions.

Note how there also is the issue of copyright, and violating copyright is not the same as plagiarism. For example, in this particular case, along the lines well known from the Prince case you could argue that it’s not plagiarism, since the artistic idea of taking a photograph off the computer screen changes the meaning of the work. But it would still constitute a copyright violation. Since I asked myself for permission, I am not going to press any charges (plus, crafty lawyers might even make a fair-use case here).

The only thing that really is a bit of a joke here is me producing such an image, because in reality I find the concept way too flimsy to work on it. I simply needed an illustration for my post - and picking someone else’s work just didn’t feel right.

But why another big post about plagiarism? I am sick and tired of these debates, I’m sure many of this blog’s readers are as well. But the emails still come in, on a pretty regular basis, about this person copying that person, or about this ad campaign ripping off that artist. Plagiarism as an issue (or presumed issue) simply isn’t going to go away.

Actually, there are two issues, plagiarism and copyright. I recently wrote a set of blog posts about how to approach photography that was very similar to other photography; and even after looking at all the various angles I still am not 100% happy with the results. To a large extent this might be because discussions about plagiarism tend to become very toxic and amazingly unproductive.

In these debates, plagiarism is the equivalent of what people studying dynamical systems call an attractor: As the debate evolves, it will inevitably end up being around plagiarism; and once you’re in that territory, everybody’s blood pressure will be high enough as to make further debating almost pointless.

This is particularly disappointing for a variety of reasons. First, debates about similarities in the visual arts need to be had, because if a photo looks like another photo, that doesn’t automatically mean we are dealing with a case of plagiarism. In fact, I think that actual plagiarism is very, very rare (even though it does exist, of course). Second, plagiarism itself is an interesting topic. Why are we in general so upset when we discover a case of plagiarism? Isn’t that interesting that we get so upset about it? Third, plagiarism is an ethical term. It is not the same as violating someone’s copyright - copyright being a legal term. Because copyright and plagiarism are different entities, things can get pretty complicated, and it is an interesting exercise to try to pry things apart. Fourth, art itself often (but not always!) evolves through artists taking some input and transforming it into something else. Most pieces of art do not exist in a vacuum, you can tie them to other photographers, either by other photographers or by the same person. Fifth, it has been pointed out that the internet makes it much easier to detect presumed cases of plagiarism, since showing one’s photos has become so much easier; and people are visually literate enough to spot similar photos. But of course, there always is the option that both photographers worked completely independently of each other, not knowing of each other’s work. And that’s not even such a new phenomenon. For example, calculus was invented by two people at the same time (Leibniz and Newton), as were various aspects of quantum mechanics.

A little while ago, Jim Johnson wrote another post on plagiarism, in which he quoted from Richard Posner’s The Little Book of Plagiarism. Posner, a prolific writer, teaches law at the University of Chicago, and he also is a judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. I decided to buy and read the book.

The Little Book of Plagiarism is an incredibly smart book, and I can only recommend it to anyone who has an opinion about plagiarism. Since it mostly deals with text - some author copying text written by some other author - I want to highlight some of its contents; and I will try to apply it to photography, to see where this gets me.

Posner spends considerable time talking about the many different aspects of whether copying someone’s work is plagiarism or not, and there are many - very obvious - cases where it is not (read the book to see some of those cases). The summary contains the following definition, which, once you are aware of the many different details, makes a lot of sense:

“Plagiarism is a species of intellectual fraud. It consists of unauthorized copying that the copier claims (whether explicitly or implicitly, and whether deliberately or carelessly) is original to him and the claim causes the copier’s audience to behave otherwise than it would if it knew the truth.” (p. 106; my emphasis)So my quoting of these two sentences in not plagiarism because first, I do not pretend that I came up with this definition, and second, I make it very clear that I am quoting from the book. If you buy the book and open it on page 106, you will find the sentences there. My quotation also is not a copyright violation, because it is what the law (well, US law) calls “fair use.”

Of course, in the visual arts things get enormously more complicated. Not that music or words aren’t complicated enough. You could imagine that any time I copy words or some notes exactly it’s always a copyright violation and plagiarism, but that is not the case (for example, a jazz musician might insert a melody from another song into a solo). But the visual arts case is particularly complicated, because you cannot measure anything. More precisely, while it is conceivable that someone will come up with an algorithm to measure the contents of an image (for example, you could compute the two-dimensional power spectrum in the different colour channels), as far as I know nobody is doing that (I suspect there are tons of people working on this, though, because - plagiarism aside - there are tons of amazingly useful applications for something like this). So defining plagiarism in photography is more or less like defining pornography: You know it when you see it - except that what you see as plagiarism (or pornography) someone else might not agree with.

The basic problem is not only that we are dealing with an ethical problem - which usually guarantees high levels of blood pressure when people disagree. We typically can’t even agree on what exactly we disagree about! And it gets worse: Not only do we disagree about our criteria, we also disagree about how much we emphasize the different criteria!

All the various solutions to the problem somehow each leave something lacking. For example, pointing out that your child decided that, yes, two images look the same might be a nice way to put down those pesky, oh-so smug art experts, but would you accept your child’s advice when thinking about a car loan? I know it’s tempting to think that the fable of the naked emperor and the little child has real-life applications, but unfortunately, life isn’t quite so simple. At the other end of the spectrum you find those who managed to convince themselves that photography can never be plagiarized because of the nature of the medium (insert obligatory postmodern nonsense quote here).

Given all these problems and given the fact that I usually try to be pragmatic, I am tempted to think of plagiarism as something that hardly ever happens (mind you, you might already disagree with that). Genuine plagiarism in photography is rare. Of course, there are actual cases. But because plagiarism is such a toxic topic, I usually approach photography that looks very similar to other photography purely based on artistic criteria (see my first post about the subject matter). If a photographer plagiarizes another photographer, the result will just be artistically bad. Why bother with a cheap imitation? And note by “cheap imitation” I mean the artistic concept (because, after all, the copy might still be sold for a lot of money in an art gallery).

Needless to say, for the parties involved the issue has a very different dimension. If you find your own work plagiarized it’s very likely that you will not be amused. And why would you? People love to smugly comment that “imitation is the sincerest form of flattery” (which, according to the web, is a phrase coined by Charles Caleb Colton - note that you could quote the phrase without attribution without being a plagiarist! See Posner’s book for why that is the case). But it’s easy for anyone to say that who is not in that kind of situation: Discussions about plagiarism often come with an astonishing amount of moral relativism!

Posner again:

“Though there is no legal wrong named “plagiarism,” plagiarism can become the basis of a lawsuit it if infringes copyright or breaks the contract between an author and publisher.” (p. 34)But one needs to see this quote along with the following (which Jim already quoted in his blog post)

“By far the most common punishments for plagiarism outside the school setting have nothing to do with law. They are disgrace, humiliation, ostracism, and other shaming penalties imposed by public opinion on people who violate social norms whether or not they are also legal norms.” (p. 35f)So plagiarism is a serious charge, with potentially serious - social - consequences, but it’s better left outside of the court rooms. Bringing it into the court room requires rephrasing the problem as one of copyright violation, and this is where things can get very, very iffy (and expensive).

I’m not sure my claim that “genuine plagiarism in photography is rare” will convince anyone. Fair enough. It’s a claim. I see only one way to proceed, namely to think about what constitutes plagiarism. So let’s assume that photographer A creates a variant of work by photographer B. Which criteria have to be met for this to be plagiarism? Let me suggest some:

- A’s work was produced after B’s work. If A and B work on their projects at the same time, it’s unlikely it’s a case of plagiarism. Note that we could be a bit stricter and say that A’s work was produced after B began producing her/his work. It’s possible that B only has part of her/his work done; you can plagiarize unfinished projects. But this criterion needs to be considered in parallel with the next one:

- A knew of B’s work. Plagiarism is about ethics. If you don’t know that somebody is working on something you can’t commit an act of plagiarism. Knowing of someone else’s work is an essential part of plagiarism. Now it becomes clear why you can in fact plagiarize unfinished work: If B started a body of work and A saw some images and began copying the work, it’s an obvious case of plagiarism. BUT: It is usually almost impossible to prove that A really knew of B’s work. If you can’t prove that A knew of B’s work, accusing her/him of plagiarism is usually not a good idea. Even though it’s an ethical issue, unless we have proof that A knew of B’s work we have to assume that s/he did not. In dubio pro reo.

- A’s end result looks very similar to B’s, beyond simple superficial similarities, either visual or conceptual. This is obvious (again) and iffy (again). How do we define that something looks similar? As I argued earlier, the better way seems to approach the concepts or ideas behind the work. We might want to expand this as follows: The (possible) differences between A’s and B’s work are too insignificant for third parties (critics, experts) to conclude that it’s a case of normal artistic practice where one artist develops someone else’s idea/work further.

- A explicitly does not present her/his work as a parody of B’s work. Obviously, a parody is not plagiarism, even though there will be very, very strong visual similarities.

Here’s the thing. When I look at all the cases of plagiarism I can think of, all of these criteria are easily and simply met. For most cases of supposed plagiarism, however, it’s next to impossible to fulfill all the criteria. And while I’m sure that I probably missed something in my list, I don’t think that adding more criteria changes anything I just wrote, since if just one of the four criteria above is not met, it’s not plagiarism.

We have been seeing an increasing amount of accusations of plagiarism over the past few years, and it’s worthwhile to try to find out why that is the case. Many people have pointed out that since photography has become so ubiquitous on the internet, it is now much easier to find work that looks like other work (regardless of whether the two photographers in question knew of each other or not). But I am also tempted to think that the nature of the internet itself has contributed to this development.

In his book, Posner discusses how our ideas of what plagiarism is has changed significantly with time. He then writes

“As society grows more complex […] and as the spread of education and prosperity frees people from the shackles of custom, family, and authority and encourages each person to be an individual, a ‘cult of personality’ emerges. […] Individualism also creates heterogeneity of demands for expressive and intellectual products […] and the greater the demand for variety […] the greater the demand for originality.” (p. 67f)When I read this, I had a little light bulb going on in my head. The internet might just be the most extreme environment for a development like this: Extreme individuality meeting an ever increasing demand for something new (c.f. my post about our drive-by culture). Seeing images that remind us too much of other images would thus incense us because we really want to see something new online. The internet thus not only enables us to find similar images much more easily, its very nature also makes us much angrier about it than if we found the two images in two separate books, say.

Just as an aside, Posner’s description of the evolution of what we view as plagiarism, seems to provide a counter argument to Dennis Dutton’s idea that it’s evolution that guides as to reject plagiarism (c.f. The Art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure, and Human Evolution), having us prize unique displays of beauty (instead of fake ones). But when you start thinking about it, the counter argument falls apart: After all, according to Dutton humans value the genuine expression of artistic genius. In a culture like ours, taking someone else’s work and “remixing” it is often seen as plagiarism, and we get offended by it. In a culture like the one Shakespeare was embedded in, taking someone else’s work and “remixing” it was one of the most essential parts of the creation of a piece of art; so we can’t take our concept of plagiarism and simply apply it to other times (see Posner’s book for an example of Shakespeare’s practice and some background).

Given the very nature of the topic “plagiarism,” given the pointers in Posner’s book, and given the fact that the increase in the number of cases at least in part points to us really having developed a “drive-by culture,” I think it’s time to step back a little. In the context of fine-art photography, genuine plagiarism does happen occasionally, but it is rare.

Note that once you start looking at advertizing things change dramatically. You might have seen this post. There’s a lot of talk about the development of this kind of imagery - which, unfortunately, takes away from what was really happening here: The ad agency wanted the original photographer, and he turned out to be too expensive. Go figure.

Where plagiarism happens it deserves to be talked about - and especially ad agencies ripping off artists need to be exposed. But not every pairing of images that somehow look similar is a case of plagiarism. I don’t think plagiarism should be the first thing that comes to our minds. Instead, why don’t we think about what the art work tells us? If two bodies of work look very similar can we learn anything from them separately, or from whatever differences they might have?

Remember how calculus was invented - two people might actually have the same idea, at the same time, independently of each other; and with our general environments becoming ever more similar (as we can buy the same products in supermarkets that look more or less the same in places thousands of kilometers apart) shouldn’t we expect to see similar work?

By

By