Photography and Place: Appalachia

I thought it might not hurt to address the thoughts I recently outlined in Photography and Place, using a specific location as an example. Given the photographic representation of Appalachia has been very heavily discussed over the past few weeks (c.f. the Perpetuating the Visual Myth of Appalachia posts on Roger May’s blog) I figured this particular region might provide a good jump-off point. (more)

To start off, I’ll say that I don’t know much about Appalachia. However, if the map included here is to be believed, I did actually live in Appalachia for five years: Pittsburgh, PA, appears to be smack inside. I do remember locals referring to Pittsburgh as the “Paris of the Appalachia” (apparently, there’s a book), but given that I know the actual Paris rather well, this struck me as little else than being vastly hyperbolic. If you now also add the fact that I’m German, you got a very strange mix, which, however, might not be so unusual after all: Don’t we all live our lives not as being strictly this or that, but as an odd mix of all of these different things? This, of course, makes dealing with photography so bewildering, because there are all those conflicting impulses reacting to the images.

How does one go about looking at photographs from a specific region? How does one go about photographing a specific region? There seem to be two main approaches. The first was recently neatly exemplified by Pieter Hugo, who, in an interview, said:

“As an artist it’s not my responsibility to provide a responsible rendition of how the rest of the world should perceive or not perceive Africa.”And sure, that’s fine. The “I’m an artist” defense usually works, but, of course, it has tremendous pitfalls, because I don’t have to buy it. You may go about photographing Africa any which way you want. But as a viewer I will then go about putting your photographs into the context of the representation of Africa over many decades - and if your work then looks like you, as a person, might not have learned much about said representation then that reflects back to you, the artist.

The second approach can be found in Stacy Kranitz’s work. In the introduction to her Regression to the Mean, the photographer writes:

“Representing place is a complicated series of negotiations. How can the photographer demystify stereotypes, sum up experience, interpret memory and history. Regression to the mean is a term used to define a phenomenon in statistical analysis. If a variable is extreme on its first measurement, it will tend to be closer to the average on its second measurement. This concept outlines my process, which requires many visits in order to gain a photographic series of images that averages these extremes. I am initially drawn to stereotypes. Then I look to demystify these stereotypes only to find that they are rooted in some sort of reality.”This sounds very convincing, but in reality it won’t work at all. Photography is not a measurement. Photography is a creative process. By overanalyzing your own work, being overly aware of the various pitfalls (being, in other words, ultra-PC), you’re eliminating the creative part of the process, and that’s a recipe for disaster.

To stay in the realm of science, measurements contain statistical and systematic errors. You cannot avoid systematic errors - you deal with them by quantifying and living with them. As a photographer, this means that if you try to create that non-biased body of work, you must fail. It is, as I wrote before, the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

I believe the best and possibly only viable way to deal with the problem of representation is to embrace the bias. So let’s not call it bias, let’s call it what it really is: The artist’s creative vision, which is coupled to the artist’s personal integrity. That’s what it comes down to. I believe the best way to present a body of work about a place is to say: This is what this place looked like to me. I’m not showing you the place, I’m showing you my view of it. Now deal with it!

You might wonder whether this is not exactly what Pieter Hugo was saying. It is. As I said this approach has its pitfalls. I personally believe that as much as any artist can do whatever they want, they still have the personal responsibility to understand and navigate the context their work lives in. However highly you regard yourself as an artist, your work does not exist in a vacuum. It is being placed into at least the history of photography (around 170+ years), and it is also being placed into our culture, that odd, malleable thing that keeps shifting and moving. For me, this is why photography is so exciting, because once a body of work starts to exist in this environment, acting against some things and in tandem with others, the fun really starts.

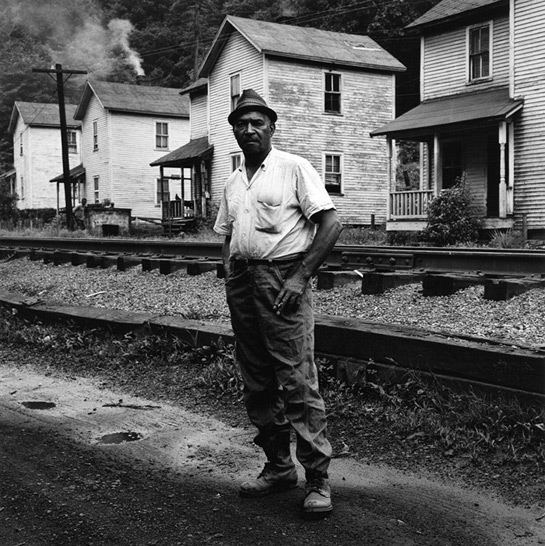

But what about Appalachia then? What does any of what I just wrote mean for Appalachia? The body of work that sprang to my mind when thinking about the region was produced by Milton Rogovin (the images in this article were kindly provided by Mark Rogovin - thank you!). In the introduction to his Appalachia series, the photographer writes:

“For years Anne and I had read about the serious problems facing miners in Appalachia. We read about the mine explosions resulting in numerous deaths. Many miners suffered from black lung disease, which the mine owners did not consider an illness caused by work in the mines and therefore not subject to worker’s compensation.I decided to quote the statement in full, because first of all, it’s a truly wonderful statement. This is how you write about your photography. Second, the statement makes things very clear: It provides the impetus for the work, and it clearly lays out the photographer’s interests.In 1962 we decided to spend out summer vacation time in the minefields of Appalachia. Most of the larger mines were cosed [sic!] at that time. The only ones functioning were small, run by a handful of miners who leased them from the big mine owners. Day after day we drove around looking for small mines, where I asked the miners if I could photograph them. Mainly I concentrated on the families who lived in the mining areas. I photographed them in their homes and on their porches, where they sat to get some relief from the stifling heat. The results of the first summer’s work were so encouraging that we returned to that area over a period of nine summers.”

What Rogovin’s statement does is to allow us to engage with his photographs and their maker. These photographs are not Appalachia, they were done there. Not more, not less. And they were done by someone with a very specific interest who also happened to be an amazing photographer. Unless we expect too much of these photographs (we could, for example, expect them to be a truthful representation of Appalachia), we can engage with these images and see how we react to them. We can then try to find out what it is that makes us react in certain ways. And lastly, we can then try to find out what these photographs might tell us about Appalachia, and the human condition, once we’ve taken the photographer’s role and our own as viewers into consideration.

Now, how do these photographs compare to other photographs taken in Appalachia? I don’t know. I don’t think there is a simple answer here. I don’t think that if we look at enough photography of Appalachia we will somehow, magically, reach the stage where we know Appalachia, where Appalachia is being “truthfully” represented.

Even if it were attainable (it is not) there is no need for such a truthful representation. What we need to do instead, is to engage with the work produced by the individual artists, and to see where that take us. This will mean that some work might fall short, for whatever reason. But even when we think that some work falls short we need to be aware of the fact that that statement contains a part of ourselves and, as such, is just as subjective as the photography we’re talking about.

All images Untitled

Appalachia series

Photography by Milton Rogovin

Courtesy Center for Creative Photography University of Arizona Foundation

www.miltonrogovin.com

By

By