emphas.is: Michael Christopher Brown - The Libyan Republic

A few weeks ago, I had a bunch of discussions with various people - including a group of students at MassArt - about photojournalism. Inevitably, the various problems (or “problems”) were brought up, and at some stage someone asked why any of that mattered. It’s a good question. But I think there is a good answer. Unlike pure art photography (whatever that might be), photojournalism is more than “just” photography. We use it to get informed. At the time of the discussions, unrest in Libya had erupted into what started to look like a civil war, and several NATO countries were urging the rest to get involved. Were we going to be in favour of that or not? At the time, news from Libya filled the news, and a large fraction of the news consisted of photographs taken by photojournalists. There now is a new pitch up on emphas.is by Michael Christopher Brown, entitled The Libyan Republic - if you want to support a photojournalist specifically working in the country, which still torn by war, check it out. (more)

“Since arriving in Libya, I have tried to understand the situation. People swap facts, predictions and rumors, but the complexity of the conflict makes it impossible to fully comprehend. Once a picture is taken or a word is written it is already old news. There seems to be no way to catch up, as the database of history is filed before it is processed. And as a result I have become more confused. But I can attest to one reality, shown in these photographs. They form a loose record of my experience during the war in Libya.

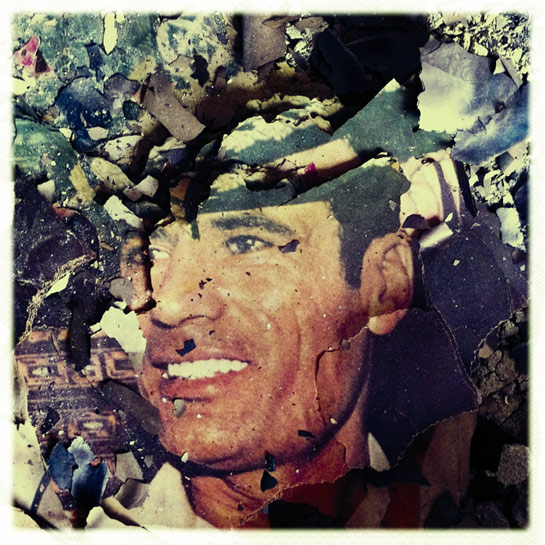

“Colonel Muammar Gaddafi ruled Libya for 42 years. During his reign, supporters were given power while those opposed saw their lives crumble. Libya changed from an optimistic, patriotic society to a people living double lives, resigning basic human rights in the face of a brutal authoritarian regime. Trust was elusive and the people were cold.

“Then everything began to change. After dictators in similar Mafia-like states of Tunisia and Egypt were forced to leave, thousands of Libyans planned their own ‘Day of Rage.’ In Benghazi, a peaceful protest on February 15th became a massacre, as protestors were fired upon by police forces. A week later, as the uprising spread across eastern Libya, young men throwing stones stormed the Katiba in Benghazi only to be slaughtered by anti-aircraft guns. Though hundreds of them were killed, with help from General Younes’ special forces the protestors took Benghazi back from Gaddafi. So began the revolution in Libya.

“Today, as the war rages on in eastern Libya and in Misrata, Libyans proudly wave the flag of King Idris, the previous ruler of the Kingdom of Libya, and carry posters of Omar Mukhtar, the leader of the resistance against Italian colonization. Libyans are treating each other as family while creating a new Libya for themselves, not Gaddafi. Though their cities are in shambles, freedom is in the air.

“The more time I spend in Libya the more questions I have. Will NATO give up? Who are the rebels and the people creating the new Libyan Republic? Who were the children affected by the HIV trial? What happened to the missing soldiers in the war with Chad and where are their families? Who were the political prisoners at Abu Salim, Benghazi and elsewhere? With your support, I will attempt to find some of these lost pieces of a past long covered up by the Gaddafi regime and continue documenting daily life, both of which have been shielded from foreign eyes for nearly half a century.” - Michael Christopher Brown

By

By