A Conversation with Vanessa Winship

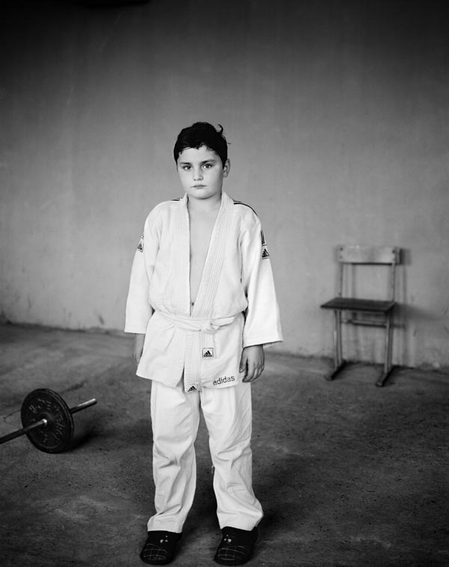

Vanessa Winship’s work came to my attention when a friend of mine showed me the copy of Sweet Nothings, a most exquisite little book of portraiture of school children in Eastern Anatolia (Turkey). A little later, Vanessa sent me a copy of the book, and we started talking about her work, so I ended up asking her for an interview. Click on the images below to see slightly larger versions.

Jörg Colberg: I usually don’t talk about technical issues all that much, but since this is almost the first thing we exchanged emails about, I might as well make an exception. You work in black and white. I’d be curious to learn about your motivation. Why not colour?

Vanessa Winship: I guess in the early days it was about how you learned to become a photographer. Processing film, and then it was almost always processing black and white, was very much part of that becoming. It was also somehow associated with truth as most newspaper ran only black and white imagery. Colour was very much the realm of the amateur, and I of course wanted to be considered the real thing! After that it was about taste, I just liked the look of black and white imagery.

For me now it means something really quite different. I am not sure any more about the premise of B and W representing truth at all; in fact the world is in colour and not b and w. So it has become a statement of, this is a photograph not reality.

My images of course are made from life and the people in them are not actors or models as such. Black and White is a wonderful tool of abstraction. It enables us to move between time and memory.

It’s interesting remembering the controversy of Martin Parr joining Magnum…. his colour work seemed so radical, could it be considered serious. It seems so absurd now.

I actually really do like a lot of colour work I’m seeing these days, although it’s not necessarily because it’s in colour, I’m more interested in the ideas behind them. The only colour work I don’t particularly like is anything overly saturated it makes me feel a bit queasy!

JC: You’re spending most of your time in places like Turkey, Georgia, and the Balkans. How did you get this focus on that part?

VW: I guess it was a process of finding a place and then just delving deeper and further. My original entry into the region was through Albania. I think it was a place that represented several things to me. First off it’s about as obscure a place as the one I am from… for certain it is nothing like where I’m from but that obscurity does resonate somewhere in my unconscious. It was also about how places like Albania could be so completely off the radar; after all it was as close as both Greece and Italy, places I had considerable knowledge of, or at least places I had an idea about. So the seeds of wondering about borders were sown.

How and who create these borders and what does it mean. I was not really in a position to go there for several years, so from a distance I began a kind of voyage of investigation. I joined the Albanian society, but was never really able to join in with what seemed like a group of tweedy intellectuals. I discovered some of its complex history and also discovered its most celebrated author, Ismail Kadare. Kadare’s work is very much about telling stories in a kind of oblique way through myths, allegories and the use of epic themes. He was able to make a commentary and critique on the system he lived in through fiction; it’s a wonderful way to discover Albania.

And finally I also knew something of the recent politics including the position of Albanians who lived in neighbouring Kosovo. I was finally in a position to go, although - as is always the case with me - I went under my own steam without any assignment and, of course, in that context without any need to work to anyone else’s agenda. After spending more than a year going back and forth to the region, because by then I was drawn in beyond the borders of Albania itself, I moved to Belgrade and then to Greece. I was developing my ideas about borders and the telling of histories.

I liked the location for this as it has a rich history of story telling both through myths and epic poetry. I decided to explore the idea of sea as the only true and natural border dividing peoples and cultures. There are of course mountains and rivers, but that was my starting point. So Istanbul seemed the obvious base. It was also a place with an incredibly rich history, and the seat of three empires. It was a city of many resonances, a perfect place for me.

JC: It seems as if written stories (or maybe writing) are very important for you, and even though I’ve noticed that for many other photographers, I’ve never seen it talked about in much detail really. You already mentioned Ismail Kadare. Are there any other writers who are important for you and if yes, in what way?

VW: It’s more a case of loving words and where they take you, rather than specific writers. I’m equally inspired by sentences I hear by chance, those words uttered by ordinary people can also be extraordinary.

I love overhearing snippets of conversations in everyday contexts; I’m probably as much of a listener as I am someone who sees.

I guess I like the combination of words and images, but not descriptive captions like the ones that accompany newspapers, rather words put together with pictures that perhaps take you somewhere unexpected, and or words that ask questions.

JC: I’m curious to learn more about your portraiture. Maybe I’ll start off with a very general question: When you take portraits what are you after? What is it about portraits that makes you take them?

VW: I think to put it most simply; it is possibly the most direct way photographically to make human contact. I can work very intimately when I work in a reportage style but my presence, and that of the viewer, is completely invisible and passive. This way of working has a place of course, but for me, when I make a portrait there can be no denying another presence, (myself and that of the viewer), and although I am not seeking for these images to be about me, (they are this too) I am very much part of the process, and as such, need to take a certain responsibility for the gaze that returns to me.

When I make a portrait I am hoping to find a moment that really expresses the emotion felt by my sitter, and sometimes it is okay if the gaze is one of uncertainty. I am looking for an expression without a mask if you like.

JC: And how do you approach your portraiture? When you walk up to your subjects, how do you explain to them what you’re doing? How do you guide them (provided you do)?

VW: It depends on the context I am working in. With the girls, for example, I visited a number of schools in the region. I explained that I was interested in the girls because for some of them going to school was the first step in acknowledging their importance in society. I wanted to extend this to the making of their image. I asked the girls to come forward in small groups either with their friends or their sisters; I knew they would feel more comfortable like this. As I was making the images there would be groups of girls standing around waiting their turn…. they almost always hang around in groups and are very physically close to one another, they are very comfortable holding hands. So when it was their turn I asked them just to stand as they had been the moment before, and to look directly into the camera lens.

In these situations I also show them something of the mechanics of the camera itself. It’s quite a funny set up at the best of times so it’s a great opportunity to engage with them beyond the image making itself. Usually this time is spent talking about who we are, simple things like the asking of a name and or talking about the clothes we are wearing… practicing little bits of English… nothing big or profound.

I try not to take too long once a person is standing in front of a camera, especially with children, too long and you’ve lost it. I almost always only make one frame of each group unless I think someone blinked and I’ll then make another one. Sometimes I would make an image of an individual girl if I felt she expressed something a bit different from her small group, and I can’t really define what that difference is or was.

I like this as an approach; I think I can only expect to ask for a fraction of seconds of themselves. I am not sure if I explain why exactly I am making the images, usually acknowledging someone’s existence is enough… I am not really someone who makes portraits of known people, they aren’t really of interest to me.

JC: Your portraiture uses what has been called the “deadpan” approach: People just stand there, with blank expressions. Isn’t that boring? And how can the viewer learn more about your subjects if their poses and facial expressions give away so little?

VW: To the contrary, I feel my portraits are probably the complete opposite of the deadpan approach. For me their expressions are anything but blank, and in fact they give everything away. The details of what they wear, how they stand in the space, and how they connect and make contact with one another and to the camera is anything but deadpan. I think the success of this work has centered in part as a reaction to this type of photography. For me the images are all about emotion, as has been all of my work.

Of course we don’t really know who they are, but if you take the time to return again and again, you begin to gather little snippets of information, the school blackboard, the landscape, the quality of their dress, their guileless demeanor, it tells me so much.

They are made in series, which at first might be considered a way of making them all the same, and after all they are all wearing the same uniform, they are all standing at the same distance etc.

But for me the very repetition actually acts as a way of really emphasizing them as individuals, but individuals unified by many things including their history, their position in society, and the fact they are little girls from a rural place.

JC: I should ask: Do you feel inspired by other portraitists, or did you arrive at your way of taking portraits on your own?

VW: I think it would be impossible not to be influenced by other image-makers, and in this case portrait photographers, (I’m happy to have photographs as my visual reference) since we are completely saturated by imagery…

I would also say that I’m probably not a typical portrait photographer because I also make images that, loosely speaking, fall into the genre of documentary, although I’m not a typical documentary photographer either, since I sometimes introduce elements of fiction in my work, it’s a question of context.

But to answer your question, I’ve recently begun to look back at early portrait photography, rediscovering Sander, discovering Mike Disfarmer (by chance), his work seems to have only just filtered through to over here, finding a wonderful series of portraits by a Greek photographer from the turn of the last century called Leonidas Papazoglou , again a chance discovery visiting the Museum of photography in Thessalonica titled Portraits from Kastoria at the time of the Macedonian Struggle, and finally the work of a Polish photographer called Stefania Gurdowa: and the book of her work, Negatives Are To Be Stored.

Having said that I don’t really set out to make a portrait after a particular style.

I hope I have something of my own in what I do, something you might call like a Vanessa Winship…

JC: My favorite series of yours is “Sweet Nothings”. Can you tell me a little bit about how you got into taking those portraits and what they mean to you?

VW: In a way I think I’ve probably answered this question in the context of the others, but in terms of what they mean to me it’s quite difficult to express. I know when I look at them they have a strong emotional impact. I see the girls in the images, but I am also reminded of other people, the girlfriend of a friend, a friend from school, a friends sister, the girl in the printing house…. I could go on.

For several weeks after I’d processed the films and started to put them together as a series they brought me close to tears…. it’s hard to articulate properly. They really are the total embodiment of innocence and that seems to be a rare thing to have had the opportunity to witness and put on film, perhaps I will never find this again.

By

By