A conversation with Steve Pyke

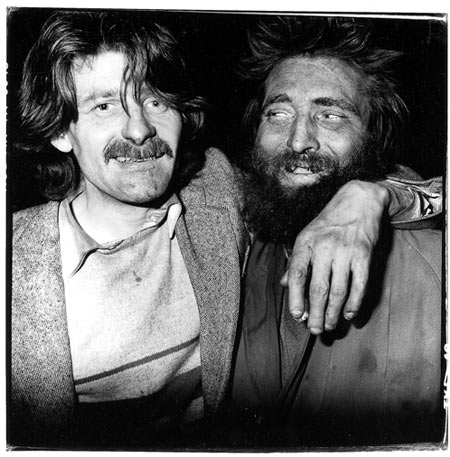

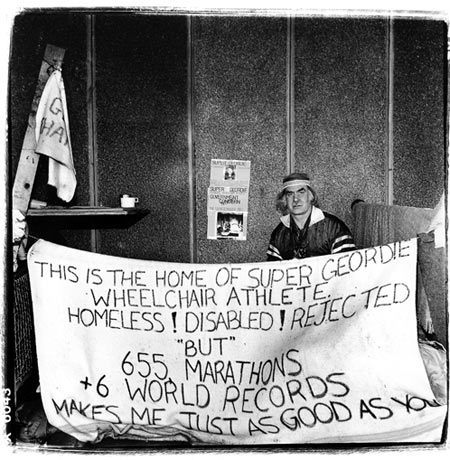

(Homeless series, London 1987)

Steve Pyke’s work is the first that made me really think about portraiture - what it does, how it works. Last year, I was invited to join a panel on portraiture, and I was extremely excited about meeting him (he was one of the other panelists) and hearing him talk about his work. I used the opportunity to ask him whether he would be available for a conversation, and much to my delight he agreed to it.

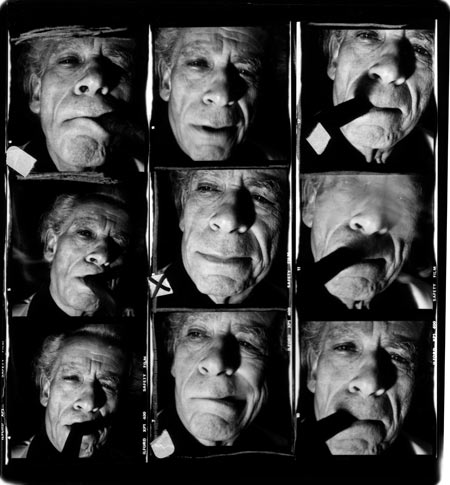

(Sam Fuller, Edinburgh 1983)

Jörg Colberg: One of the very first photography books that I bought was “Philosophers”. Back then I was still - often somewhat naively - discovering photography, or maybe I should say the kind of photography that you don’t get to see everywhere in ads or magazines, and I was surprised at how close you got to those philosophers. For many of them one would only see the face, and one can literally see everything, every pore, every hair, even the ones sticking out of noses or ears. I never thought that showing people that way was not flattering or harsh or whatever people have called that, but I’d still be curious how you came up with getting so close. How did you decide that showing faces in that way was something you wanted to do?

Steve Pyke: I like sometimes to do away with environment in portraiture. It seems to me that often it’s irrelevant, a lot of the time there’s no context between the sitter and the space I’m photographing them in. So I use seamless or black backdrops. The first time I remember working with a subject this closely was in 1983 in Edinburgh; I photographed Sam Fuller, the film director. On the way to that shoot I passed a camera shop and in the window were these Rolleinars, close-up attachments for the fixed lens Rolleiflex that I still use. I remember lighting him with an angle poise lamp and attaching these lenses. It seemed a revelation to me: that first time being able to focus so closely, the intimacy of that situation.

The human face signals our emotions, suggests our cultural background. It is the naked part, that we present to the world; our faces speak realms about our identity. Our faces anchor us to our histories, our stories and the stories of our ancestors. Our faces change with time, our faces absorb the passage of time. We tell our stories through our faces: how we present ourselves, how we use this personal canvas to convey not only our emotions, but also histories and identities.

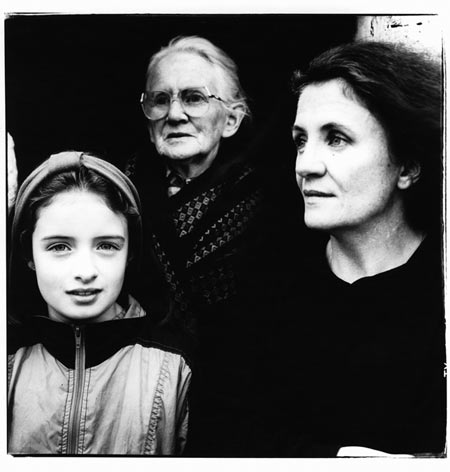

(Three Generations, Inishmaan, Aran Islands, 1991)

JC: We’re used to seeing faces, at least in print or on the TV screen, not in their original form, but “made up”, with lots of their properties concealed or hidden. It sounds with your approach to portraiture you’re trying to get closer to the “true” face of a person?!

SP: I’m not sure that describing a true face gets us anywhere, there isn’t such a thing… We present many faces to people every day, the most a portrait photographer can hope for is to make a portrait that reflects where the sitter is with the photographer.

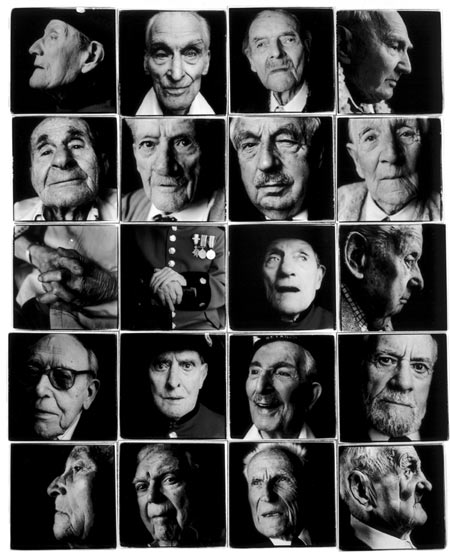

JC: And were you not worried about the kinds of accusations Richard Avedon, for example, had to deal with, namely showing people in a bad light? Maybe with philosophers you could get away with it (after all, they’re “eggheads”), but I could imagine people might have objected to subjecting World War I veterans to the same treatment?

SP: I don’t ever approach a sitting to put anybody in a good or a bad light. Even the sessions I have made with despots and mass murderers I wouldn’t seek to portray them in a bad light… It seems cheap and too easy to do. I don’t really feel that the portrait sitting is about subjecting anyone of my subjects to a bad experience. Its a shared experience.

(Augusto Pinochet, London 1998)

JC: “Too easy to do” is an interesting way to look at this - it sounds like you’re very open to what might happen. But it can’t be easy to portray a despot or mass murderer, can it? How easy is it for you to detach yourself from what you know about the person when you go to take their photo?

SP: This is an interesting question… When I went to photograph General Pinochet from Chile for the New Yorker I was worried that he might try and shake my hand. I didn’t want to do this. I was too aware of the crimes he had perpetrated. A friend of mine form Chile who I knew in the seventies had lost his father and brother. I was told he would barely acknowledge me. When he walked into the room the first thing he did was to reach out his hand to shake mine. Of course we shook hands, but I was very uncomfortable. The reason I was there in that room was to make a portrait of him, to communicate something of the person who stood in front of me. Most of the images I made that day were of Pinochet looking like an old man, someone’s granddad, which of course he was. But the image I ultimately we chose did not portray him as a warm old granddad figure…. that, it seems to me, would have been irresponsible - given his crimes.

JC: Have people complained, maybe saying “Hey, that’s not me!” or “Why did you make me look so ugly?” or whatever else someone might say?

SP: I have received requests not to reproduce certain images for all sorts of different reasons. What we see when we look at our reflection in a mirror and when we look at a photograph are often two very different images.

I once photographed the French philosopher Helen Cixous. She was so worried about the results, which I sent to her, that she wrote to me and said that to reproduce these images was to her tantamount to rape. I still have the letter. It seems to me that if you have any sense of social responsibility in a case like this then you withdraw the session - and this is what I did.

JC: Recently, I dug out my Rolleiflex, and I put a close-up lens on it to see what it would be like to take portraits like that. I noticed that with the second strongest lens - which makes the face fill the entire image - you have to get very close to the person sitting for a portrait. I had a friend try it on me, and the camera was right in my face. So with “Philosophers” (and the other portraits done in that style) you must have done the same or at least something very similar. Portraiture itself, taking someone’s photograph, already is such such a delicate matter (or maybe it isn’t?), but getting so physically close seems to add yet another twist to it. How have people reacted to this? Has this made taking portrait harder? Or easier?

SP: I can only count three or four situations in nearly thirty years of photography, where people reacted badly to me being so close to them. The physical space I inhabit with people has always been interesting. There’s a reason I like to work in this space, it is very intimate, but on the whole people react well to it. Sometimes, they show amusement, which may be a foil. It’s the space where usually we only allow loved ones. It’s a place to respect.

(Veterans, 1993, various locations)

JC: How do you get so close then, especially with, as you said, people not being used to strangers getting this close?

SP: I think I’m open in conversation with people, which is where we meet each other… I often start the portrait session close it’s just rare for anyone to recoil or deny access.

JC: I remember Alec Soth saying that part of the thrill of taking a portrait with a view camera is that one can really stare at a person’s face without being seen - while focusing under the hood. That’s almost like the other extreme to taking a Rolleiflex portrait with a close-up lens. I’m wondering whether and how maybe the photographers’ personalities have something to do with all of this. When you see portraits, there are superficial differences (resulting from camera types or other technical aspects), but there also is that je ne sais quoi that makes a portrait taken by you look like a real Steve Pyke portrait (and not an Alec Soth one, for example). How does the photographer’s personality enter into the portraiture?

SP: I rarely look into the ground glass of my camera except to momentarily check composition. I engage my sitters, we speak for far more time than I photograph. At certain points in our conversation I will photograph . It must be instinctual by now, but also I hope it creates spontaneity. Most of my frames are made looking at and interacting with my sitters.

(Homeless series, London 1987)

JC: For your project “London Homeless” you actually went to live with homeless people. Can you tell me a little about how you got into the project?

SP: To put this work into a context: the Homeless crisis in Britain during the mid 1980’s was awful. It was so in your face, especially on London’s streets. I remember being at a concert at the Royal Festival Hall on the South Bank. Underneath the venue was a car park, and when the Mercedes and BMW cars pulled away, behind them were the homeless, sheltering in cardboard boxes. The disparity between those that had and those that didn’t in Thatcher’s Britain of the 1980’s seemed vast to me (I think it’s worse now). I decided to start photographing portraits in Cardboard City. It became clear very early on that I had to spend a lot of time getting to know the people there. For the first few weeks I didn’t photograph, which at times was frustrating. But I felt they needed to get to know me and a more intimate atmosphere would evolve. After a while I began to make images but always in a formal direct way. This could be complicated at times but I felt the portraits showed the dignity of my sitters and were in no way exploitative. Of course, not everybody felt that at the time about them. I would worry about exchange and from the beginning would return each morning to the darkroom to develop the rolls, then would quickly make prints that I would return to the sitters the next evening. The community changed so quickly, from night to night sometimes, that it became easy to miss people. In some of the later portraits you can see earlier prints on the wall behind the sitters. Making this work but knowing that I had the choice to return to a warm bed was confusing and made the experience harder. I remember feeling at one point that I had had enough and didn’t want to make anymore for a while. The people whose reaction I was really interested in were the homeless of Cardboard City. They saw the work, and on the whole their reaction was extremely positive. They wanted more public attention brought to this situation.

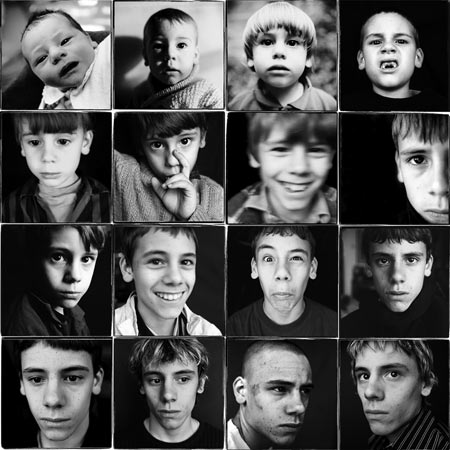

(Steve Pyke’s son Jack, 1988-2008)

JC: So then the big question: Who determines the outcome of a portrait session? The photographer? The subject? And what role does the viewer play (if any)?

SP: I have always been uncomfortable with the phrase “taking pictures”… I think it’s all wrong. Mostly I think there is an understanding that takes place during a portrait session between the photographer and the subject… For us both it’s more about an exchange… giving rather than taking. My portraits are the result of conversation between two or sometimes more people. This conversation is bound to have impact upon the portrait.

(Steve’s new book, Earthward, is available from Nazraeli Press)

By

By