A Conversation with Roger Ballen

A photo by Roger Ballen is not something that you look at and then forget. His photography possesses a very intense beauty. I was recently given the opportunity to speak with Roger about his work and its background.

Jörg Colberg: Looking at the different series of work that you’ve done there appears to be a development towards the abstract as you move from portraiture (“Platteland”) to people who are increasingly part of a surreal setting (“Outland” and then “Shadow Chamber”) to your new work, which is much closer to paintings than to photography. What caused this evolution?

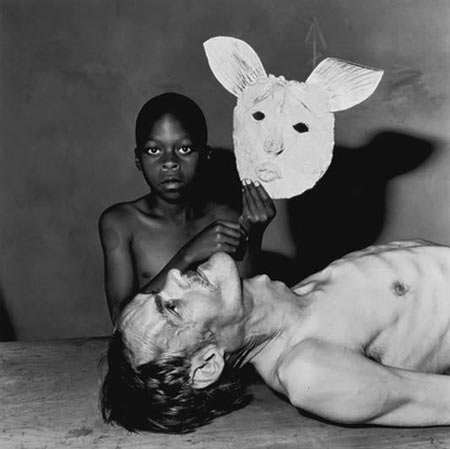

Roger Ballen: The change from being a documentary based photographer to an artist was a gradual process that occurred over quite a long period of years. To the best of my knowledge sometime around 1997-98 I started to feel that the purpose of my photography was primarily to explore my own interior rather that the South African culture I was living in.

During 2003 the nature of my work started to change dramatically. I started to deliberately avoid including the faces of my subjects in my photographs as I felt there were other aspects of my images that could not come to the forefront as long as direct human presence existed in the images.

JC: What are these aspects that you would like to show?

RB: The formal qualities of my photographs have always been crucial to the overall meaning of my images. On many occasions I have mentioned ‘that the forms in my images create the content.’ When ones refers to form in my images it comprises a whole host of variables such as texture, tone, lines, shapes, all of which interact in organic fashion to create a layered, complex meaning. Most importantly, the forms must be clear and to the point; but it is my hope that the end result of composing these relationships is to create an essence of ambiguity.

JC: I would like to talk to you a little bit about your portrait work, especially the portraits from “Platteland”, since many of my past conversations have at least brushed this subject matter; and I personally find portraits infinitely intriguing. Can you tell me a little bit about the series, in particular how you decided whose portrait to take? I read on your website that you said you weren’t prepared for the controversy that the series created. What was it about the controversy that surprised you, and in retrospect would you do anything different if you were to shoot that series again?

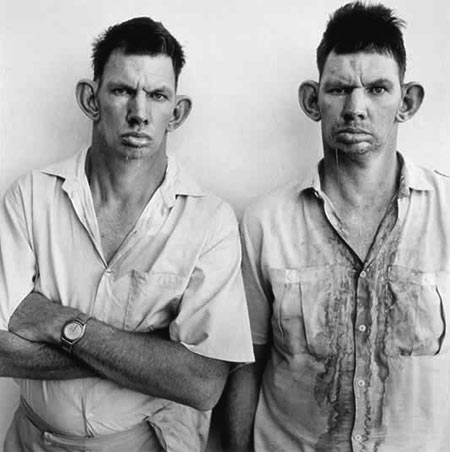

RB: The book Platteland, Images from Rural South Africa published in 1994 depicted a marginalized, isolated group of white people that habituated the South African countryside. The photographs were taken during a period of political upheaval in South Africa and the book attracted world attention as it was a real revelation to many individuals inside and outside of South Africa that many Whites were poor and alienated.

I have never taken photographs for ‘the market’ and consequently would not change any aspect of what I created in this series. Up to this time photography was purely a hobby; I earned my living as a geologist, and having never really spoken about my work I was forced to defend my intentions which I was fundamentally unprepared for.

The issue of why one chooses to photograph a particular individual over another individual is a very complex issue one I find difficult to answer. Ultimately the choice involves a whole host of subconscious and conscious decisions. It is almost as problematic as the question of why one colour or taste is more appealing than another.

JC: What do you think was the effect of showing that there was indeed a large number of poor white people in South Africa? Especially what did it achieve inside South Africa?

RB: It is very difficult to know what these images ultimately achieved; but for some reason many of these images have become icons in and outside of South Africa. One of my more important goals as an artist is to change or expand human consciousness hopefully in a positive way. The fact that so many people know my images means that they have been affected in some way.

JC: What do you think is needed to take a good portrait? What kind of interaction is needed for that? And who, the photographer or the sitter (or both?) ultimately is the key person?

RB: I believe the process that is required for every photograph is different; and the fact that one must continually improvise to the particular circumstances is crucial. Ultimately if one is to create a significant impact as an artist the work must reflect one’s vision and style. Consequently then the key person is the artist; I sincerely believe that it is virtually impossible for anybody to create an identical essence to that pervading most of my images.

JC: So then to make sure that the photo reflects you vision and style how do you influence your sitters? I realize that ultimately, this might be a very hard question to answer, but I also know that there is wide-spread interest amongst photo enthusiasts about this. The question “How did he (or she) do this?” might be the one that I most commonly see in emails. To what extent is this whole process something that happens unconsciously?

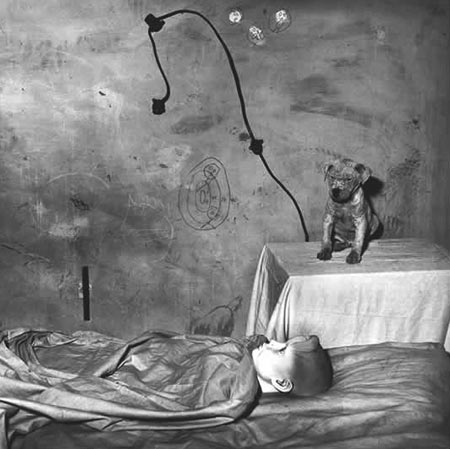

RB: It is important to note that most of my photographs over the past few years do not contain people. Animals, objects, and drawings are far more prevalent then a direct human presence.

I believe there are literally thousand of conscious and subconscious decisions that assist in the construction and culmination of one of my photographs. Consequently there is hardly the slightest possibility that someone photographing a similar subject in an identical environment will be able to create a photograph with an essence that is aligned to mine.

Ultimately each photograph requires a different approach; to the best of my understanding the process is dominated by my imagination.

JC: You have a background as a geologist, and you live in South Africa, which is somewhat remote from the world’s big photography scenes. So you started out as an outsider, maybe with a somewhat different artistic sensitivity. Is this something that you were ever aware of, and if yes, did you see it as a strength or a weakness? And who were your main influences as an artist?

RB: It is impossible to surmise what would have happened to ones’ life in another situation. Nevertheless, thinking back over the past twenty-five years the isolation that I experienced living in South Africa forced me to look ‘inward’ rather than than seek answers from others work. I have always believed that the most important source of inspiration should come from the process of understanding one’s existence. I have been very fortunate as photography has allowed me to delve into my interior and externalize it.

My main influences as an artist over the past decade has ultimately been nature and the deeper aspects of my own psyche. I could name a whole host of people such as Bacon, Picasso, Dubuffet, African Art that have effected me on some level.

JC: If you had to pick one photo to take along onto a deserted island, which one would that be and why?

RB: Unfortunately I am not able to answer this question as each important photography conveys some important part of me.

The paperback version of Shadow Chamber is due to appear this month. This conversation was commissioned by American Photo and can also be found here.

By

By