A Conversation with Rob Hornstra

I have been thinking about book publishing a lot these past few months, and when I looked through Rob Hornstra’s website I found not only a lot of very interesting photography but also a whole set of self-published books, most of them sold out. I got in touch with Rob and he agreed to sharing some of his “secrets”.

Jörg Colberg: You’ve published quite a few books, and as far as I can tell, they’re all self-published, but not using so-called printing “on-demand” (POD) but actual, “old-fashioned” book publishing. What is you basic motivation behind this?

Rob Hornstra: There is not really a good reason for this. I have the feeling that I have the largest amount of control in old-fashioned book publishing. And, by the way, I don’t think POD is cheaper when you have a print run of 1,000 copies.

JC: Doesn’t this kind of self-publishing add a lot of work to your already busy schedule as a photographer?

RH: I don’t view self-publishing as extra work. It is a part of my work and actually one of the parts, which I like the most. I don’t see myself as a photographer in a way that I am always carrying a camera or that I always need to make pictures. I never make pictures, only when I am working on a documentary. Actually, I think when asked for my occupation I should answer that I am not a photographer, but a documentary maker. In this profession you need to do lots of things: Organizing money, a lot of self-study, of course making photos, publishing books, writing articles etc etc. Making photos is only a small part of the job.

Maybe I should explain that I don’t see a book as a mass product. For me, a book publication ultimately is the best way to present my projects, better than exhibitions or anything else. So the book actually IS my project. I try to avoid every distraction, which might divert you from the project. So there are no articles or biographies about me, written by so-called important curators or whoever. No introduction about the project, written by a local journalist or an activist. I am even happy that there is no bar code on the book. I only use a colophon on the flyleaf. By the way, if you compare it with a documentary film: I’ve never seen the biography of the makers before the film starts.

I think it wouldn’t make me happier to see my book on Amazon. For me, it would feel a little bit like selling my photos through IKEA. Why should your book become a mass product? I just want to make the best documentary photo books that I can, without any restriction to keep production costs low or whatever you need to take care of in order to produce a mass product. It is most important that the book exists and that it is exactly what I want. If it sells out quickly I can always decide to do a reprint. Or not.

JC: This all makes you somewhat unusual, though, doesn’t it? Most photographers would consider self-publishing a tremendous amount of work, and I don’t think they would necessarily define a book as the final product. When you talk to other photographers or to people dealing with photo books what reactions do you run into?

RH: I think there are probably more photographers than you think who would define a book as the final product. But I agree that people are sometimes a little bit surprised about my ‘unusual’ way of working. At the same time, I am surprised that so many photographers have such extremely conservative ideas about how to produce a book. And to be honest, I am also surprised by the big number of conservative designs and the often conservative ideas of what should be the content of a photo book.

JC: I don’t know how much of this kind of information you are happy to share, but with an edition of 1,000 copies (as in the case of your new book “101 Billionaires”) there must be quite steep costs associated with self-publishing. How do you go about this? What would you tell another photographer who is interested in the same kind of self-publishing and who does not have the funds upfront to get 1,000 books published right away?

RH: You don’t have to start with a print run of 1,000 books. My first book ‘Communism & Cowgirls’ had a print run of 250 copies and cost me 7,500 euro. As a student I couldn’t apply for any funds, and it seemed impossible for me to find a publisher who would be interested in spending his money on a graduate. I started a pre-sale, made a flyer, and I told everybody that I had to sell 100 books (30 euro each) in advance to make it possible to print the book. It happened within a month, with a little help from my family, friends, colleagues, classmates, friends of friends and so on. After the release the book ‘Communism & Cowgirls’ sold out within a few months. So I had my money back. Of course there is a risk in this way of self publishing and the higher your print run, the higher the risks you take.

I described the process in an article for Witness Magazine:

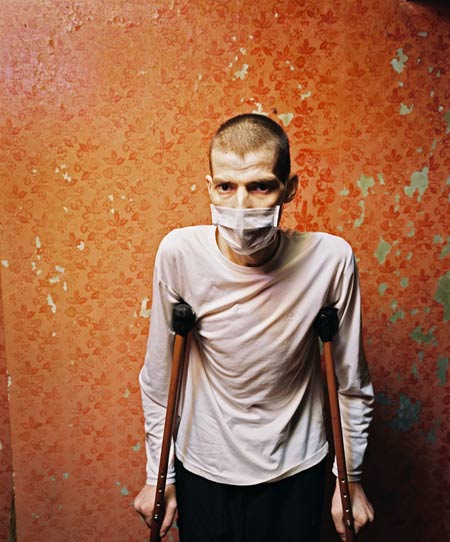

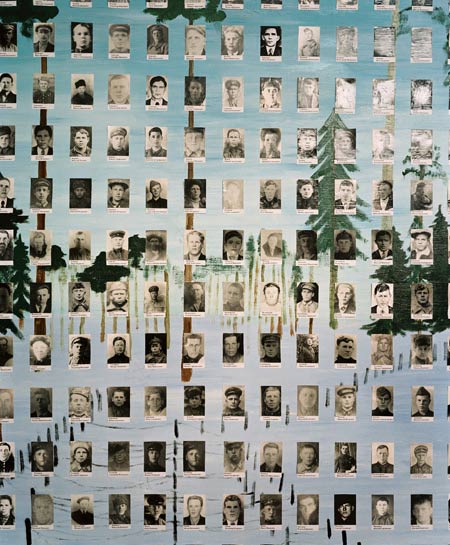

“For my graduation of the Academy of Arts in Utrecht in 2004, I went to Russia to make a documentary about the first generation of Russians growing up after the fall of communism. After I came back I knew one thing for sure: This project had to be presented in a book. I took a course in bookbinding, and thought that with the latest techniques for printing, it had to be possible to produce a few ‘real’ looking photo books which I could present at my graduation.

“After making a rough selection of images, I immediately started designing the book, which was a complete disaster. There were too many options for me and I felt completely lost. Coincidentally, I met two talented designers who had just started their own agency. They decided to design my book as a non-profit prestige project. And they took it seriously. Night after night we kept on working while discussing the progress. More and more I felt that this project was becoming too big just to end up in only in a few handcrafted books.

“Approximately three months before my graduation, I started to contact some printers about the costs of printing a paperback version in an edition of 250 copies. I was shocked. It would cost me at least a few thousand euros. More than I had ever seen on my bank account. As a student I couldn’t apply for any funds, and it seemed impossible for me to find a publisher who would be interested in spending his money on a graduate.

“In checking to see if there was any interest in my book, I told a colleague bartender about my plans of producing a photo book called ‘Communism & Cowgirls’. He immediately bought a copy in advance. Within the next few minutes I sold four books, and I started to make a list of numbers in my agenda. To promote the pre-sale I made a flyer, and I told everybody that I had to sell 100 books in advance to make it possible to print the book. It happened within a month, with a little help from my family, friends, colleagues, classmates, friends of friends and so on.

“This piece of luck gave me confidence, and I started to investigate new possibilities. I wanted to have a sewn hardback version, and the designers preferred a fold-out page in the middle of the book. The book became more expensive, but producing the book in Eastern Europe would save me some money. I decided to order the book in a edition of 250 copies, which would cost me over 7,500 Euros, so the sales price had to be 30.00 Euros a copy to even out the costs. Nobody would ever get a book for free. After signing the contract, I couldn’t sleep for a week, only thinking about book stacks in my room which could not be sold and debts in my bank account.

“In spite of the designers’ resistance, I wanted a list with numbers and names of the first hundred buyers in the back of the book. The designers claimed that the list didn’t add anything to the story. I convinced them by saying that the book wouldn’t exist without these people, so they were in a way responsible for the story. Three days before my graduation, the book ‘Communism & Cowgirls’ was created with a list of numbers and names, and sold out within a few months.

“After starting the pre-sale of my second book, ‘Roots of the Rúntur’, the list of numbers turned out to be successful. Within three days, the numbered edition 1-100 was sold out, and people who didn’t check their email regularly reacted incensedly not being on the list. Instead of being a necessity, the list of numbers turned out to be a great marketing trick. ‘Roots of the Rúntur’ - published in a circulation of 500 - also sold out.

“I am working on a new book project (travelling all the countries of the former Soviet Union) and hope to publish a new book at the end of 2008. I am not looking for publishers anymore; publishing yourself is much more fun, and the Internet offers great distribution opportunities. Nowadays, it’s quite common that people ask for information how to get ‘on the list’ or ‘what to do to get number one’. I always answer to sign in for my newsletter and just wait in front of your computer screen. Or do an unfair proposal. If it’s about numbers, then I am prepared to be corruptible.”

JC: I’m sure many people are not aware of this, but when self-publishing a book, a very large part of the actual effort is to then sell the book. How do you go about this? Do you work with distributors? How do you sell 1,000 books? Do you have 1,000 friends?

RH: I don’t work with publishers or distributors. They need money for the work they do, and I think I know better places for my money. Besides, I have a healthy distrust for this kind of business. Of course there are good publishers and bad ones, but even the good ones need to earn money with my book.

My upcoming book ‘101 Billionaires’ has 16 fold-out-pages. That’s extremely expensive to produce. I don’t believe there is a single publisher in the world who would agree with 16 fold-out pages, because it makes the retail price sky high. As an outsider (the buyer of the book) you don’t really see this. So it doesn’t have marketing reasons. But for me these fold outs are important. Someone told me recently that the retail price of a book should be at least 4 times production costs. That means that the retail price of ‘101 Billionaires’ would be 140 Euros! That’s one of the reasons is that I don’t work with distributors or publishers. Of course, my retail price is much lower.

Apart from all of this, I think it is an illusion to think that you sell many more books when your book is distributed in all kind of shops. The market for photo books is extremely small, and 95% of all photo book buyers know the way to only a few specialized book shops in the world (often on the internet), for example Shashin or Schaden. So if you sell your book through these shops you already reach a major part of your public.

Of course, it remains to be seen whether I will sell 1,000 books, because the book is not even released, yet. So far, I sold 300 copies (during the pre-sale). You never know, but I have the feeling that the book will sell out rather quickly.

I think the reason for this is a combination of many things. I am not the one who will judge the quality of my work. What I have seen since my graduation (2004) is that the interest for my work is slowly but steadily increasing. At first, I only had a audience (and exhibitions) in the Netherlands; then it started in Germany and Austria and the rest of Europe, and this year I have witnessed interest from the US as well. During the pre-sale of ‘101 Billionaires’ I sold books in fifteen different countries. Of course, I work hard on this with an up-to-date website, regular newsletters and publications in magazines and on the internet. But maybe it has something to do with the fact that I am doing everything in my own way? I am not sure about that. Maybe you should ask the buyers of my books why they buy them.

JC: You’re also a (the?) driving force behind FOTODOK, “an exhibition space in which documentary photography can be presented in an accessible manner to a broad public, without sacrificing any of the essential depth.” In this description, I see a few interesting ideas, the most important one might be that presenting documentary photography might risk what you call “sacrificing […] the essential depth”. Can you elaborate a bit on this and on what’s behind FOTODOK?

RH: People are reading less newspapers and magazines and, because of that, less articles about difficult or far away subjects. Many people are only watching crap on television, or they read gossip magazines. I believe that if you know more about different people, different regions, different countries, different cultures that your consciousness will be higher and your prejudices towards others will be lower, which will lead to a better world.

You can read books or articles about other cultures, countries, etc., but if most of the people don’t want to do that anymore you should find a substitute for this; and I believe that in many cases documentary photography can be a very good substitute. Many people like photos and are rather look at a photo essay instead of reading a complicated article. In the past few years, I saw so many very interesting documentaries, and I thought “Hey, people should see this!”. That became the start of FOTODOK. It is all low profile but high quality: Exhibitions in any suitable form, but also debates, lectures, education; and we have many more ideas for the future. It is a very energetic group of young people.

JC: And then of course, there’s your own photography, a lot of which has taken you to the former Soviet Union. How do you go about finding project that interest you and how do you then prepare for them?

RH: The former Soviet Union became interesting for me from the moment that I started to realize that I don’t believe in capitalistic societies. I am happy that I am finally finding evidence for this, but that is another issue. Although I am definitely not a Communist, I started to get interested in Communist societies, and in particular Russia was changing very quickly from Communism to Capitalism in the most extreme form. I believe transition periods are photographically always interesting. Besides, I love Vodka and fat dinners. And I am fascinated by the flexible but self-destructive soul of Russian people.

I think preparing for a project for me is the same as for every other documentary maker. Just read as much as you can, talk with as many people interesting for your project as you can, watch films and photos, read papers etc. Since I am especially interested in the common people I also had to learn Russian to get closer to people. That was the hardest part.

JC: There recently has been a bit of a discussion about the intersection of documentary photography, photojournalism, and fine-art photography. While it doesn’t seem to matter what you want to call something I think adding a label makes people view the work in a certain way. For example, photojournalism is seen as, well, journalism (so it has to be true), whereas fine-art photography is seen as art (so it isn’t necessarily true). I was wondering what your thoughts about this complex are.

RH: The following comes from the FOTODOK website, but actually these are more or less my words: “Documentary photography is the use of images to tell a story based on real events, from the perspective of the photographer. Documentary photography bridges the gap between photojournalism and independent art photography.”

I believe that documentary photography is a form of art. Just like ‘autonomous photography’ (I don’t know how you call this in English). By the way, there are many overlaps between these forms. Somebody wrote that one of the most general explanations of art is that art is an expression of the human soul. That is exactly what documentary photography is. Otherwise it is not documentary.

I believe photojournalism is something else. Not better or worse or more difficult or easier or whatever. I do not believe that journalism is independent (you know everything about that in the US), but I believe that the goal of the photojournalist should be to focus objectively on what is happening at a certain moment and not what his/her opinion is about it. That stands in contrast with making a documentary where the most essential part is your opinion. However, I realize that being independent for journalists is almost impossible. I think inside every journalists there hides a (small or big) documentary maker.

By

By