A Conversation with Richard Mosse

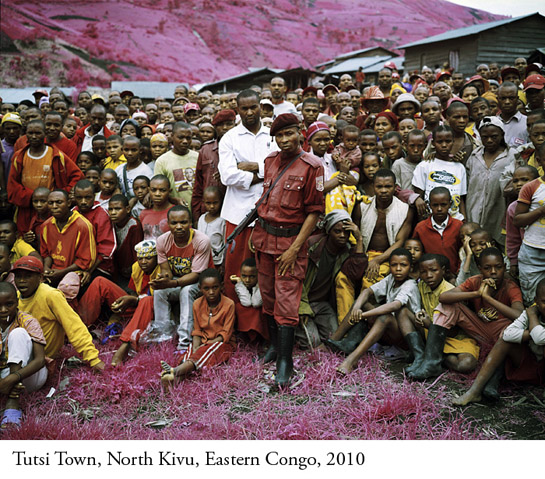

By now you’ve probably seen Richard Mosse’s Infra, photography of what we tend to casually refer to as the conflict in Congo. Why was he using those strange colours? I asked him. (more)

Jörg Colberg: Let me start off by asking why/how you decided to take photographs of Eastern Congo? How did your interest in the region develop?

Richard Mosse: Congo is regarded as one of the first places in which photography became a powerful humanitarian force. Around the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, there was a watershed of concern surrounding the Belgian monarch, King Leopold II’s personal abuse of power in the region. This was simultaneous with the rise of photography within mass media. Two English missionaries, Alice Seeley and John Harris, left for the Congo Free State in 1896 and photographed the brutal human rights violations that they witnessed there. This and other portrayals of the region’s horrors eventually brought an end to Leopold’s claim to Congo. But the misery continued.

Also at work at this time was Joseph Conrad, a steamboat captain along the mighty Congo River in the early 1890s. Conrad wrote a short novel about his experience, Heart of Darkness. I find the book disturbing and have been haunted by certain images from the narrative which are portrayed in a keenly cinematic style. I still wish to remake some of these scenes as video pieces. Conrad’s chaotic and fragmented sensory description of a situation is very close to how we see - how our eye darts and stops repetitively across a scene. It’s very close to photography itself, and especially the moving image.

Heart of Darkness has borne an extraordinary cultural influence. To this day, Congo seems caught in the wake of Conrad’s steamboat. In the western popular imagination, the place is often regarded as touched by madness, darkness and cannibalism. The conflict’s recent disturbing turn towards gang rape and sexual terror, exacerbated by the United Nation’s ineffective and convoluted bureaucracy, only adds to the region’s reputation as Breughelesque and incomprehensible, echoing Mistah Kurtz’s the horror, the horror.

Wandering through the Menil Collection in Houston I was fascinated by Congolese statues that had been studded with metal nails fashioned in waves. Looking at them, I remembered that the slaves on Conrad’s steamboat had been paid in rivets - a kind of placebo currency invented by the Belgians. Here before me, I realised, were complex and challenging aesthetic forms made from these useless iron slivers. I checked the date and it tallied with Conrad’s visit to the Congo Free State. Here was ‘primitive’ aesthetic virtuosity, exceptional works of art produced in the midst of a humanitarian catastrophe, made by its victims out of the pathetic and worthless tokens paid out by their brutal oppressors. I could wait no longer.

JC: I’m curious about your choice of medium, using Kodak’s Aerochrome infrared film, which, according to the company’s website “is intended for various aerial photographic applications, such as vegetation and forestry surveys, hydrology, and earth resources monitoring where infrared discriminations may yield practical results.” Essentially, plants start looking pink, and other colours shift as well, resulting in what one could call a bubblegum palette. Is a bubblegum palette a good choice for a rather complicated situation, about which most Westerners know very little?

RM: Mark Twain’s 1905 political satire King Leopold’s Soliloquy portrays the Belgian king’s defense against the contemporary tide of human rights activism in the Congo Free State. ‘The Kodak’ it reads, ‘has been a sore calamity to us.’ More than a century later, I wanted to bring ‘the Kodak’ back to the Congo. But I also wanted to bring the Kodak to bear on the Kodak. I wanted to examine the medium itself.

Kodak Aerochrome was developed during the Cold War in conjunction with the US military. Flying at altitude with a nosemounted aerial camera, this film was able to cut through the ultraviolet haze, reading the infrared light spectrum bounced off the earth below. Chlorophyll in the landscape’s foliage reflects infrared light, which is invisible to the human eye. Meanwhile, the earth and other contours absorb it. The green camouflage netting above hidden enemy sites absorbs infrared light while the surrounding vegetation bounces it directly back into the sky. In this way, the film technology was used to reveal an enemy’s location. By reading the landscape’s heat, the military had a way to perceive its hidden enemy.

Over time, the Aerochrome technology became accessible to civilians, and was useful to farmers, hydrologists, geographers, cartographers, archaeologists - to anyone studying the landscape.

While I was in the Congo in early 2010 Kodak announced the discontinuation of the stock. Defence technologists now work in digital hyperspectral technologies. The false-colour Aerochrome was a thing of the past. I was dealing with an abandoned technology which I wanted to use reflexively, to work this military technology against itself in the hopes of revealing something about how photography represents a place like Congo, a place so deeply buried beneath and stifled by its representations.

I was especially interested in how Aerochrome perceives and makes visible an imperceptible part of the light spectrum. In almost all of my work I struggle with the challenge of representing abstract or contingent phenomena that are virtually impossible to see, or at least very difficult to put before a camera lens. This is especially the case in Eastern Congo, where my subject was inherently hidden. From the little I had learned about this conflict, as well as from my past experience working in similar situations, I knew ahead of time that my subject would elude me. Rather like Marlow on the steamer, I was pursuing something essentially ineffable, something so trenchantly real that it verges on the abstract.

The rebel fighters that I hoped to photograph are hunted by the Congolese Army and by rival rebel groups and the local Mai Mai. They emerge from the jungle to loot and slaughter - this is how they survive - disappearing into the foliage just as quickly. Because it’s possible to exhaust the civilian populations that they prey upon, these groups circulate nomadically in the region. They live by bivouac, constantly moving.

Where fighting has occurred, it’s trace can be difficult to perceive. Instead of bricks and mortar, Eastern Congo has provisional shacks and a rapacious vegetation that swallows history. Instead of hellfire missiles and military barracks, there are “white” weapons, machetes that kill silently, and rebel militias concealed not by concrete and camouflage, but by the jungle itself.

The decision to use colour infrared film forms a dialogue with these specifics. The poetic associations carried by the pink and red palette are a by-product of this conceptual framework, but a very fertile one. It’s an allegorical landscape - La Vie En Rose - steeped in a kind of magical realism.

Susan Sontag pointed out that photojournalists have long avoided the ethic/aesthetic dilemma by ‘flying low artistically speaking’, using grainy black and white film to appear sober and objective while portraying human suffering. I feel that it’s equally valid to explore the camera’s full aesthetic potential. Naturalism is no greater claim to veracity than other strategies.

I was searching for a new form, or generic hybrid, that would go a step further. While making the work, I was acutely aware of the fact that infrared light is invisible, so I was literally photographing blind. The whole process seemed preposterous. I felt like the protagonist in Gogol’s Dead Souls, quantifying an absence using a meticulous scientific method while engaged in a picaresque trajectory through an impossible land.

JC: Flying high artistically speaking might generate the same - or similar - problems, though, because it might hide the problems you’re concerned about by making people only talk about the way things are depicted and not what is depicted?!

RM: The subject of my work in Congo is the conflict’s intangibility, the irruption of the real beneath the generic conventions - it is a problem of representation. The word ‘infra’ means below, what is beneath. A dialogue about form and representation is one of the work’s objectives, so I don’t think it’s a bad thing if people get hung up on the way Congo has been depicted, rather than what is being depicted. That’s the point, really.

However, I would take issue with your question. More elaborate art forms are no more opaque than seemingly ‘transparent’ ones. You simply have to look to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness for an example of a highly aestheticized, innovative and very challenging work of art powerfully hammering the specifics of a major human rights disaster. The novel also speaks more universally about the human condition, about the lure of power, and the endless, pernicious, self-destructive trajectory of unstoppable ‘progress’.

Rather than eclipsing or outshining its subject, Conrad searches for the most visceral, impressionistic, fearful and personal voice to describe the horror that he has witnessed first hand. His account has outlasted any of the era’s other representations (documentary or otherwise) of Congo’s tragedy, surviving as a testament that reminds us of the horrific background to the current situation, of the recurrence of history. All of this is borne by a work of fiction.

JC: Of course, there’s also the problem that we live in the Age of Photoshop, and people might just think you simply changed colour using a computer - which, given the growing number of photo-manipulation discussions - might make people focus on the colours and on whether or not what they’re seeing is actually real, instead of the actual subject matter. Were you concerned about this?

RM: Using colour infrared film and making Photoshop manipulations are both creative decisions. There’s nothing more or less truthful about either of them. However, the decision to use analogue infrared film refers to the specificity of that medium, its genesis as a military technology, its potential to reveal the invisible, and a host of other factors. Infra is concerned with that specificity, and a deeper understanding of the work does require the knowledge that these images are the result of a particular kind of film that is sensitive to infrared light. This is why I renamed the work Infra (it was originally titled Quick, after the film’s potential to differentiate between the quick [living] and the dead), to emphasise the decision to use infrared film.

JC: Given your choice of film it seems you might have a problem with how conflicts in Africa or the continent itself are usually covered. What is your take on this complex?

RM: The idea of a ‘story’ to be ‘covered’ reveals a photojournalist’s task. Journalism is extremely important when it comes to representing conflicts. But it is not the only strategy available. There’s a range of art forms beyond photojournalism. Since they’re not as concretely instrumental as journalism, they give us a whole lot more space to breathe. That’s very important because the world is a complex place.

JC: Can you talk a little more about what you mean when you talk about art forms beyond photojournalism? What role can art play? And needn’t we worry about art being seen as, well, art, in other words something that’s “just made up”?

RM: I feel strongly that something that is ‘just made up’ can speak more powerfully and more clearly than a work of journalism.

At the end of the day, I feel that journalism’s premise is often not simply to inform, but also to affirm our world view. I take issue not with its informing role, but with this affirmation. I believe that it’s imperative to challenge our thinking, particularly in more volatile and loaded landscapes whose narratives are frequently calcified by mass media interests. My work is not intended as a criticism of journalism (which is tremendously important). Rather, it operates within the open field of contemporary art, where the emphasis is not on the answers, but on the questions - not on the facts, but on what they add up to.

[Thanks to Patrick Henry from Liverpool’s Open Eye Gallery for giving me Mark Sealy’s fascinating text on Alice Seeley Harris published by ABP Autograph.]

Images courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery. Produced with a Leonore Annenberg Fellowship in the Performing and Visual Arts.

By

By