A Conversation with Rachael Dunville

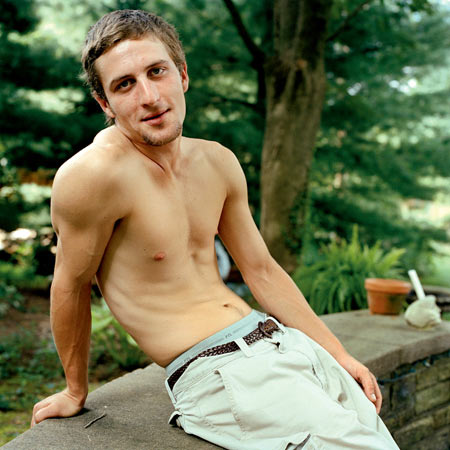

It is no secret that I am particularly interested in portraiture, and a photographer who lately caught my attention is Rachael Dunville. I asked her whether she would be available for a conversation, and I was happy to learn that she was.

Jörg Colberg: You take portraits. What is it about portraits that makes you take them?

Rachael Dunville: It is primarily the process of making the portrait that drives me. When else in life do you get to invite any person you wish to willingly engage with you in a space of entirely rapt and reciprocal attention? Both of you are staring at one another, nervous, self-conscious, and yet basking in the act of being present with someone else. I love witnessing each fantastic detail: the wisp of light on every plane of flesh, the language of the body and voice, and just…wow! Too many elements to list. There are not many things on a daily level that are this special.

I think it started with an awareness of the satisfaction that came in looking at a photograph and feeling deeply connected to it as an object. There is one event I vividly recall, where the person in the photograph felt alive to me through the object. I was 16 years old and it was well before I would have called myself a photographer. I had a crush on a boy whose appearance made me swoon. So one day I made a casual photograph of him looking at the camera, and rushed to the 1-hour photo lab to have the roll processed so that, in a way, I could see him again over the weekend. The photo looked and made me feel differently than he did in person, and noticing this was revolutionary. To this day, I recall staring at his photo for hours, day after day, and my heart feeling like it would burst with pleasure - not because of anything about him in person, but rather, that the look he was giving me through the camera (evidenced in the photograph) was so penetrating. He was looking into me. I was aware that it was the photograph with which I had this relationship and not exactly the boy. Something in the photograph as an object was more gratifying than was he or the thrill of my crush. It felt more direct than when we were in person together.

Nowadays, I have tapped into this same experience with a similar exercise, but on a deeper and more complex level. In addition to the connection to the object and the lasting impression that happens in staring into a portrait, I now swim in a sea of complicated pleasures that exist in the act of making a photograph. I still feel an aesthetic kind of “crush” on people, and let that drive me to engage with them in a session of making photos together.

JC: This begs the question then at how the third-party viewer enters the picture? Do you ever take portraits with the viewer in mind, maybe thinking about what other people might see? Or is that something you never think about?

RD: The viewer is very far from my mind when I am making a photograph with someone. In fact, the act of photographing - of composing the shot and handling the camera, etc - is only part of what I am thinking about at that moment. I tend to work intuitively, and find myself trying to stay open, trying to establish, maintain and challenge the connection between my subject and myself. My audience only comes into consideration when I am editing or sequencing work (at a much later date). To be honest, next to shooting, editing is the most pleasurable work. It is less intuitive and is a much more cerebral affair. I prefer to edit after much time has passed, which allows me to re-experience the encounter, and then, directions for a series often present themselves at this exciting stage.

JC: I’m not sure whether you would agree, but it seems to me that in portraiture the weight of what one might call “tradition”, all the photographers who took portraits in the past and whose work is well known, might be heaviest. How do you see yourself in this photographic tradition? Did you study what people did before, to arrive at your own style?

RD: I grew up in a small town and was obsessed with looking at art books. They were my primary link to the world of art. Studying images by painters and photographers was a huge part of my education, and surely had an impact on the development of my “style.” I also come from a strong background and love for figure drawing and painting; Eric Fischl, Alice Neel, Lucian Freud, and Egon Schiele were some of my heroes and remain inspirational to me. In my own sketches, though, I found that it wasn’t the traditional, classical nude or head-and-shoulder portrait that interested me as much as the body and its expressive ability to communicate something deeper about humanity. I had trouble expressing this in my painting and drawing during college, or at least it took me so much time to embody a person in paint or charcoal that I was constantly dissatisfied. It wasn’t long after that I took my first photography class, learned about F-stops and shutter speeds and started making photographic figure studies instead. I started exploring what I wanted to communicate through the process and conditions that were involved in making portraits with a camera. I immediately loved the directness of the medium, and quickly developed a similar directness in my approach to subjects.

I think the part of “traditional” portraiture that I relate to most is the seriousness of the act. The stillness. I literally hold my breath, and often, so do my subjects. We are frozen in a very live moment, before the shutter is even released. Traditional portraits, to me, present a potent distillation of character in a single frame, and this is also something I attempt. The technical simplicity of photography (or at least of the way I choose to work) allows me to keep the focus on the connection between the subject and myself.

I see influences in my work (which I pleasantly discover popping up on my contact sheets) from all kinds of various non-photographic sources, but my two heroes in photography - the ones who influence me the most - are both quite traditional, I suppose. I discovered them on the same day, a year and a half into the making of my Springtown body of work. They are Peter Hujar and Mike Disfarmer. I deeply relate to them, each in specific ways, and sometimes like to think that some kind of channeling happens between my camera and these two portrait-making geniuses. And in talking about sources of inspiration, I must mention Joni Mitchell. She has been my favorite artist since I was a child. Studying her journey has been, and continues to be, my most consistent source from which I draw inspiration. Because of her, I honor my own vision and keep opening myself up to try and better communicate through my artworks and writings.

JC: I have often wondered why so many photographers have a… let’s call it complicated relationship to painting. Seeing your photography and the artistic skill at display it is somewhat hard to understand how you would be unable to express in painting what you manage to express in photography. Do you have an idea what it is that allows you to take photos that you would not be able to paint?

RD: I do have an idea. For me, what I express comes not in the skill on display, but in the skillful interaction that is then translated to the photograph.

I was never very interested in technical mumbo-jumbo. The practice and dedication to technique involved in drawing and painting were simply not immediate enough for me. That pace couldn’t keep up with all of my ideas. With that said, I turned to photography based solely on the fact that it satisfied a fierce drive in me to be extremely prolific, to be extremely experimental, and to delve into complicated subject matter. Now, I will admit that when I go to the Met on any given Saturday, I ache deeply when I view the etchings and paintings, knowing that I still wish I could master that expression. However, I feel the same ache when I see gifted dancers of any kind, or read ecstatically written prose. I’m still learning that, though I’m young, I may not be able to do all things with the intensity that I do my photography. And that’s okay because I believe all of that inspiration and desire feeds into my photos.

JC: How do you approach taking a portrait? You wrote that “I approach the transaction of making a photograph of and with another person as an intuitive, magical exchange; a subtle seduction between willing participants.” How do you get your subjects to open up to you and the camera?

RD: Part of how I “get” them to open up to the camera and me is by not “getting” them to do much of anything. The most direction I give is to ask them to sit close to the light of a window, or out of the direct sun, for example. I approach photographing as a very serious act, and yet I balance the seriousness I feel inside with a casual, non-technical and carefree presence. Anything goes, and it creates a safe arena - for us both - to just be.

I often think that the best training I received in college for being a portrait photographer was in being a waitress. I had mere seconds, under pressure, to connect with any given type of folk that were traveling through the Ozarks on old Route 66. This forced me to engage with a lot of strangers, and also taught me to truly sharpen my antenna for reading people—to find out what we had in common, and what they needed most out of our short time together. Yes, it was just part of being a waitress, but it was also great practice - what I do now when photographing strangers is much the same. Even in photographing someone I’ve known for years, I still have to intuitively navigate and nurture what brings us together in that moment of making an image.

I have a theory that attention is a missing element from most of our lives. People need to be noticed and given the gift of real attention, the kind that honors the most mundane details that makes up a person. Has anyone ever recited to you the exact placement of the scars that interrupt your freckled countenance? Have they noticed the peculiar way you stand when you stir your stovetop gravy? Or your shift of mood at a particular time of day? Making these observations, and acknowledging them, is flattery in a very potent form! I relish these small elements and energies in people, and feel proud honoring them as they are, in both my writing and my imagery.

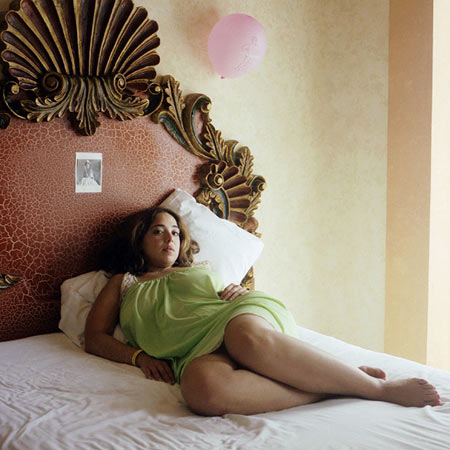

My most important job in the process of photographing (besides loading the film correctly), is to be a good listener. I am truly interested in people and love to hear every detail about whatever someone may wish to discuss. People often share, not only their appearance, but also highly treasured personal musings. The air between the camera and sitter becomes a very sacred space of eye contact and open hearts - though I’m not sure anyone’s aware of it besides me, and maybe that’s a good thing. Keeping it light is also important. But that’s part of that unconscious oscillation. I’ve had both family and strangers alike share some of their deepest and most protected thoughts, secrets, and feelings during our time together. I treasure this aspect of my sessions, and, like a mother robin, protect the nest in which I watch over these highly sensitive eggs of spoken words. The resulting image often unveils a trace of this hidden treasure.

Listening, of course, includes much more than just hearing stories. People want to be heard, cared for, understood, admired, and paid attention to - there are sensitive chords of need and want in all of us. I think that in being photographed, a tight web is spun around all of these desires until it forms into a compact little package of penetrating emotion, and that is what is often expressed and read in the portrait. As the photographer looking in and around the lens, it’s a complicated and thrilling thing to watch emerge, evolve and disperse - and then to view and contemplate it again, in the imprint of the remaining photographic object.

JC: And when you see someone whose portrait you would like to take do you have images in mind, or do you let things flow, to see what you will get out in the end?

RD: No matter where I am, I see at least one person per day that I crave the opportunity to make a photograph with. And it is a true craving, full of aching and eager energy - my imagination is rich and overflowing with images I wish I were making. It’s like I’m already photographing, I’m already composing images (but without the camera in hand).

I find myself studying people, taking mental notes of what I’m a witness to, what I see, feel and hear. When I see someone I want to photograph, it is like a little heartbreak creeps into my chest, and I am instantly regretful if I do not go and connect with that person in some way, even just to extend a compliment. I like to feel out the energy of the person, which isn’t something I can put into words easily. I look for familiarity, coquettishness, and a sense of a mystery I wish to solve. I may study you for years and never photograph you, or I may meet you one afternoon and photograph you the very same. But no matter what the circumstances, I go through this process with each and every person, and it’s something that happens to me daily.

When I am actually inside the act of making photographs, I absolutely let things flow. Before I even begin, I try to release any expectations or anticipations of what I may think will transpire, and in the end, am always astonished by what just took place. A typical shoot progresses through a dozen or more emotions and reactions to the camera and to each other. All along this trajectory, I make images - though the work I show is not from any one stage of this process. I find all of these moments to be extremely interesting and important to pay attention to, and to record.

In many ways, making a portrait can be akin to making love. Within the spontaneity of the encounter, you cannot talk about the way it will or should happen. You cannot plan the way it will unfold, or it will be static, rigid and unsatisfactory. You have to trust that you will know what to do when you release control and submit to the whim of the moment. When I shoot, I just feel it out, without thinking too much, simply enjoying their company and the opportunity to look, with glorious impunity. Each moment isn’t about “the shot,” in fact, not a single photo is made with this intention. It comes from looking deeply into one another and finding pleasure in that intense attention that is really just an intense circuit of energy fusing between us - no matter what the dress code.

JC: There is the chance encounter, and there is the presence of someone you know very well - which in love making leads to different results, with the thrill of the former case replaced by the deep trust and intimacy shared in the latter case. Do you ever go back to subjects whose portraits you took in the past to take another one? Even if it was just to see what you’d get? Or is the thrill gone after the portrait has been taken (and you have looked at it many times while printing it)?

RD: Yes, of course. I constantly go back to people to make more portraits. In fact, there are about a dozen people that I have a long-term photographic relationship with, in addition to a deep friendship that has developed because of or has evolved through our consistent photographic encounters. And that “thrill” you mention is ever present inside of me when I have the opportunity to photograph. It may come as no surprise that the chance encounters are challenging in their own way, just for the mere fact that we’re pushing ourselves into this dynamic experience for the first time.

In contrast, once a long-term relationship with a person has developed, it becomes a much more distilled process - each and every time is a new challenge to go beyond where we’ve been before. We may be less awkward or more intimate but the intensely interesting images come as a result of exploring deeper every time and getting something truly meaningful to emerge. The truth is, after ten years of studying a person and their contact sheets, I know what looks good in the end, but that isn’t very interesting is it? I don’t think so, at least. I always make myself push the situation so that I’m not just making a good composition, but am making challenging images; ones that may cumulatively say something important over time.

My relationship to certain images also keeps evolving. I keep getting to know my photos, as objects, as icons, as guides to my process. Because I feel love for the people I shoot (even strangers) I don’t get sick of looking at them. To this day, every time I pull up a file, or start making test prints, I will say embarrassingly loud, “Hi Andy!” And then I’ll usually call the person and tell them that I’m thinking of them, or have been looking at them all day!

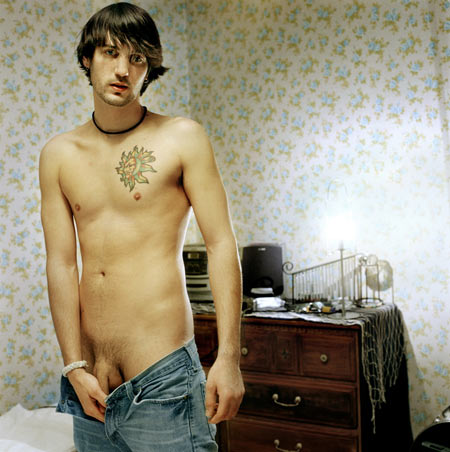

JC: Part of your work shows your subjects naked or partly naked. When you take such portraits, is there a huge difference in how you (and your subjects) approach them? Also, given that nudity still is such a loaded topic - at least in the US - what part does the nudity play in the portrait?

RD: I want to be clear that every single portrait session starts off the same. I don’t decide ahead of time, “today I want to make portraits of so-and-so in the nude.” Like I said before, I search for a flow, for rapport to develop between my subject and myself and I don’t make suggestions about clothing or otherwise. And as you’ve noted, some of my subjects end up naked or partly naked. But that is the result of an evolution that happened in the moment, when the camera was present and we were attentive to what was emerging between us.

Clearly nudity does not bother me. I started drawing friends and family in the nude at a young age and modesty was never an issue. In my work, the body is an important element. I think people feel comfortable sharing both their bodies and their thoughts with me because a connection of trust has been established, and furthermore, I am comfortable sharing right back.

And if there is nudity in a portrait, I’m definitely aware of how commanding a role it plays. First of all it gets people’s attention, whether complimentary or critical. It complicates. It challenges. And, to me, it is just so satisfying to view in art, in real life, in our imaginations! Who can resist a glimpse of the beauty, complexity, mystery, and attraction of delicious fleshy flesh? I am, without a doubt, drawn to the sensual, the erotic, and the provocative. But regardless, I strive to make images that will satisfy a viewer on whatever level they happen to enter my photograph. If it’s to revel in the surface details of bodies, you’ll be quenched. But if you choose to seek deeper, you will be supported in your emotional curiosity and escorted into something potentially quite challenging and, hopefully, rewarding.

The gaze of the artist at his female muse has been ingrained in us, socially, from very early on. My subjects likely feel the same intense affection and attraction acutely pointed in their direction as all other models throughout art history have, and I realize that as a young woman doing the gazing, I am upending the relationship as it has traditionally stood. Everyone responds to that energy differently. Like I mentioned, at the outset, I do not approach someone who may end up partially unclothed any differently than someone who is standing there in their ski clothes. When someone takes his or her clothes off (partially or fully) it is almost never a predetermined factor, but is more an evolution of desire. That desire is not necessarily sexual either—some people are genuine exhibitionists, or want to display themselves in a way they think I, or others, want to view them. Sometimes people just want to express something a little risqué and our session may provide an outlet for that. All of this is very interesting to me and, again, I allow that to unfold naturally.

Other times, I think nudity is actually a veil obscuring a potentially deep emotion from being experienced. For example, when you see a portrait of someone who is nude, the reaction is often, “Oh, that’s so intimate.” People perceive that just because they are seeing someone differently than how they would if they were to meet on the street. But it can be a false “intimacy.” I am seeking something deeper and more penetrating than just a loss of clothing. I think some of the most “intimate” images, or “nude” - both, here, meaning vulnerable and stripped - are not always the ones you’d expect.

By

By