A Conversation with Peter Granser

When I received a review copy of Peter Granser’s Signs in the mail, I had quite a few questions about the work. And since I had always admired his earlier work about Alzheimer patients, I asked Peter whether he would be up for a conversation.

Jörg Colberg: After Sun City and Coney Island

now it’s Signs

, photography done in Texas, with an emphasis on political and religious fundamentalism. On the one hand, the results, which mirror the place, are spectacular, on the other side the question remains if such an image of America isn’t a bit too simple and one-sided? Is it possible for a German, who does not live in the US, to portray the country?

Peter Granser: America was never good in criticizing itself, and it was also never really interested in opinions from abroad. Especially because of that it is important for outsiders to critically examine this country, which via almost every development and decision in politics, business and culture influences other countries.

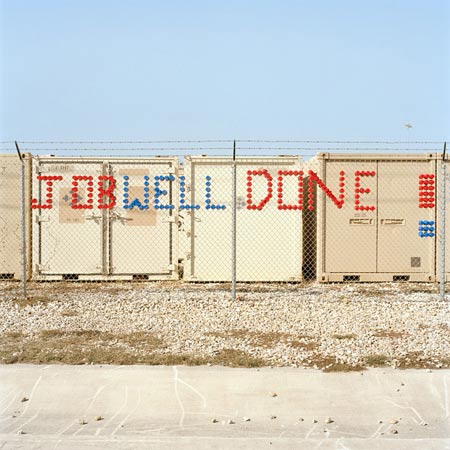

The America I show in Signs is the conservative America, which over the past years has caused a lot of problems for the world and itself, problems which also won’t disappear with a change in president next year.

Of course, Signs is hyperbole, and I intentionally picked Texas to focus on this exaggeration. I know that not the whole country stands behind these “signs”, but one has to deal with the questions that Signs

talks about. The locations I photographed I don’t find spectacular, though. For me, stagnation and emptiness prevail. The sole exception is the megachurch, which because of its size (it seats 16,000 people) and its production of course is impressive.

There recently was a review of Signs in Süddeutsche Zeitung. I can’t think of a better way to express what Andrian Kreye (formerly a US correspondent for many years and now head of the “Feuilleton” [German version of “arts & culture” in newspapers]) wrote:

“Since the foundation of the US it was often Europeans who cut to the chase of America’s sentiments. The classics range from Alexis de Tocqueville’s studies of ‘Democracy in America’, to Robert Frank’s photo book ‘The Americans’, to Wim Wenders’ ‘paris texas’. In a country, which so consistently works on a homogeneous cultural identity, the view point of outsiders is so focused because they discover so much in the every-day life that is very basic. The German photographer Peter Granser also has been traveling across the US for years. In his two stunning photo books Sun City and Coney Island

, with his melancholic view point he reduced the colourful side of the US to sun bleached ruins of the American dream. With his new book Signs

he now presents an essay about the conservative America, which in its minimalistic directness deeply penetrates the mood of the country that is at a historic turn-around point. The photos were taken in Texas, that is in the very state, which George W. declares to be his home and in which strict piety and defiant combativeness combine to a unique attitude that is so alien to us Europeans. Granser avoids becoming polemic. His photos are guided by the sometimes subtle, sometimes confrontational signs left by this society in the empty Texan landscape; they are guided by the clear view of the outsider who knows a lot, but claims nothing.”

In 2005 you wrote: “Maybe you need to be a foreign photographer to find the essence of a country. Peter Granser’s Sun City certainly finds the quirkiness of American life - something local photographers never quite get to…….. “

I can only agree.

JC: This comparison is a bit flawed, though, because even though the foreigner might find it easier to see the “quirkiness”, it’s questionable whether s/he will be able to see the more profound problems as easily. And an American critic probably would turn Andrian Kreye’s last sentence around (thus mirroring a popular stereotype of Germans): “guided by the clear view of the outsider who doesn’t know anything, but claims a lot.” Signs, I think, strongly polarizes, and that way there might be more rejection in the US and acceptance in Germany (partly based on anti-American sentiments, which are, after all, fairly widespread) than the subject matter can handle. After eight years of polarizing, to a large extent caused by George W. Bush, wouldn’t it be time to talk to each other softly instead of using hyperbole?

PG: Some critic might turn the sentence around - go for it! The work is not done to be liked by everybody. Signs is not supposed to be a sign for something as it really is, but in the sense of a metaphor. I received enough positive feedback from American curators and critics to know that my work is correct.

Signs is intended to polarize and to cause debates. The work is no didactic picture book, which offers manifest answers for open questions. Instead, it is intended to produce questions and to thus facilitate a dialogue. Especially ahead of elections I find this very important.

JC: I would be interested to learn to what extent you had already planned in advance what to show. In an interview on “The Sonic Blog” there is frequent talk of a symbolism, for example, “This image symbolically stands for the whole misery of the Iraq war and the Bush government.” To what extent did you look for images in Texas or, to ask this in a different way, did you have some sort of “master plan” that you then only had to fill with images?

PG: Of course, I did research before my trips. But during my first and third trip I only had a vague idea what areas of Texas I wanted to see. All in all, it was spontaneous decisions that guided me through the country. Only the second trip was more organized, since I needed permissions for the army, the mega church, and for NASA. Most images I found by chance. After all, how would one a priori find a place with a sign “Never Hillary” or “Job Well Done”?

In addition, there were tips while being on location. Anne Tucker helped me a lot, as did strangers on the road with whom I got talking. One of those was Barry Vacker, a native Texan, who teaches media and cultural and utopian theory at Temple University. I met him somewhere at the Rio Grande. We started talking, chatted about Texas and the US, and in the end, he wrote the very exciting essay for Signs.

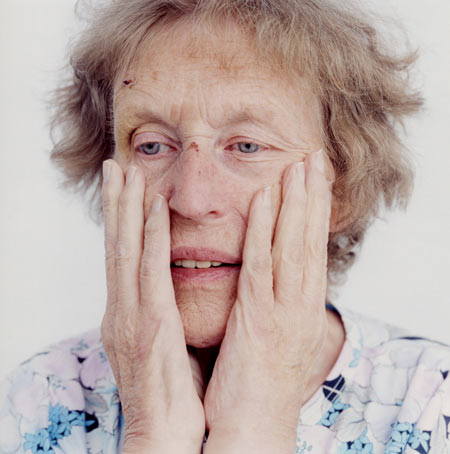

JC: I think my favourite project of yours is Alzheimer, a photographic investigation of the illness of the same name. I’d be interested to learn how you found the idea for it and especially how the project developed. Was dealing with Alzheimer patients harder than with healthy people? Were you in contact with the families?

PG: With Sun City and Alzheimer

I found two ways to deal with our aging societies. “Sun City” was done first. There, for the first time I learned about Alzheimer research. In 2001, I was chosen for the World Press Masterclass with a portfolio of Sun City

. The twelve chosen photographers are assigned the same topic that they have to work on over the Summer. In 2001, it was “identity”. After thinking about it for a long time and after some research I decided to do Alzheimer

as work about the loss of identity. After the Masterclass I continued to work on the project, and thus the book was published in 2005.

I did not find it difficult to deal with the patients. Before that, I had had to deal with psychiatric patients, and I was not afraid of dealing with them. I only needed a few days to get used to the disease and to its symptoms. Of course, it’s easier to deal with healthy people, because you can communicate with them. At the Gradmann-Haus near Stuttgart, where I took the photos, this was impossible, because the patients were all in advanced stages of the disease. They were unable to speak intelligently, didn’t remember anything, and didn’t perceive me as a photographer. That made work difficult and time consuming.

For many Alzheimer patients, touch is the sole way of contact left. So it happened almost on a daily basis that one of the patients came, took me by the hand and wanted to go for a walk. I spent many days walking with the patients in the garden or in the inside of the home instead of taking photos. For the portraits I needed the help of relatives or of the nurses. Some of the patients were very restless, and they were moving around constantly. In contrast, others were apathetic. In an opportune moment we had to try to convince the patients to sit in front of a window (I only worked with natural light). Some got up immediately, and I only had time for one photo, others stayed for an hour or two.

In order to be allowed to take photos at all, I needed the permission of the administration of the nursing home and of all 24 families of the patients. That took a while, and I had to convince the relatives that I was not after voyeuristic work, but after sensitive views of the faces and gestures of the patients that otherwise nobody looked at. After a while I was able to convince them that it was important to bring this topic to the public eye (In 2001, there was not as much public awareness of the disease). Alzheimer’s Disease is a social challenge for our societies, and I wanted to trigger discussions. Fortunately, the relatives understood this.

JC: And what reactions did you run into after having finished the project?

PG: The relatives were very satisfied and happy with my portrayal of the disease.

For me, the most important reaction I received from a lady who told me that she had never been able to understand her husband’s illness (who had long been unable to recognize her). For years, she had held on to the old image of her husband. However, my portrait of her husband helped her to see that her husband had become a different person, and she was able to accept the changes caused by the illness.

Of course, there are always people who do not understand the work. Occasionally, I was being accused of being voyeuristic and of exposing the patients to ridicule. But I know that I left them their dignity even though they were unable to control the process of portraiture and even though they did not understand what happened. The majority of the reviews were excellent. In 2004, I was awarded the Arles Discovery Reward for this work and Sun City and Coney Island

, and the book was sold out rapidly. The second edition will be released by Kehrer publisher at the end of 2008.

JC: As someone self-taught your photographic background differs from those of many other artists. How did your photography develop to where it is now? Were there influences or role models that you used to orient yourself?

PG: Of course, there were influences. I was amazed and influenced especially by American photography or photography done in America such as by Robert Frank and Diane Arbus, extending to William Eggleston and Stephen Shore. In addition, there was Martin Parr, whom I met during a common exhibition. He caused me to start taking colour photos in 1988 again. Of course, there is a strong contrast between my colours and his.

JC: As a member of Piece of Cake (POC) you are connected to a European network of photographers. I often think that such groups offer enormous advantage, and I often wonder why they are not more common, especially in the internet age. How did your POC membership come about, and what advantages do you see in this type of group?

PG: Since Charles Fréger recently talked about POC I can here focus on my own personal reasons.

A network like POC does indeed offer many advantages, but it also means quite some work for each individual. What’s more, you have to be able to open up to others and to work in a group. Maybe those are the reasons why there are not more groups like that. And we do not have commercial interests like an agency.

In 2004, I read an article about POC, and I liked the idea very much. As a consequence, I applied and I became a member right away. I first met POC at a workshop in Cologne. There are very nice people in the group, and the meetings always are very motivating.

POC offers me the possibility to talk intensely with the other members about new work and about photography in general. For me, that is very important to challenge my own opinions. As someone self-taught I was missing this exchange, and I am very glad to have found a group like POC, which gives me the feeling that I’m not alone.

By

By