A conversation with Misty Keasler

I had been aware of several of Misty Keasler’s projects, but it took me a while to connect them with the same name. Misty has covered topics ranging from people living in huge garbage dumps to Japanese love hotels, and I was curious how she managed to do this so (seemingly) effortlessly - so I asked her.

Jörg Colberg: I think one of the hardest problems for many photographers, especially aspiring ones, might be to find good projects to work on. Your portfolio contains an amazing variety of projects, ranging from people living in garbage dumps, to orphanages, to Japanese love hotels. How do you get the ideas for such a wide range of topics?

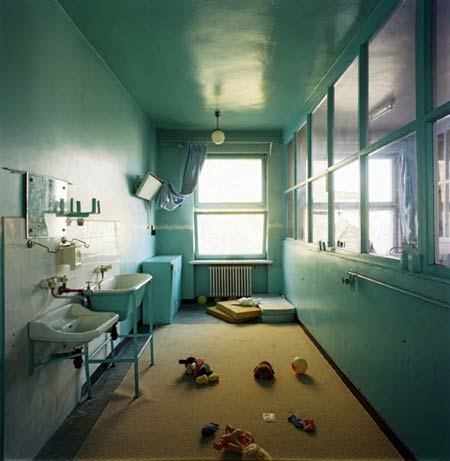

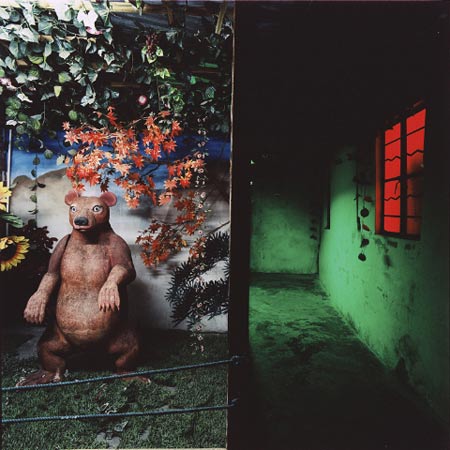

Misty Keasler: Early on I had a professor who said there are many great photographers in the world who have nothing interesting to shoot. When I was a student I was so easily shaped by my professors and every thing I read or heard about photography and so that comment made an impact and made me realize once I had the tools and the skills to manipulate film any way I wanted, I needed to find a voice and reasons for shooting. I am quite curious and love culture, love getting to see and experience things that challenge my middle-class western background. For the orphanage photographs I approached an NGO in Dallas that delivers aide to orphans in 40 countries to see if we could work together and that has lead me to dozens of orphanages. I lived in Japan for a little while and read about Love Hotels in a guide book and thought they would be an interesting lens and study in which to view Japan.

JC: In a recent edition of Harper’s Magazine I read an article about a huge garbage dump in the Philippines, where you went along to take photos. In another series, you covered Russian orphanages. Both these works must have meant quite an emotional burden for you, since I cannot imagine how one would not be affected by orphans or by people who are so poor and desperate that they have to live in an environment of toxic trash to try to make a living. How do you deal with those situations emotionally, how do you process what you see? I could imagine that if you got too involved in the situations, your photography would suffer. Have you ever had problems like that?

MK: I never try to be objective when taking photographs - which is ironic because I believe the finished edited series are much more objective and straight forward than I am (it is important to me that I don’t shove my viewpoint down anyone’s throat, give the audience room to breath and think on their own). But I generally always find that I am seduced by my subjects and I fall in love with them. I think this is quite evident in the orphanage and dump photographs - those series are quite warm and have a warm palette. These are contrasted by the Love Hotels where the perspective is much colder and reflective of the lack of love hastily covered by bright colors and trappings to fill the gap. But to answer your question, I let myself get involved - I sponsor a kid in the Guatemala City Dump and would like to one day adopt from one of the orphanages I have photographed. Sometimes what I have been exposed to keeps me up at night, but I think something is wrong with photographers who can be there, make exposures and leave without being haunted. We need to be challenged and to have our lifestyles challenged. I find a balance between this and dignifying my subjects by making all the series cultural studies, explorations and portraits of spaces and rooms.

JC: To what extent then is contemporary photography an exploration of our culture? And given you’re saying you never try to be objective, it seems like this adds a dimension to what it means to be a photographer that many people would never think of - since photography is supposed to be objective.

A: Well, I think it comes in waves. Art is reflective or reactionary to culture, even if it is not directly documenting or referencing it. Even the work of photographers who work only in the “art” side of things like Cindy Sherman’s self portraits about women’s roles and ways in which we are portrayed in literature or Laura Letinsky who photographed couples having sex and empty tabletops address a specific aspect of culture. Artist who believe they create in a vacuum, who fabricate art for art’s sake are naive at best and ignorantly vain at worst. We are products of our culture. When we create, our culture, our generation, and the ways in which we identify ourselves all come into play.

Since when is photography objective? The camera’s presence changes everything. And film grain, lighting, color choices, even formal or loose framing and format choices change the objectivity of a photograph. I believe my openness to the subjects and subject matter makes me a better artist since I do not come in with a specific perspective I am trying to photograph what comes along the way. And I take enough time to let this happen (which is a sharp contrast to the traditional rules of photojournalism). I do want to draw a line here between my work practices and my photographs. I personally, as the one making the photographs, do not attempt to be cold or distanced with my subjects and quite enjoy their company most of the time. However, it is of utmost importance to me that the finished edit does not shove my perspective down the throat of the viewer and comes at them from a subtle manner. That’s what I mean when I say the photographs are more objective than I am.

Q: But isn’t it then somehow important to make a possible viewer aware of the fact that photography really isn’t objective? I mean, most photographers are aware of this problem, but it seems like the general public still thinks that photography is completely objective - this is for example reflected in the fact that people think that only with the advent of digital technologies photography could get manipulated. Is this something you as a photographer would like to have addressed somehow, or is it good enough to let the public figure it out for themselves?

A: Why would you assume the viewer believes photography is objective? I believe in our modern times with all our technology and debates over who is really unbiased in reporting the facts of the day, and especially in terms of an audience even slightly familiar with art, people do not automatically believe a photograph is objective. In fact, the more formal and polished an image is, the less likely we (as a general audience) are to trust it from the onset as something completely objective, even if it is hard to articulate why. That is the charm to Nan Goldin’s work. She had a formal art background and yet used a snapshot ascetic - loose quick images that look as though they could have been made by any number of people there. We instinctively trust these images more than, say, one of Roger Ballen’s formally composed portraits because they are closer to the snapshots we grew up with from family events and they are within our realm of familiarity (even when the subject matter isn’t). These are instinctive and almost primal reactions but quite ingrained into the western culture we live in, and I would venture to say they are pretty universal for an audience surrounded by photographic capture of all sorts.

JC: I would be curious to learn a little bit about your experiences shooting the interiors of Japanese love hotels. How easy was it to get permission to do that? What kind of reactions did you - as a Westerner - run into?

MK: The first hotel I took pictures of was the Chapel Little Christmas complete with an automated life-size Santa playing piano in the lobby. No one was around (I subsequently learned this is by design in the hotels) so i just got on the elevator, went up a couple of stories and started taking long time exposures in the halls, thinking I had been undetected and stealth. I thought no one had seen me, but I know now they were probably monitoring my every move via video camera. Eventually my terrible Japanese proved itself to be good only for access to hallways and I had a hard time with translators in the beginning. Cultural roles dictate Japanese women should not approach men for sex so the first couple of non-professional translators I approached (I could not afford the professionals) thought the entire thing including tripod and cameras was an elaborate plot hatched to get them alone in a love hotel room for sex. It was a bizarre situation to be in… I tried to stay in a room by myself but was told I it is simply was not acceptable. I heard they don’t like individuals in rooms alone since the anonymous nature of the hotels may facilitate suicide more than other spaces.

JC: Your projects are done at the boundary of classic photojournalism and fine-art photography. Often, it is not even all that clear any longer whether that boundary still exists. While in principle, there is no problem with that, in practice I could see some problems, with fine-art photography, for example, still presumed to create something that is “just” art and thus fabricated. Is this something you are concerned about? And if yes, how do you deal with it?

MK: The art that makes it to the history books, the work that stays with us and has great impact is always tied to the culture of the day and to the current events. Sometimes people don’t know what to do with my work - most photojournalists I know don’t have time for it and I am sure that there are a few people from the art side who would see this as journalism, though I must say that this work has been well embraced by the art world, both galleries and museums and I have been lucky to have some very strong relationships with a handful of curators and many collectors who have been extremely supportive. I think this work is very appropriate on gallery and museum walls - all of the series are cultural studies, examinations of romance or struggle through internal and external spaces. The art that moves me has purpose and that is what I strive for in my own work.

I have always had a foot in both the art and assignment sides of photography and consider it privilege to make all of my income from making photographs shown both on gallery walls and in print.

JC: There has been the occasional debate online about whether to do editorial work or to what extent to do editorial work. It looks like this has never been an issue for yourself. Given that this blog mostly deals with the fine-art aspect of photography (however ill-defined that actually might be) monetary aspects aside what do you think can doing editorial work add to one’s development as a photographer?

MK: For starters, taking editorial jobs, especially the ones I would not be shooting on my own, have made me a better photographer. When I am working on my own work, hanging out at a garbage dump or some other fascinating place, I look for an individual who captivates me and ask if I can photograph them. Or I walk around a neighborhood and find an incredible room with beautiful light and shoot that. But assignments are generally quite specific - i.e. I must photograph this man in this one setting AND still make a beautiful photograph. There is real skill and challenge in that kind of work and it has made me better at taking photographs - tighter in my execution and my broadened my skills with people. And I do not have long boughs of time when I am not creating. The assignments mandate that I constantly, consistently shoot, even if I am not engrossed in a new project of my own making.

In addition, I have been fortunate enough to have some of my personal projects funded at the very beginning by magazines interested in publishing them - much like getting a grant no one else knows about. And since the garbage work has been circulated, I have gotten assignments (like the Harpers one you mentioned) that add to that body of work. I wouldn’t have it any other way. Being in both the art world and the assignment world is the best of both.

JC: And if you had to pick just one single photo - one of your own or someone else’s - to take to a deserted island (along with your ten favourite books and CDs that one always gets asked about) which one would it be and why?

MK: I don’t think you are going to like my answer. I think I would get tired of any photograph given enough time and if it were the only thing I could look at besides the desert island. But if I had to choose, I would probably take one of mine from the roof of my favorite hotel in Antigua, Guatemala. It is a night exposure for about 20 mins and the sky is dramatic and the rooftop breath taking. I just get lost in it, but mostly because I love that hotel and the way I feel when i stay there - all the things one should divorce one’s self from when editing pictures. But it would be me and my desert island and I can break the rules if I want when on said island.

By

By