A Conversation with Miguel Rio Branco

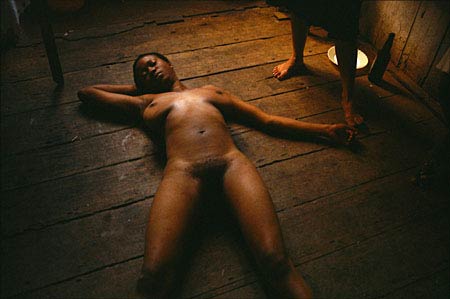

Miguel Rio Branco was a freelance photographer and director of photography for movies when he embarked on documentary photography and was soon noticed for the dramatic quality of his color work. In 1980, he became an associate with Magnum Photos.” I talked to Miguel about his work for Magnum’s blog. (note that some of the images are not safe for work)

Jörg Colberg: When people hear “Magnum” I think many of them will think of classic b/w photojournalism. With its use of often very vibrant colour, your work clearly doesn’t fall into that category. Now colour photography has been widely accepted, but it hasn’t always been this way. Was using colour an obvious choice for you? And since you have a background as a director of photography for movies I’m wondering how much that also contributed to your development of your own photographic style?

Miguel Rio Branco: Today it is possible that when people hear Magnum they are not anymore seeing just traditional Black and white, since there are already some members using color in an expressive way for some time, and also I see that Magnum is growing into a dynamic creative force with many individual paths and not only in the traditional photojournalistic way.

My own work was never only about color since after painting, in the beginning I did most of the time both, black and white and color, as well as experimental films (New York 1970-72). What happened is that in 1980, while living in São Paulo, my archives burned, and what was left were mostly the color slides that were traveling with me.

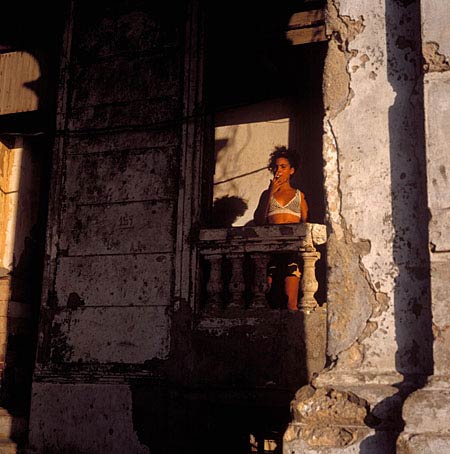

And my color, when I look at it now, I see it has not being really very colorful. Most were monocromatic, with some red and sometimes some blues here and there. Never the whole rainbow. One of the things that shows is that there is a dramatic use of color, and this relates a lot to my painting background. But painting is not only the background since I am still painting again since the mid eighties .

The other link is with cinema and music.

I was never really aware of the big names in photography until 1974, and this after already six years of using photography as my main medium. I lived in New York from 1970 to 1972, and never saw one exhibition of photography; my contacts were mostly with artists and movie people. So my influences came definitely from painting and cinema.

The act of editing came from the audiovisuals that I did at the time, the framing from the movie camera, the not cropping afterwards came from that situation as well as the lack of many verticals .

So my photographic style is basically a non-linear style, which depends very much on the construction of the images, the poetic links created with the images, and not with a linear aspect of framing and use of light and color.

JC: Was focusing a lot of your attention on Latin America an obvious choice for you, and if yes why?

MRB: I always focused on what was around me. I was never really very much into the immediacy of certain subjects. I did Latin America when I was in Brazil, not as a Latin American consciousness (this extraordinary need of identifying races is very American…), New York when I was in New York, Paris when I was in Paris. Not a real traveling photographer. And basically those last 15 years, there is not a real work in Brazil. So: definitely I was never really focusing on Latin American subjects because of a need for identity or something like that. Since I was the son of a diplomat I lived in Portugal, Switzerland, New York; and my grandmother was French. I feel very much as being part of a whole, and this whole is not this or that, it just is. Not a true sense of nationality. On the contrary, I do feel a strong need to see people get into the fact that basically, even with all the different cultures, we do all have the same problems .

JC: Often, the boundary between pure fine-art photography and photojournalism is not that clear. When I look at your work I’m under the impression that you never really worried about what your actual role was but that you instead focused on creating the kinds of images you wanted to see. Is that so? And how do you view this gray zone, where fine art and photojournalism intersect?

MRB: The boundary between fine art and photography is clear at least to me. Between fine art and photojournalism it is the same. What I have seen lately is mostly commercial [photography], or technical or photojournalism, becoming “ART” just because of its size or because of who in power says that this or that is ART .

To me Art is a question of: first, having something to say from the inside that has nothing to do with description of reality, reality being just the material thing that the camera captures. So for this question I must say that I always focus on the images I want to SHOW, not necessarily to see, some of those images I would even want NOT to see. I do create images that, when related to others in specific constructions, make sense, create rhythms and bring emotions to the surface.

I don’t see a gray zone: just some works that are art and others that are not, and this has nothing to do with being photography, objects, sculpture or happenings. People today are just afraid of saying that they do not like something for fear of not being… fashionable .

I guess we can see Art in a traditional picture, from someone without the conscience of the Art market, more than from today’s conscious “artists”, [which are] professionally directed to the Art market.

We are in the word dominated by propaganda, advertising and marketing. And in this kind of world, anything can become art. You just need a good salesman.

JC: So when fine-art photographers go to places like New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, take photos there, and then exhibit the work in museums or galleries - is it art? Even though it documents a real event and, by extension, what happens when the government simply refuses to take care of business? Or is it journalism, even though the photographic language used is clearly taken from the art world and not from photojournalism?

MRB: I think that it is not the fact that your work is being exhibited in the Museum that makes it a work of Art. I don’t think Museums are free from influences by curators linked to galleries, and from the speculation of the powerful art market. Just have a look at the Chinese art that you see in the auctions, and you will see that something is wrong there .

JC: You have been a member of Magnum for quite a while. How did being a member of Magnum benefit your work, and, looking back, how do you view its evolution since when you joined?

MRB: I never became a member really. My status is [that] of a correspondent, you could call this a collaborator maybe. I have some of my work distributed by Magnum, and still enjoy meeting some of the members, mostly whenever I go to Paris. I stayed a nominee for two years, 1982 and 1983, and then I felt the need of not having to prove anything about my needs to create. I was back in Brazil, in Bahia, and getting back to painting. So my way was never doing just photography or just film or just painting. I needed this freedom, and Magnum at the time was very much orthodox in its way of seeing photography. So I can really say that being linked to Magnum never really benefited me very much in a financial basis. And, in the Art people’s way, on the contrary since some Art-related people think art has nothing to do with photojournalism; and I have been told many times that I should have left Magnum because Magnum is JUST photojournalism . The case here is that I do think I am an artist, but I also think that some of my photographs do have a very useful life in press, and I feel that I would be just too arrogant to say that photography does not also have a practical, useful service to make.

Today this also is changing. I just hope that someday the public will be able to tell what is art in photography and what is just speculative moves.

And besides, Magnum has archives that are quite surprising and [that] can be very powerful when directed into a service for history or a description of life, as well as some strong artists/photographers.

My work has had a lot to do with editing, and I think there are many constructions to make with images that exist, made now or many years ago.

JC: I think we are currently witnessing what one might call the transformation of Magnum into something different, even though I will not attempt to define what it might be. But it seems that with Magnum’s inclusion of photographers who very clearly originate in the pure fine-art world and with “citizen journalism” becoming ever more prevalent - anyone with a camera can now shoot a newsworthy photo (see, for example, the photos taken by the passengers of the bombed subway in London), even though this clearly doesn’t mean that everybody is a photojournalist now - things are in flux. What do you see as the role an agency such as Magnum is going to play in the future?

MRB: I never was a real photojournalist, mostly a documentary photographer. For a while I thought a document was interesting. Since the beginning of the 1980’s I was already speaking about the freedom of possibilities that using photography in poetic statements with total control of editing was giving a photographer/artist. The personal work was always more important to me than the document. In 1983, after doing a “document ” of the Kayapo Indians Gorotire, I saw that my way was the personal poetic creative one. Two things happened with this material: National Geographic did an edition of it, which was a total error, a discourse in banality and clichés. My participation at the São Paulo biennale in 1983, with Dialogues with Amaú, an audiovisual installation, was something that opened my mind to the fact that I needed real freedom of creation, something that printed matter, other than a monography, could not give me.

Magnum is possibly the agency, maybe VU is another one, that sees that the originality of each photographer is now more important than the fact that anyone around a disaster with a cell camera can document any disaster. Maybe also the fact that there are many other ways of showing personal, artistic (in the insight sense, introspective even when the pictures are of the “world” outside), original ways of expressing yourself .

We are surrounded by thousands of images, and to make something that goes beyond banality is something that goes further than making a few pictures in a decisive moment. The way of constructing with those images something that makes sense is complementary and indispensable to the completion of a work.

JC: I am under the impression that there is a development towards what you call banality and clichés, and I’m wondering what photographers can do about it. In the end, every photographer is affected in some way or another: Editorial photographers experience being squeezed out of contracts, and I think the emphasis on digital and on photography being democratic (whatever that actually is supposed to mean) I think has given people the idea that photography is something that can be done easily and quickly. How can photographers counter that trend?

MRB: I guess the only way is to have the need of being yourself, with your own identity, and not only look into [what] the market needs. Cultural projects are an open field to show the world, mostly by showing its own creator’s needs of expression. The originality of each artist makes the difference, and not only the way a photographer can do an assignment well. I was always for this difference, and I guess this moment now is very open to this new field of expression.

By

By