A Conversation with Michael Wolf

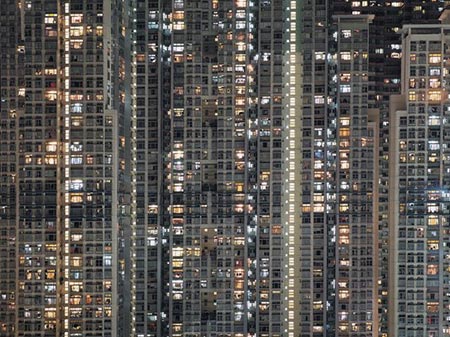

Michael Wolf’s work first caught my attention when I discovered his Real Toy Story project - a depiction of under which conditions the toys found in Western toy stores are assembled. Just a little while later, Michael published Architecture of Density - large-scale photos of some of those humongous apartment buildings in Hong Kong. Given his continued output of interesting work, showing different aspects of life in Hong Kong, I asked him whether he would be available for an interview, and I was delighted to learn that he was.

Jörg Colberg: For your Real Toy Story project, you went to take photos inside Chinese toy factories. Was it hard to get permission for that?

Michael Wolf: Getting permission to photograph in the toy factories was not so difficult - together with my researcher, I contacted more than 200 different companies in the Pearl River Delta in China, and a dozen or so finally agreed to let me take photographs. A much greater ordeal was collecting the 20,000 toys in the United States. As I had set myself a time frame of 30 days to do this, I needed to find 700 toys each day. If I got behind, say I found only 200 on one day, I would have to find 1200 the next day. At one point I was more than 3000 toys behind my requirements, and was feeling quite panicked.

JC: What kind of reactions did you get in the US? Had people made that kind of connection before, that most of the toys - and an awful lot of other stuff, especially the cheapest of the cheap stuff - is being made in China?

MW: When I explained to people at the flea markets why I was collecting the toys, they usually understood the concept and thought it was a great idea. I often prefaced my tale with a story from my childhood: when I was young, my parents had little money and therefore my father made toys for me for Christmas and for my birthday rather than buy something in a store. I remember a big wooden rocking horse and a shooting gallery with animals cut out of wood, which he had built for me. Nevertheless, I yearned for store bought toys because all my friends had them. So being able to go out and buy 20,000 toys really was catching up with something I had missed out on during my childhood. Coming home each evening with scores of bags filled with plastic toys gave me such a satisfying feeling!

JC: In general, in the US the atmosphere has become quite charged after 9/11 and after the quite shameless exploitation of those events by the Bush government, which whipped up paranoia about terrorism for political purposes. Photographers, especially in unusual public places, are often viewed with suspicion, if not outright hostility. For example, while taking photos in a public library - with explicit permission of the management - a security guard asked me whether I was “scouting the place”. Of course, this is nothing new. I once read that the Bechers were suspected to be Russian spies when they started to take photos of industrial places. What is your experience in China? Are people suspicious of you as a photographer? Have you ever had any trouble?

MW: As long as one keeps away from military installations and prisons in China, it is generally not a problem to photograph. On occasion, difficulties do crop up at the most unexpected times. When I was photographing the Bastard Chair series, for instance, on several occasions someone called the police to try to have me arrested for ‘doing something which was harmful to the Chinese state’; my crime in this case was that I was making fun of the Chinese people because I was photographing broken down chairs. I was never actually arrested, but was detained twice for more than 6 hours in a public security bureau and questioned. Both times my films were confiscated.

JC: I am assuming that your Architecture of Density must have been a bit of a change for you, with a different work flow, and (maybe?) quite a bit of post-processing. How did this project come about, what are your experiences doing it, and what did you learn while doing it?

MW: The project Hong Kong: Front Door/Back Door (HKFDBD) of which Architecture of Density is a part of was an idea I was pregnant with for many years. The problem was that I was always so exhausted from working on editorial assignments in China that I could not find the energy to go and shoot when I returned home to my family (I have lived in Hong Kong since 1994.). It was only when my wife received a job offer in Europe in 2002 and the possibility of having to leave Hong Kong hung over my head that I got off my ass and started to shoot - I knew that some day I would deeply regret to have lived in Hong Kong for 10 years and not to have photographed my own personal view of the city. Luckily, she did not take the job, but I got started on my project. At the time I started working on HKFDBD, I was going through a crisis in my photography - I had come to the realization that through working for Stern magazine for so many years, I had internalized the magazine’s style of photography - the images had to be conceived as double pages, be easy to read, and usually visualize a cliche. I felt that my own way of seeing had been corrupted. Every time I looked through the viewfinder, I was framing the photos in the Stern way. I had serious doubts if I would ever be able to free myself from this way of looking. So HKFDBD was an exercise in finding back to my own way of seeing, of freeing myself from the shackles of the Stern magazine style. I switched camera format, instead of 35 mm, I used a 6x7 cm Makina Plaubel, later a 4x5 view camera. Instead of photographing the 7 million people in Hong Kong, I decided to create a portrait of the city with no people in it at all (in the end, the only living beings in the book are two Hakka women, a pink poodle and the shadow of a cat.). Typical Stern magazine: when they decided to review the book, they asked me to go and photograph a few more people to illustrate the review.

JC: The project 100x100 brought you back to smaller scales, with photography of people’s apartments. How did you find the apartments/people?

MW: With 100x100, I attempted to answer one of the questions people repeatedly asked me when they looked at Architecture of Density: ‘how do people live in there?’ I had originally planned on shooting a series of 100 interiors in various buildings, a daunting task, as it is very difficult to access private space in Hong Kong. But as luck would have it, a friend of mine who works as a social worker brought my attention to the Shep Kip Mei housing project, which happens to be the oldest public housing project still standing in Hong Kong. This person took me on a tour, and at some point she remarked “did you know that all the rooms in these four buildings are exactly the same - each measures 10 x 10 feet, and the layout of all the rooms is exactly the same?” When I heard this, I had an epiphany and knew exactly how my new project would look like, and what I would call it. In this case, it was also a race against time - I was informed that I had one week to complete the series, as all the residents were moving into a new building at the end of the month. If you look at the calendars in the individual rooms, you can see that I took most of the images during three days in April 2006. In the 100x100 series, I was not so much interested in taking portraits the people who live there, but rather, showing how they live - how does one make use of so little space? The fact that all the rooms have exactly the same layout makes it easy to compare them - what objects do most rooms have in common, for instance (fridge, fan, clock, calendar.), each room has a series of ventilation slits in the upper back wall - obviously, the inhabitants did not like these and most covered them, each in his or her own way. So the series has some of the characteristics of a scientific project - an investigation into the use of limited space in Hong Kong.

JC: In a sense, even though your photography produces fine art, something that people can hang on their walls - especially the large-scale photos of those huge apartment blocks look fantastic big - your photography, to a large extent, is a social commentary about how people live. I find it interesting that the work of many contemporary photographers at least in part has a social or anthropological side to it. What are your thoughts about this?

MW: It’s in part ‘Zeitgeist,’ it just seems to be popular at the moment for museums to exhibit social commentary. As to why photographers are shooting the subject matter which they are, I guess it depends on the background of the individual photographer. I have a liberal, left-wing background: I grew up in Berkeley, California, in the 1960’s and studied photojournalism in Germany with Otto Steinert in the 1970’s - both had a tremendous influence on my development. One of the first series of photographs I ever took were of national guardsmen throwing tear gas at demonstrators standing in front of Sather gate on the UC Berkeley campus during the people’s park riots. My fist published photograph was a portrait of a policeman staring down a demonstrator in the magazine ‘SF Camera’ in 1970 or 71. So my photographic background is a photojournalistic/documentary one. My university thesis was an in-depth look at the living conditions of a coal miners town in the Ruhr area in Germany (on my website,) influenced by Eugene Smith’s ‘Minimata’ project. I spent 18 months photographing the town and its inhabitants.

I guess the next question would be: “how (and why) did you make the transition from photojournalism to art?”

Regretfully, my photography professor at the Folkwang university in Essen, Otto Steinert, gave us a very one-sided education - his strength was photojournalism, not art. The city of Cologne, however, was only a one hour train ride away, and I went there religiously to visit the famous art book store of Walter Koenig. And with each visit, I bought one book which struck my fancy: Ed Rusha’s small limited editions, William Eggleston, Lee Friedlander, Winograd, Richard Heinicken, Baldessari, Walter de Maria - Koenig had all the catalogues of all the contemporary shows, it was mind-boggling. It was here that the seeds to my artistic career were sown. The problem was, they were never nurtured, so it took a long time for them to bloom. Not once, for instance, did Otto Steinert discuss the new American color photography of the 1970Â’s with us - it was photojournalism all the way. Mind you, in the 1970Â’s, photojournalism was a great career choice: the magazine market was booming in Germany and the budgets were unlimited. I led an wonderful life, traveling all over the world for magazines shooting interesting topics, so there was little reason for me at the time to explore other directions. But this changed when I moved to Hong Kong in 1994. Although I was thrilled to be there, I had been working as a photojournalist for 20 years, and was starting to question the profession - might it not be possible to express my ideas in ways other than as double pages in a magazine? I began feeling confined by the demands of the art director - the marching order was: photograph in the style of Stern magazine, or the stories would not get published. And then in 1996, I brought back my first Bastard Chair from China, the beginning of a collection which would ultimately consist of more than 100 objects (see the bastard chair topic on my website). Parallel to collecting the chairs, I also started photographing them as objects. I called this a ‘project’ and concepted it as a book and exhibition. I presented the idea to Gerhard Steidl and he made a book out of it (Sitting in China), and then the Kestner Museum in Hannover, Germany, exhibited it - I was on my way to a career as an artist.

JC: All in all, your portrait of Hong Kong, with its immensely crammed huge apartment complexes, isn’t all that flattering for the city. Have people ever complained about this? What kind of reaction do you get in Honk Kong?

MW: The reactions I have had to HKFDBD by the Hong Kong people have been ambivalent - those who have traveled and have a cultural education usually can appreciate the images on an intellectual level, but their gut reaction is often “your images of Hong Kong are so ugly and dirty and not very favourable to us - can’t you find something beautiful to photograph?”. They are also very concerned about what these images reveal about themselves - laundry hanging out to dry for strangers to see and back alley improvisations are not their idea of a progressive and modern city. But for me, this unique vernacular culture is what makes Hong Kong a visually interesting place and gives it character, other than Singapore, for instance, which many Hong Kongers see as a role model. Singapore is for the most part a horribly boring city - its policy of urban renewal has in fact turned the city into one big shopping mall. This is happening in Hong Kong also - traditional Hong Kong neighborhoods are being torn down to make way for hotels, office buildings and shopping malls. Regretfully in Asia, progress is equated with tearing down the old and bringing in the new, so within 10 years, most of the traditional, older parts of the cites will have vanished. This is a great loss and will, I am sure, be one day deeply regretted by city planners.

JC: It is interesting you mention this, because I have run into the same kind of reaction quite often, both when talking about a photographer’s work (like about yours) or when talking about my own photography. I sometimes think that many people don’t even realize what kinds of environments they really live in until a photographer takes photos of them without applying the usual filters or without going for the usual stuff that you always get to see in tourists’ brochures. I guess this brings me back to the topic of social commentary. But there is also another aspect of this, namely how we can treat such work as fine art when in fact we are hanging photos in our galleries or living rooms that depict things that aren’t all that nice at all. I mean this kind of photography gets a treatment that, for example, a book that contains descriptions of the sad circumstances some people live in would never get. I have to admit I have a slight feeling of unease about this (even though I am way too hooked to this kind of photography - both as a viewer and producer - to stop dealing with it). What do you think about this?

MW: Does art always have to be nice? Or, to put it another way, why does the art we hang on our walls have to be nice? I would not necessarily hang a Hermann Nitzch photograph in my 9 year old son’s bedroom - he’d have nightmares - but the ‘art’ I hang in my living room is an eclectic mix - some humorous, some disturbing, some ‘just’ beautiful: Neo Rauch, Richard Misrach, two Han dynasty clay figures, a 100 year old Karen tribe Burmese lacquer tray, which looks like a Jasper Johns painting, a collage made of a piece of wood and two wine bottle corks made by my son, a photo of mine from the back door series, a pelican skull found on a beach in Northern California, a hand made sign I bought off of an unemployed man from of a factory in China, it says: “strong man, can work.” I like having a ‘Wunderkabinett’ at home - it’s entertaining for guests, lots to talk about. I have many conversations about my back door images - interestingly enough, quite a few people have come back to me and said that after looking through my book, they now see Hong Kong with totally different eyes Â- what they previously overlooked whilst walking around the city now caught their eye and made their city experience ‘richer.’ What more can an artist ask for?

P.S. Thank you Michael Schmidt for creating the magnificent body of work ‘Waffenruhe’ (truce). This book had a profound effect on the way I see things and inspired me to photograph Hong Kong in my own way.

By

By