A Conversation with Michael Schäfer

MORE IMAGES

The starting point for this work is the idea that at the base of every culture there is a pool of template narratives, which are told over and over again, just always with new protagonists and general contexts.

Images are in the news - not just literally, but also as a topic themselves. In a day and age where image manipulation has become very simple to do, hardly a day goes by without yet another “scandal” about some manipulated image somewhere. As I indicated on this site before, I think without a proper understanding how images work, this situation will not change. Introducing very unspecific - if not unrealistic - rules about the amount of manipulation that is acceptable totally misses the source of the problem. When Michael Schäfer sent me the link to his new work, I thought talking with him about his images and what they mean might be a good idea. Of course, here we have an artist, not a news photographer; but I see a lot of his work as a good way to start investigating how images work and how they are being used. (more)

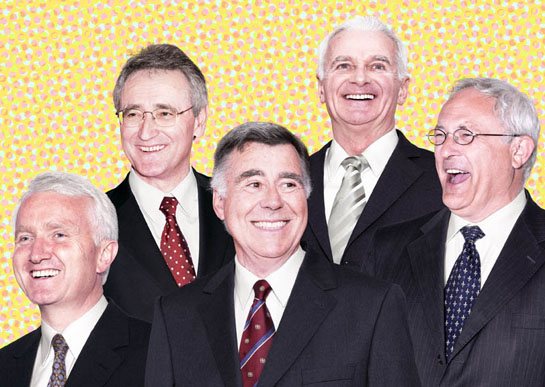

Jörg Colberg: The images in “Vorbilder” [“Role Models”] look oddly familiar - at least for someone following the German news, even though the faces of the actors aren’t. Can you talk a little bit about the series and its motivation?

Michael Schäfer: I guess I should first talk about the fabrication of these images - which always gives me a headache! - o.k. then: They are digital montages. They consist of a scanned and sometimes cropped image from a news magazine and of image parts that I photograph in my studio. In most cases these fragments of images I take show bodies or just heads of actors, who mimic persons depicted in the news picture. In the final montage they overlay the corresponding parts of the original scan. So by covering or masking the well-known politicians and managers with carefully staged actors, the images loose their actual context. It also becomes quite clear - at first glance - that these pictures are composed, staged and worked on. One can easily identify the difference between the coarse structure of the enlarged original magazine print and the more detailed photographic depiction of the parts I staged in my studio.

The starting point for this work is the idea that at the base of every culture there is a pool of template narratives, which are told over and over again, just always with new protagonists and general contexts. We can easily observe that by looking at bestsellers and blockbusters or the yellow press: “The good hero wins in the end”, “The rise and fall of the star”, etc.

As an interested reader of news I got aware that even “reputable” news coverage (“news stories”) is infected by these template narratives. When I say infected, I do not want to state that this is necessarily bad, but at first sight it seems to contradict matter-of-fact reporting and thus might be considered as problematic. This system of circulating template narratives however seems also to constitute the format we use to comprehend and classify whatever information we consume.

The news about politics and economics often transport tales of power. They contain subject matters like rivalry, triumph, backstabbing, victory, defeat or decline. So this is the background for the images I am interested in. In general I don’t like pictures that are too clear cut and prefer a certain amount of ambiguity that holds my attention.

JC: Would you say that what you call “template narratives” is also something that is generated by photographers themselves, for example when thinking of photojournalists?

MS: It is certainly something they react to. Means they think within culturally given narrative structures. But if they would not do so, they would probably not be paid, the pictures would not be printed and if, they would not be understood - and all of that happens to a lot of talented photographers. Don’t get me wrong. This critique is not aimed at photographic images in the media. I simply try to describe how deeply our culture and with that communication is rooted in perpetual, codified storytelling and that it might be interesting to have a closer look at that. Just above I was using such a template: The talented …photographer/writer/painter… that is not understood, is not heard and poor. Maybe there is a more intelligent way to look at it…?

JC: Any idea what such an intelligent way could be, and how we, as a modern society, could get to it?

MS: I was referring to my little naive story. As an artist I try to work with evidence, which I find in the media - evidence about how the discourse of power is being played in a capitalist democratic society. I am looking at emotionally charged images since they exhibit those underlying narrative patterns, which means here we are looking at the real theatre of our society. It blurs with entertainment but is far more serious, it is emotional and different from reason. It seems like an irony that images, which appear somehow ambitious to give a glance behind the scenes, involuntarily play and affirm the game of the spectacle.

JC: “Pressebilder” [“Media images”] seems to work in very similar ways - you’re constructing media images, using hired actors. What are the differences between this series and “Vorbilder”?

MS: The “Pressebilder” are replacing the original news pictures they are modeled on across the entire picture plane. They are - in terms of their construction - much more sublime than the later pictures. At that time I was very much focused on reproducing certain details and gestures in the images that had puzzled or struck me. Restaging an image is always an intense journey into the sudden complexity of its details - where one can get lost in. Also by erasing every trace of the original images I had the feeling to lose too much of that maintained evidence that news pictures are scented with. So with the newer pictures I am much closer to what I intend to do - and the work process is much more economic which I really like.

JC: It seems like both works are very conceptual, and the newer work just managed to realize better what you were after. I find it interesting to see you describe “Pressebilder” as being more sublime, because a casual viewer will probably miss all the nuances. That makes conceptual a bit of a hard area to work in, given that not only do you have to worry about getting the work right, you also have to worry about people missing what you’re after. Are you concerned about this?

MS: Sometimes it is good when people miss what you are after…

Well, I think there are always different ideas at stake when I work at something and sometimes they even conflict with each other. Let’s say I got bored with the notion: “At first sight this picture looks normal but when you look closer you see it is not”. And then it was somehow like crossing a border: Moving away from images that still look like a photograph yet are composed digitally from several images to images that obviously look like a montage was like giving up something precious and at the same time liberating.

JC: Both works seem to reflect a general mistrust in images in the media, or maybe more accurately how images are used in the media. We can’t, however, just do away with the media, or treat all images as outright lies - because a functioning democracy is hard to imagine without functioning media. How should we approach images used in the media?

MS: I totally agree with you. Media images are important - maybe too important for us to be satisfied with that very limited visual vocabulary that is generally used. And I would find it redundant to say that technical images are lies. They are subject to speculation.

Given the context they are placed in, we read them as information and thus it is our responsibility to decide if we want to give them credibility or what to make out of them. To give an example how impossible it is to judge an image: In 2004, Josef Ackermann, a powerful bank manager in Germany, was accused of breach of trust in a scandal around unlawful compensation payments for top-managers. During a trial break in the court house he was photographed by a reporter openly smiling giving a victory sign. This picture quickly was published all over and stirred up a storm of indignation. Until today it is a symbol for the arrogance of the social elite. Ackermann stated later that he did not want to provoke with this gesture. When another manager during that court break had mentioned the trial of Michael Jackson he had just spontaneously imitated the gesture of the pop star greeting his fans. Well, we don’t know if that is true. But one could also subtitle the image with: Ackermann loves Michael Jackson. How nice!

JC: What can we do, though, to get around these kinds of issues? It seems to me that the media are gravitating more and more towards the sensationalist, and Ackermann flashing the victory sign is just too tempting an image for a newspaper to re-print. However, even though viewers on the one hand distrust images to an extent that almost every newspaper image is seen as a potential lie, there doesn’t seem to be much of a change towards thinking about not whether images are “true” or not, but about how they are used and presented. Is this part of the idea behind your work, to make people ask these questions?

MS: It is always good to know if a picture in the media is manipulated or not and it is interesting to analyze how it is put in context. Information has to be questioned, that’s a given - and a good debate. However in my work I am not too concerned with that. I am predominantly interested in the grammar and fragments of narrative of images. Within the gallery my pictures unfold their own ambiguities and react to that context. They do not show how they were used in the media but still they point towards their origins. By giving titles to the images I suggest a vague interpretation, knowing that the onlooker knows that this is an artistic positing. In the gallery we expect to be deluded, to be led on a terrain with traps, dead ends, false information and so on. In the news we want to rely on what we see.

JC: But it seems to me that learning something about how images work and what their narratives are in a gallery setting and then forgetting about it once you’re outside of the gallery… I somehow think there has go to be a real connection made?

MS: What I talk about are the different contexts. Take advertising: Images in advertising have a different status than images in the news. If I understand you right you are saying that a work of art might point to the contextualization of technical images within the media. Well, why not?

JC: Exactly, why not? After all, artists are embedded in the “real world,” even though people often think that art is art (and thus artificial and not real), whereas the real world has to do with the facts. I take it you don’t see your work necessarily as a commentary that extends beyond the art world?

MS: When I restage pictures from the press it is to throw some questions of mine into the discourse about images and I comment on society at the same time. I just think my work does not address the very issue that you seem to be concerned with. Some of my recent pictures are currently shown at the Museum for Photography in Braunschweig, Germany. The exhibition combines works about news images of five artists and a large number of newspaper front pages, alone 70 different ones of September 12th and 13th, 2001. So to answer your question regarding planet art: I am very lucky and satisfied that my work can be part of such an exhibition, which takes a close and critical look at images in newspapers and addresses a larger audience.

JC: “Les acteurs” investigates portraiture, by showing students of a German High School posing as (future) successful business people. I’m tempted to see “Les acteurs” as a counter point of sorts of Thomas Ruff’s portraits, where the artist asked the subject to refrain from striking any kind of pose. The results, however, are oddly similar: In both cases, we are left getting “generic” portraits, where what we see tells us almost nothing about the subjects. To what extent did you create “Les acteurs” as a commentary on portraiture and what we read into it in general?

MS: My initial idea was to portray gestures of representation and I was not sure how this project would develop. As I photographed the students I asked them during the sitting several times to look at the already taken images on my computer so they could alter their poses until they were satisfied with their image. I figured that they were adjusting their poses to those they might have seen on photographs of their parents or grandparents. So I agree (again), these images tell us much less about these kids than some people might want to read into them. But they give some indications of how gestures are learned, appropriated and used to express social standing. The experiment shows how uncritically and easily these privileged teenagers fall back to handed down postures since they have not developed any genuine bodily expressions of their own to claim their future place in society. It also seems as if these gestures might have the function to mask insecurity.

When I sometimes refer to “Les acteurs” as a portrait series then this is not entirely correct. As I mentioned earlier I was interested in gestures and this is how I would like to see these images: They are depictions of gestures. The bodies of the kids could be referred to as the medium for the gestures because these gestures have a life of their own as latent images - they are already some kind of immaterial image. They only surface, are only staged for the sake of their representation on pictures through which they reproduce or circulate. If I would describe the work “Les acteurs” in terms of portraiture, I would prefer it to be regarded as a specific portrait of socialization.

Q: In general, I’m curious how you place your work into the general context of German photography (whatever that might actually be - feel free to define it yourself)?

A: Honestly I am not sure if I could give a satisfying answer. Certainly there are some big names like Thomas Demand or Peter Piller which would give a broad context. More interesting regarding the “Vorbilder” is my encounter with a young painter from Leipzig years ago as I was sitting for him: Steven Black paints mostly friends in his studio. He does not bother to fill the whole canvas with paint but the area of his most interest, the face, is almost as thick as a relief.

By

By