A Conversation with CPC 2012 Winner Karen Miranda Rivadeneira

Juror Michel Millard picked Karen Miranda Rivadeneira’s Other Stories/Historias Bravas as a winner of the Conscientious Portfolio Competition 2012, writing The images which have touched me and attracted me the most are Karen Miranda Rivadeneira’s. I found this series of images very interesting as they are a touching mix of reportage meets fiction meets mise en scene. They are very human as they deal with big general themes such as life, childhood, adolescence, motherhood, death, and at the same time with details and particularities. They are exotic and very personal. I like that the photographic approach is not overstated, it is precise but very simple. Every frame is filled with humanity. I’d like to see many more of them. In the following conversation, I spoke with the photographer about her work. (more)

Jörg Colberg: Let’s start with a very simple question first - what makes a good photograph?

Karen Miranda Rivadeneira: A good photograph? When it leaves me with no words or not even a desire to understand or wonder what the photographer wants to say, when instead of rising my curiosity it leaves me in complete awe.

JC: You write that Other Stories investigates “the role of photography and its relationship to memory.” Later, you speak of truthfulness. Given that memories are notoriously unreliable, at the end of the day when you create photographs aren’t you creating memories?

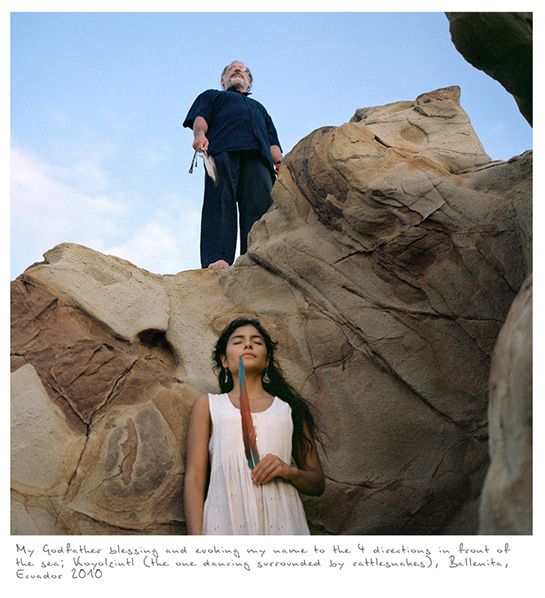

KMR: In Other Stories, I was interested in searching my mind for the events that really seemed significant to me. But how could I find those events? Since memory changes every time we “remember,” my conclusion was that in order to find these events I must search in the areas of my mind not even I had access to. So I decided to get some help and talk to my relatives. That is how Other Stories began. In the end, we don’t need a photograph to create a memory, we do that all the time, night and day. My intention with Other Stories was to freeze a personal story as accurately as I could in one shot. That way, we relived the emotion, so it ends up been a picture of an experience and how the experience shaped my understanding of life.

JC: I’m curious about the process that goes into making these photographs, in particular since they involve your family. How do you go about making a photograph? Do you tell your family members exactly what to do?

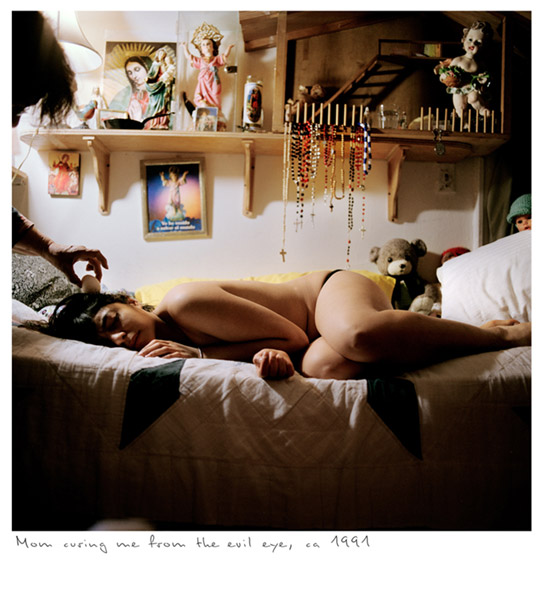

KMR: In the beginning, I thought of doing some type of auto-hypnosis in order to go to my earliest memory. However, this did not work. Neither did thinking a chronological order. My family, in particular my mother, aunt and grandma, had a better idea of the events I wanted to bring back. So we talked about them. For example, with Evil Eye, I remembered my mother cleansing me with an egg once. But in fact, as we were talking about the experience she told me she would cleanse me quite often. This changed things. I thought of a mother that would “try out” a ritual, but now I know of a mother that comes from a lineage of women who do and belief in this ritual. Every image was sketched before it was set up. So I did not really tell them what to do. Right from the beginning it became a collaborative project. I could have never done it this way if it wasn’t for their input and observations.

JC: Given you had help from your relatives, do you view the images as your memories or more like collective memories - collective memories that, in effect, are cultural memories, stretching back in time through tradition?

KMR: In the act of sharing a memory, the memory becomes part of someone else’s (collective) memory; we unconsciously live the story, and what is even more interesting we go through our “data” of memories and try to find events that resemble the one we just heard or saw. This is what we do all the time. For me, Other Stories is personal but is also very collective.

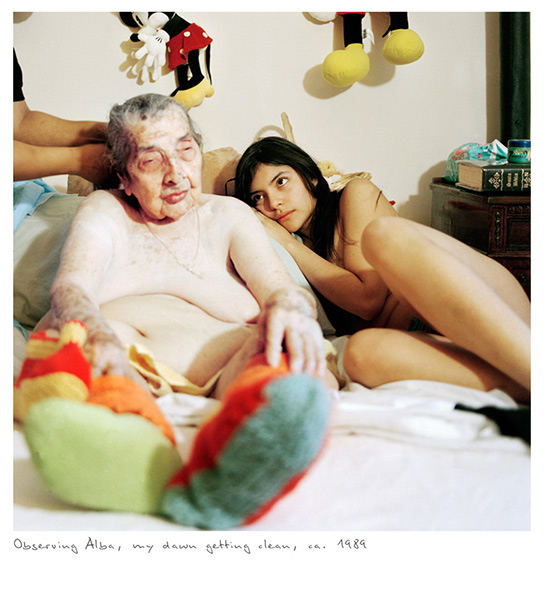

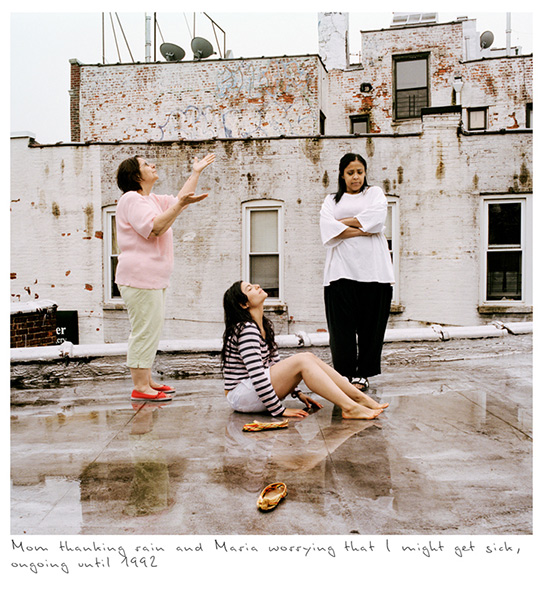

JC: Your photographs come with captions that explain the photographs or talk about what can be seen in them. I’m curious about the reasons for the captions - would the photographs not work without?

KMR: A lot of people wonder about the captions. I’ll tell you. The captions work like Polaroids in a family album, where there is always a short text at the bottom of a picture. It makes sense to the people involve in the image, and I wanted this work to have that personal-story structure. I never wanted to be too specific, neither too poetic. I wanted the captions just to say what is happening in an objective and subjective way, a bit like directing the attention of the viewer to what the memory is about and from there they can work their way around.

JC: … as if to make sure the photograph “shows” exactly what you want it to show?

KMR: More a way of narrowing down the possibilities of what the photograph could be about.

JC: You mention your bi-cultural upbringing. Can you talk about the influences this has had on your photography?

KMR: Growing up, my dad traveled a lot through Ecuador, Peru and Colombia. We traveled by land. I was often crossing borders and seeing different ways of living. There is a huge divide in how the indigenous people of the mountains live in contrast with the people at the coast. I have always felt that people seemed very marginalized even from themselves. But at the same time there was something that was common in everyone, everywhere we went.

A lot of times life is about relating to the experiences of others. Later, I traveled to the US and realized it was the same scenario. We all look for points of connection. The trick is to find where they are and what they connect.

JC: In different countries, we might have different ways of connecting or relating to other people, which offers opportunities for artists as well as risks: As an artist, one can hope to expand people’s idea of what it means to connect to people, while, at the same time, there are much more chances for misunderstandings. What is your approach to this complex?

KMR: It seems that when I get the most intimate with my photography, somehow it becomes even more universal. I think the secret is to share from a place deeper than culture, background, ideology - share from sheer emotions and experiences that we all have, and then we can all (somehow) empathize.

By

By