A Conversation with Juliana Beasley

There are few things that are subtle in Juliana Beasley’s photography. But then, the fact that you don’t get to see stuff like that too often in our somewhat sanitized culture doesn’t mean that you’re looking at the fringes (as much as many people would like to believe that). I talked with Juliana about her work.

Jörg Colberg: In some of your series, you are dealing with topics that are usually covered in quite convoluted ways - if at all. Billions of dollars are yearly made in what one could call the sex industry, yet nobody ever really talks about it. The situation of people with mental illnesses is even worse. The only nice treatment they typically get from our society is that we now call them “mentally challenged”, and we really only allow them into our living rooms if they’re scientists, say, for whom the combination of genius and mental challenges can be transformed into a soppy story, to be digested in 90 Hollywood minutes. I cannot imagine that covering these issues is straightforward. How do you go about projects like “Lapdancer” or “Rockaways”?

Juliana Beasley: I see the way that I photograph as being straightforward with a little touch of experimentation and probably a lot more chance and a bit of unconscious behavior. That which happens around me and that which I capture with the camera, I hope, is more free flowing and hopefully as complex as the subjects whom I photograph.

My work on Lapdancer emerged from my own experience working as a career stripper. In 1992, a couple of years after I graduated from NYU with a degree in photography, I started working as a lap dancer in NYC clubs. I needed money simply because I wanted to travel abroad and work on my documentary portfolio. Shortly after, I realized that I could make enough money to pack away for the future and began dancing full time.

My newfound career was full of absurdity and human malaise. I was intrigued with the adventure of what seemed like Disney-like amusement park for adults, and one, which did not include any of my circles of friends and acquaintances. I felt the urge to document the landscape and my experience.

I suppose at first I came to photographing the subject from a voyeuristic angle. I also was and am deeply influenced by the honest, down and out books by Larry Clark. I thought, “Hey, my work life is as surreptitious and as rank as Mr. Clark’s.” I liked the adventure of not doing the straight and narrow and existing within a subculture. The dancing was cathartic.

At first, I used to carry my Contax T2 in my duffle bag, stashed amongst all my lingerie and schoolgirl plaid skirts. I figured if it got stolen out of my bag that was the chance that I would have to take. Later, I began to photograph with a Contax SLR with a Vivitar Flash on-board.

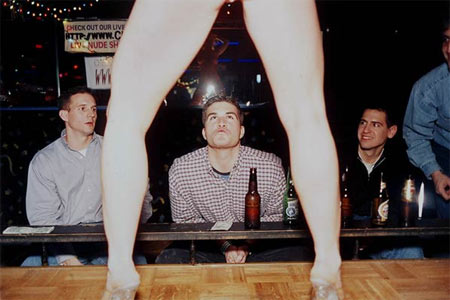

One night, I came into one of the clubs on my night off, out in New Jersey, and asked the manager if I could photograph a dancer on stage. I knew this could be a wonderful ploy to begin getting the expressions of the customers’ faces in the shots. Over the eight years of dancing, I went from photographing the dancers in the dressing room to finally, getting the chutzpah to ask customers in the club if I could get them in the shots at the stage.

I was actually for the first time playing myself, the photographer, at the job where I could play anything but myself. There were customers who refused to be in the photographed for the obvious reasons, but there were also other men who were very excited and zealous to hear that they would possibly be in a published book.

The book also includes my own writing and interviews that I did with customers and dancers. I felt that it was important for the subjects themselves to speak about their interpersonal relationships with one another. As a witness to these interviews, I too was an insider of an often-misunderstood milieu. I wanted to make an ethnographic book based upon the untainted and least subjective viewpoints as possible.

The last two years of my stripping career, I did not work to earn money but traveled as a free agent to Vegas, Florida and Colorado to complete the book. In one club the management made a deal with me - I had to work if I wanted to photograph. It was an impossible situation. I would finish a 20 minute dance set on stage, run to the dressing room, pull out my camera, flash and quantum battery. I clipped the quantum to my g-string and literally, it was half falling down from the weight of the battery.

Once, I began editing the photographs, I became clear as to what the project was about and how I wanted to conceptualize the book. I knew I did not want to make a book like so many I had seen, which explored the lives of the strippers outside of the clubs. This was in part because I thought this theme was overdone and often, the dancers were misrepresented as a cast of victims or oversexed whores.

I feel that many of these biases stem, in part, from a puritanical view that women working in the sex industry partake in disreputable deeds for the simplistic reason of poor morals or because of a past, gone bad. After dancing for close to eight years, I realized that there are many motives behind why women and myself, included, choose to strip. And there are reasons why men become customers. I decided to focus on the exchange of love and affection for money - “love for sale.”

Strip clubs can feel like a microcosm of our contemporary society. Many people often feel alienated and discontent whether they have achieved material gain or not. Our desire to consume fantasies can begin, for example, with turning the page of a fashion magazine or watching the latest reality show. It either boosts our self-esteems or leaves us with feelings of rejection.

The desire to belong and have physical contact is universal. In this day and age we are more isolated than ever. Many of the men whom I photographed and interviewed feel socially cut off and search for physical contact. Many spend their days working behind a computer and come home to eat their delivered meals alone in front of the television. Other customers in the clubs were in marriages, lacking emotional intimacy and not because it was impossible to nurture between the two. Instead, the customers searched for a make-believe relationship with a stripper who represented everything physically desirable in our Hollywood-centric country or as one customer told me, he was looking for a dancer who looked like Pam Anderson.

JC: How about “Rockaway”? How did you come up with that project?

JB: The Rockaways project just happened. In 2002, I went there with a friend and her girlfriend who was writing a book on recreational areas in New York City. We walked up onto the boardwalk and immediately, I heard a ruckus coming from a local bar. When I noticed a bartender leap over the counter with a bat in his hand chasing a difficult and swearing customer away, I knew I had arrived. I felt immediately at home.

The following week, I showed up with my camera and began photographing a local homeless woman who amazed me with her will to survive despite her never-ending consumption of cheap and potent beer. At first, she darted back and forth in front of my camera, and soon we became friends. She doesn’t trust people easily because she suffers from schizophrenia and sub exists pretty much on beer alone. The project just evolved naturally. Through this one woman, I met one drinking buddy and then the circle just grew larger. Rockaways, is simply not about alcoholics and mental illness, it is more about giving dignity and a face to people who are often skirted to the side and invisible in the world. The Rockaways is a located on a peninsula far and out of sight to most people living in NYC.

JC: I have the feeling that it most be hard to promote these projects. Unlike in England, say, where this kind of photography is quite a bit more common, the directness and harshness of your photos is not what you get to see a lot in the United States, and especially not about sex or mental illness combined with poverty. And as you told me earlier, people will not easily hang these photos over their fireplaces. So how do you promote them?

JB: I try to remain honest about the projects, the people in the project, and my own part in it. If I want to show people in a compassionate and truthful way, I feel I owe it to my audience to do be honest about myself. That is why in Lapdancer, I wrote about myself in a way which people have told me is brutally honest. I made myself vulnerable to my audience and it was personally therapeutic.

Reality is hard on everybody; that is why fantasy is so appealing. Fantasy is a mutual tie between Lapdancer and the Rockaways project. The alcoholics and the mentally ill in the Rockaways have not yet sobered up to the reality that the same bottle that feeds them is the same that is destroying their minds and bodies. Their addictions deceive them with delusion and dysfunction. In Lapdancer, the customers and dancers coexist in a covert environment where their addictive patterns to find intimacy are nothing more than a manifestation of a consumerist culture built on the have and have nots. Both documentaries are about the desperate human desire to connect to others and how people often look in the wrong places for affection and compassion.

These are both important issues and yet, many people don’t want to look within or outside of themselves at these difficult circumstances that affect all of our lives on a personal and spiritual level. I believe that it is more frightening to look at our own destructive patterns than to look at others.

People have told me that my work is gritty, courageous, and brutal. Perhaps, compared to glossy fashion magazines this is true. Once an editor at a popular news magazine told me my work was too painful and perhaps, I should be taking portraits of my friends to put in my portfolio. This is a magazine that publishes photographs of horrific imagery from wars around the world and puts them on the cover. At times it feels frustrating trying to promote my work. And yes, it is hard.

I have had and believe I will have a more accepting audience in Europe. There are just fewer and fewer magazines presenting the documentary photo essay and less so in the United States. There are people, however, here in the states who find my latest work intriguing. I always feel excited when I meet someone who can look beyond the voyeuristic nature of a book like Lapdancer and the Rockaways project and who see it more as social commentary.

Recently, I put up my web site and I got so many positive responses. In particular, one British photographer has offered so much support and advice since he has seen my work on my site. I also found that contacting other photographers or meeting with editors has led me to other wonderful opportunities. I’m moved when other photographers reach out to help me since the business can be very competitive.

JC: I’m always a bit struck by similarities, and sometimes I see them where most other people don’t see them - which probably indicate that there aren’t any. But when looking at the Rockaways series I thought of some of the photos taken by Diane Arbus. Obviously, the style of photography is a bit different, but then it’s a different time, and photography has evolved a bit. But if you ignore those technical differences, I think your Rockaways series has quite a few similarities with Diane Arbus’ work. She became famous (or notorious if you will) for taking photos of “freaks”, and if you make the effort to find out why she took those photos, then you find that it’s not some sort of morbid curiously, but a deep inner conviction that “freaks” are people just like us, with just some superficial differences. Is there a similar motivation behind your work?

JB: I hate the word “freaks” or for that matter “crazy”. I don’t want to be judged, and certainly, I try not to judge others regardless of the differences I might have with someone. Underneath all of our cognitive training, physical and mental outer coats we are all connected by universal similarities. When you sit in a roomful of old, vulgar-speaking, angry men and you watch them break down and cry, telling stories about the dogs they once had in their lives and how they died, you understand the depth of desire to be interconnected.

JC: The photographs of your subjects strike me as incredibly open. There really is nothing hidden, and the viewer gets to see an unsanitized view. I imagine there must be a lot of trust between you as the photographer and your subjects, be they lap dancers, their clients, or the people from the Rockaways whose photos you took. How do you develop that kind of trust?

JB: I learned some social skills during my dancing career. I learned that people like to feel cared for and loved and so do I. So, I try to treat people the same way. I remember when one of the men I photographed out in the Rockaways walked me to the subway station how terribly he stank of alcohol and poor body hygiene. His eyes were full of puss and he could barely walk because he was very drunk. When we parted, I gave him a hug, and that’s because I care about him. I know if I were at a deep low, as he was in that moment, I would have needed a hug too. Many people suffer, because they don’t receive physical comfort.

When I was little, I grew up around hospitals. My mother was a neurologist and often would get called into the hospital in the middle of the night because of an emergency. While I was waiting for her in the intensive care units, I would sit around and watch the patients on stretchers. Part of me was frightened with what I was seeing and yet, I had so much curiosity to know about what had happened to the people lying in beds.

I met many of my mother’s patients in her private office and saw her smile with so much pride when they made small improvements. Once, one of her young patients could brace herself up spastically against a wall and walk a couple of feet. My mother applauded, hugged her and ran for a lollypop to offer to her. I believe both of my parents influenced me in how to respect others who are seemingly different from what we call the “norm”.

So, in terms of trust, I just like to meet people who do things a little differently. I feel a familiar feeling when I’m in those situations. And I like to make people, often marginalized, for whatever reason, to feel whole and connected.

JC: Do you ever feel like you’re intruding into people’s lives? How do you determine the boundary between what you fell you can show and what you cannot show?

JB: Of course, there are times when I feel like I’m intruding. But, I feel, mostly, like a witness or a dinner guest who never left and was asked to stay over a night or two. I think everyone has their own moral agenda of what they will and will not photograph. For example, one night, I was hanging out with some of the guys at Paddy’s house in the Rockaways. One of them, John Trainer, fell to the side and began convulsing and having a seizure as result of his chronic alcoholism. I put my camera down, put a pillow under his head and basically had to direct a room full of drunken men over sixty on what to do to help me until the paramedics arrived.

There is a necessity in showing the aftermath and trauma left behind after battle. When Katrina occurred, the media focused on the drama of a so-called natural disaster - a year later, no one seems to report on what has become of New Orleans and its inhabitants. I see the importance of photographing and writing about the consequences of the war, whether it is violence against one another or self-destructive behaviors. I pick up my camera after the bullets fly and photograph that which remains.

By

By