A Conversation with Jerry Spagnoli

The other day, I had the chance to visit Jerry Spagnoli’s studio and to talk to him about his work, and afterwards I asked him whether he would be available for a conversation, to be published on this blog. I’m very glad he agreed to it.

Jörg Colberg: There probably is only a small number of photographers who have produced such a diverse range of work as you. Your works ranges from Daguerreotypes and more traditional b/w work to extreme and abstract enlargements of negatives and wide-angle colour photographs that use a large amount of digital post-processing. Can you talk a little bit about how this all evolved? How does one jump from mercury vapours on metal plates to pigment prints based on images in a computer - mirroring the evolution of photography itself?

Jerry Spagnoli: For me the photograph is a way of conveying ideas. I’m not driven by pictorial considerations when making decisions about what to photograph and how. I select a particular method, or technique based on how it will contribute to the content of the series I’m working on. Of course the look of the work is important and a lot of decisions are made to arrive at the image I visualize in my head but the visual effect of the picture always has to be in the service of the idea. This is a conventional way of operating in art. Sculpture theory, literary theory, film theory have all been built around this approach, basically form and content have to operate together to convey ideas.

A fundamental reason I use photography in my work is to exploit its apparent simple transmission of facts, its objectivity. We all know that photographs lie, actually, to put it more accurately, photographs tell tales. In our daily life we take our experience of the world as objective, neutral, and trustworthy but of course everything we experience is heavily mediated by our training, past experiences and patterns of thought. We structure our lives by the stories we use to give meaning to what would otherwise be a chaos of information. It’s this experience of the world as an endless matrix of individual narratives that I am trying to get at with my work. Using different photographic technologies allows me to approach it from different angles.

JC: It is interesting that you’re stressing the art aspect here. Even though contemporary photography clearly has arrived at being a component of the modern-art world, I sometimes think that many people are not aware of what that really means, so they still approach photography as something that is foremost documentary. After all, when you go to Chelsea, many galleries either show photography or everything else - so there still appears to be some sort of division where, in fact, there should be no such thing. What is your impression of this?

JS: A: I think there are a number of factors at play. Photo galleries cultivated the distinction between photography and art for their own marketing reasons. They considered the separation useful to distinguish themselves from the larger number of art galleries and to attract clients who were specifically interested in photography. From the technical side, photography is so easily accessible as a creative medium that a lot of people pick it up and start using it without any regard for its relationship to the larger field of contemporary art. It’s easy to make a photograph and that ease encourages superficiality. Photography, for many people, is simply a convenient way to record a situation; and to a large extent the success of the photograph hinges entirely on how interesting the subject is. The medium itself is invisible. There are actually a number of theoretical frameworks that are currently being employed in photography, and the documentary approach is just one of them. However, there isn’t much discussion about the various aspects of photography, so naive work hangs alongside sophisticated work, and the distinction is not drawing critical response. This confuses the public and obstructs the kind of dialogue between photographers, critics and the audience that could stimulate the whole field.

JC: I’m wondering whether having such a wide range of work confuses people when they think about the photographer Jerry Spagnoli? Is that something you have to be worried about? Or is the variety your signature style?

JS: I think it could be a little problematic for people who don’t get what the work is about. I hope that using all these methods will cause people to think harder about what I’m up to so in fact the initial confusion could lead to a deeper understanding. It is worth saying however that the reason I use one technique or another is the inevitable consequence of the particular line of reasoning that I am engaged with. I don’t do one thing or another just to be different. Each step seems inevitable to me as I’m making it.

JC: What is the appeal of daguerreotypes? Why deal with toxic vapours and plates that can only be used for a short period of time? What attracts you to daguerreotypes? What is it you can show with daguerreotypes that you can’t do with film-based or digital photography?

JS: Daguerreotypes are, for me, a perfect form of photography. The image is preserved on a polished sheet of silver, a front surface mirror, which is an optical device. This optical characteristic of the medium is the reason for it’s uncanny presence; it’s ability to present the subject as “the thing itself”. It presents the subject with such a sense of real space and volume that the viewer can be momentarily persuade that they are looking through a window at something real. This is the ultimate demonstration of photography’s claim to objectivity but at the same time there are so many indicators embedded in the image that belie this apparent truthfulness (short depth of field, motion blurs, technical artifacts) that for me it is the perfect expression of the objective and subjective construction of the world in one simple image. You can approach this kind of thing with other mediums but the daguerreotype has it as a birth right.

JC: With a daguerreotype basically being a little mirror that you have hold in front of yourself, such a photo also appears to invite a more intimate relationship between the viewer and the object - quite unlike a photo that you can hang on the wall, and you can then look at it while many other people do the same. Does this constitute part of the attraction of a daguerreotype for you?

JS: The intimacy a viewer experiences with a daguerreotype helps to create the psychological effect I described above. There is the feeling that you are being let in on a secret when you look at a daguerreotype and that intimacy contributes to your confidence in the image, you feel like you have a personal relationship with it. The series I’m working on (“The Last Great Daguerreian Survey of the Twentieth Century”) is really designed to be seen by an audience in the future. These are private historical documents which are meant to convey my personal impression of the current moment. When someone 100 years from now looks at these images I want them to feel that they are engaged with something personal as well as historical. Daguerreotypes are perfect for that.

JC: I think your Photomicrograph series and Thomas Ruff’s jpegs might be related: They both expose the inherent limitations of the technology - film grain in your case, and digital artifacts in Ruff’s - to then show how those limitations can be used to create meaningful and extremely interesting imagery. Do you see such a connection? And how did you get interested in using a microscope to look at the patterns formed by the crystals on the film base?

JS: I think Ruff is trying to get at the way the mass media generates images and we in turn take them in. What I’m driving at is the fact that our minds are machines for manufacturing meaning out of the disordered material of the world. Mass media or not we are inevitably telling ourselves stories in order to make sense of things.

I started using a microscope to make enlargements of portions of my negatives when I realized that I had reached the limits of my enlarger’s optical system. I had been been photographing on the street and enlarging small ares of the negative (1/8 - 1/4 inch square) in order to de-contextualize certain details; to set them free from the real situation. In one image there were a bunch of policemen on top of the Federal Building in San Francisco who were tracking an antiwar protest. They were so far away that in the negative each figure was made up of maybe 100 grains of silver but you could clearly tell by their posture exactly what was going through their mind (to be fair they might have all been thinking about picking up groceries on the way home but to anybody looking at their gestures…) So I became interested in just how little information it took to communicate ideas through gestures. Our brains have an incredible facility for that sort of reading and I wanted to use this series to tap into that.

JC: Your latest series, Local Stories, employs a combination of unusual techniques - in particular photos centered on the Sun (instead of pointing the camera away from it) and digital manipulation of the images. How did you find this approach, and what do you want to show with it?

JS: Arriving at its current state took a few steps. I had been making daguerreotypes with references to contemporary history and decided that I wanted broaden the project. Daguerreotypes are small intimate images and one of the things I wanted to do was produce images which would have a more emphatic presence on the wall so naturally I decided to make big color prints. In order to maintain the quality of light in the image I chose 8x10 color negative film as the medium. I had been using backlighting with my daguerreotype project and for this new series I decided that I would put the sun in the center of the image. Now the sun in the middle of the image then required unconventional optics. I knew from experience that a pinhole lens responds in interesting ways to that kind of lighting so I went with that. I wanted a super-wide angle view of the scenes I would shoot so I built a shallow box camera. As I began working with this arrangement I began to see a strong relationship between the images I was producing and the work of the Hudson River School from the nineteenth century. This idea worked for me so I went with it. I also noticed some interesting structural resemblances between the camera and and a model of the universe offered by an ancient Greek philosopher and that contributed to the series as well and then the resemblance between the camera, this ancient universe and the Pantheon in Rome struck me and it became the Pantheon series (more information regarding these points can be found on my website). When I first tried to print the negatives from this series I discovered that the lighting created way to much contrast for the prints to be made with a conventional darkroom. The only way to get the print quality I wanted was to scan the negatives and put them into Photoshop where I could control all the aspects of contrast and saturation in a methodical way and output a print that matched my original intentions. I liked the fact that I was using a pinhole lens, the earliest of all lens, ancient in fact, to record the scene and I was using digital technology to make the prints. I was effectively book-ending the medium, using a pre-photographic lens to shoot the scene and a post photographic technology to make the print, not as a stunt but simply because there was no other way to get the image I wanted.

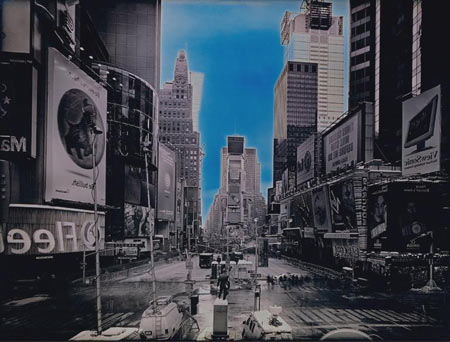

In 2007 I was working in Paris for a couple of months and while I was there I had many occasions to visit the Louvre. I particularly liked the gallery with all the history paintings, huge canvasses telling stories of great events, and I realized that I wanted to do something more like that, but to get to that look I couldn’t use a pinhole anymore, the exposures were to long to stop people who were even reasonably still, and the resolution of the lens wouldn’t support enlargements to the scale I had in mind. I did some research and came up with a lens of approximately the same focal length and was also designed to deal with the kind of difficult lighting I was using. I mounted it to my camera and began working. The change in the lens opened all sorts of possibilities. I could now shoot street scenes in which some of the people were sharp and the 8x10 film had enough resolution to render their faces with great detail. I realized that I was able to photograph large scale scenes and could also have intimate portraits embedded in them. Effectively this series combines the historical documentation of the daguerreotype project with the print scale of the Pantheon series plus the added advantage of shorter exposure times. My original thoughts on this project were that they would be historical documents of everyday scenes in the places that I happened to be. I was hoping to get at the thought that history isn’t the great events reported in the papers or in books but was in fact contained in the everyday experience of all the individuals everywhere in the world (it’s a tall order but there you go). I’d like the series to have a range of locations. Hopefully I’ll be able to cultivate enough opportunities to travel so that it will have the feel of a broad survey. I wanted to name the series so I looked into some of the writings from the Postmodern era that dealt with breaking down the Grand Historical Narrative, or the Meta-Narrative as it was also called and Lyotard proposed “petit ecrits” as an alternative. I translated it as Local Stories so that’s the name now.

JC: I noted that the Local Stories are printed very large. What is the reason for the large size? How do you determine print sizes in general?

JS: The prints are large in order to properly display all the information in the scene. When I make daguerreotypes there are a lot of interesting things going on, but without a magnifying glass most viewers will miss them. With big prints that sort of detail is readily available. Another consideration is that when you put a show up in a gallery space you want to create an impact on the viewer even from a great distance. You want to activate the space. Large color prints can

do that. Also with large prints you extend the viewing distance so that the audience can stand back and see a set of images at one time and still get quite a lot of information from each. I think this comprehensive view can contributes to the point I’m trying to make with this latest series.

By

By