A Conversation with Jeff Brouws

Jeff Brouws’ book Approaching Nowhere had long been on my list of books to buy, and I finally bought it. It’s a fascinating book, not just for the photography alone. There are essays at the end of the book about what is depicted, and I contacted Jeff to ask him whether he would be willing to talk about his work.

Jörg Colberg: A bit more than ten years ago, James Howard Kunstler wrote a book called Geography of Nowhere, which describes America’s move towards a culture based on cars and suburbs. The “Nowhere” from that book again appears in the title of your most recent book, Approaching Nowhere

. Do you see your work as a continuation of Kunstler’s work, using other means - images instead of words?

Jeff Brouws: I think his philosophy informs a portion of my photography re: that related to suburbs and what I’ve termed the franchised landscape. But so has the writing of Robert Venturi (Learning from Las Vegas). If I’d relied solely on Kunstler for inspiration I probably wouldn’t have photographed in these spaces. He despises them. Venturi, who embraced what he called the “decorated shed,” (the big box essentially) was inspirational for his open attitude at looking at them from an architectural and functional standpoint. So I’d say this aspect of my photography runs simultaneously parallel with these two writers thoughts - I appreciated Kunstler’s critique of the franchised landscape but also embraced Venturi’s curiosity and architectural analysis of it. That’s why I like to approach all my work as a visual anthropologist - there’s room to both analyze and criticize what I look at.

This aspect of my work is also a continuation of the works done by New Topographic photographers like Robert Adams and Lewis Baltz. I reference them but with a twist: by exploring environmental and economic conditions in inner cities as well I’m asking the questions: what were the causal effects on economics, commerce and housing there (the inner city) as the suburbs were built out?; as manufacturing shifted away from city environments to suburban ones - what impact did these factors have? The New Topographers chief concern was how suburbia was impacting the natural environment, chewing it up. I’m concerned with those factors too, as 2 million acres of farmland get eradicated yearly to development in the United States, but I’m equally (if not more concerned with) the economic and racial factors - the human costs that were the byproduct of suburban build-out in the inner city.

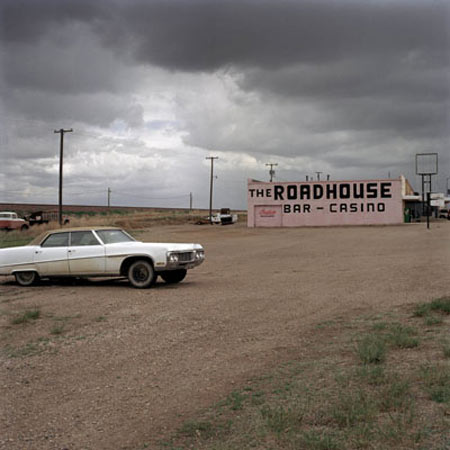

I’ve also been influenced by the writings of J.B. Jackson who celebrated much of what Kunstler decried (Jackson’s work informs The Highway Landscape section of Approaching Nowhere). Jackson came to the car-culture environment in the late 50s - during its flowering heyday - without an agenda, and thought it an engaging venue to explore and write about. He was a cultural geographer, social scientist and astute observer: essentially he said this is what’s before us, let’s look at it. What are its attributes? How does this system work? What does it affect and influence? He was also an anti-beautification proponent: he took the iconoclastic position counter to most social critics of the time who deplored roadside culture. He instead reveled in its boisterous, unplanned nature, which has pretty much been eradicated by big box monoculture and corporate franchises these days. Jackson also understood later in his life that roads were actually a place in and of themselves and acted as vital components in the country’s

transportation infrastructure. He wrote about that too. By taking a polysemic approach to my photography - an acceptance that there are multiple meanings and reasons for and why something exists - it all becomes richer.

I’d like to believe my work (hopefully) blends social criticism with an emotional component: I want to make pictures of not just what is alienating about our built environment, or socially or economically unjust, but I want to make photos that suggest an emotional quality of anomie as well. I guess it’s all open to interpretation and perhaps I’m freighting it too much with my thoughts. But these things go through my head as I shoot. The title of my book is also a slight poke at the growing dis-ease I’ve felt these past 7 years with the Bush Administration in the White House. It feels like the country is approaching a kind of nowhere. We’ve lost our way and the populace still doesn’t seem too concerned about it. So the title functions on some levels similarly to Kunstler’s but then also veers off in the other directions I’ve outlined.

JC: Here’s the one thing that I don’t understand about this all. Having talked to many people I am under the impression that many are aware of this feeling of anomie that you just talked about. Many people really do not like those suburbs and strip malls, and yet more and more people move there. In Pittsburgh, where I currently live, this has the effect that many prefer McMansions in the middle of nowhere over the mid-20th Century houses, built solidly and stylishly, that are so ubiquitous all over the city. How is this possible? I guess I don’t really expect a definitive answer, but I’m sure as someone who has looked into all these different aspects you might have an idea.

JB: The New York Times columnist David Brooks (who I don’t agree with) would tell you the exact opposite: that people actually love living there. His book On Paradise Drive talks about this phenomenon. I personally think it comes down to economics for most Americans. The suburbs are convenient and inexpensive to live in. You don’t have to drive far to get the goods and services we all require, and as the price of gasoline climbs theses factors will become important considerations. For those moving into McMansions out on the suburban periphery, chances are they’re in a higher income bracket and can afford the luxury of having to drive farther to get life essentials. For a while they’ll also enjoy more privacy, but as population continues to expand, what was once a remote area eventually becomes suburbia. Circling back to Kunstler: his latest book The Long Emergency

posits that because of energy costs people will start moving back into city centers to avoid expensive commutes. I think this could happen. People will get tired of the two-hour commute into the city (if that’s where they work). I’ve seen resurgences in places like Cleveland, Buffalo, Asbury Park, New Jersey. There are people out there, usually those marginalized by society, that go where the prices for housing are cheap and then renovate because they also appreciate the aesthetics of older homes, or like the cultural fabric of cities: theater, music, art, good food, the life of the street.

As for the feeling of anomie: it’s a condition of modern life created by many factors, some out of our control, others not - it’s here to stay regardless of where you live or work. Anomie is at the heart of our materialism, acquisitiveness and ambitious desire for “better” and “more.” A Thomas Wolfe quote comes to mind: “there is a terrible and obscure hunger that haunts and hurts Americans, that makes us exiles at home and strangers wherever we go.” So true. We try to fill that hole we experience as human beings with consumer goods and big houses. It doesn’t work. We’ve been a pampered society. That sense of entitlement leads to waste. We’ll have to readjust our thinking about many aspects of our lives and how we live them going forward.

JC: I sometimes get email from people who complain about me linking to political articles in between all the photography. Along similar lines, just the other day I read a review of one of the books, which depicts the destruction in New Orleans and which also contained an essay about Global Warming, with the reviewer complaining about what he felt like a “diatribe”. Have you run into similar criticism of your work?

JB: I really haven’t. The book has only been out 6 months, so maybe down the road my notions will be challenged. For me, simply expressing and reporting on what you’re experiencing and seeing has genuine power. That’s what I tried to do and that’s why I wrote an essay. It’s ok to hint or suggest at political content or intention, but you can’t overdo it, or try to ram it down the viewers throat: I think you want to strive for subtlety. Photographs are open to multiple meanings and you have to allow enough space for that multi-dimensionality to have room to breathe, that’s true. But photographs sometimes need words to unlock their deeper meaning, or words help bolster the artists intent too. I’m ok with that. Many would probably disagree with me on this point - many have the mindset that if a photo needs explanation it’s a failure. When I look at someone else’s work I’m hoping there’s the back story to read about to flush out my viewing experience, enlarge my understanding of that particular artists work and intent.

Regarding your reference to the Katrina “diatribe.” This also depends on one’s orientation. For someone into environmental issues Katrina was perhaps solely about global warming and I’m sure they welcomed seeing that referenced in the book. For someone looking at the racial component like me, Hurricane Katrina - based on recent experiences I’ve had there - was about government negligence, racism and exclusion. Certain Americans were neglected based on their skin color and where they lived. Also to take this down a totally different track - you never know about the packaging or marketing of the book (and I don’t know which one you’re talking about precisely) but perhaps the publisher felt it would reach a broader audience if it had the essay component on global warming. Personally, as artists I think we need to get more political with our work; I see more socially conscious work coming to the fore and I think that’s great. If some of that gets blended into a book to form another layer for viewer contemplation, that’s important and of added intellectual value. There are purists out there, too, that just want their photos without words. I understand that as well. I think there are plenty of rooms at the inn for all types of books, as well as strong opinions expressed in them.

JC: Criticizing artists for talking about the political repercussions of their work seems to be a fairly odd thing to do and, if I may say so, something that I have run across in the US much more often than in Germany. What I find odd about this is that if you show images from New Orleans, say, making the connection to global warming is quite obvious; in a similar fashion, not talking about the causes and implications of sprawl would seem like missing a large part of the actual endeavour of taking photos of suburbs, strip malls, and highways. But of course, you could also just show the images and refuse to make statements about them. Which route do you prefer and why? And what is the artist’s role in society?

JB: First off, I love the political activism of the Europeans. We seem so asleep here by comparison. We could use some wake-up pills.

Someone once said to me that the purpose of art was to educate and enlighten. While I would never suggest that my work succeeds in doing that, it’s something I strive to do for myself - I photograph to learn, to understand, to have an on-the-ground education. Hopefully some viewers might come away from my work thinking about certain things, or making new connections - that deindustrialization in the United States in the late 1970s was actually the onset of globalism; that building freeways in the late 1950s helped destroy the social fabric of inner cities as well as segregating them; that by buying goods at Wal-Mart you’re actually helping to keep workers enslaved making inhuman wages in the provinces of China. I do a lot of reading around the images I take. I also prefer to be upfront about my intentions. As I said in the book’s essay I’m not neutral on the subject of strip malls, the homogenized landscape or segregated, deteriorating inner cities. So I agree with your comments: it’d be considerably less satisfying to just show photographs without commentary.

Artists hopefully will become a more politicized group in this culture as we go forward. I long for a new kind of activism. As an intelligent and informed segment of society we’ll have to step into the breech and keep asking questions about social issues. As a country of 300 million we’re too complacent. Artists need to keep the heat turned up. I personally know several artists/photographers working on water issues or global warming issues, and once you’ve done work with a political tinge it’s hard to revert to being a straight photographer again. My work has moved increasingly into a political arena these past 7 years in a subtle way. Mark Rice in his book entitled Through The Lens Of The City says that “every aesthetic decision a photographer makes is simultaneously a political or social statement.” I agree with this. We should never soften our positions for what I believe are market purposes. Our language can’t be fuzzy; we can’t be afraid to sound too political, or too critical in our viewpoints. We should never take a “will-let-the-viewer-decide-what-my-images-ultimately-mean” posture. This is a cop out and diminishes the power of our work. We have to declare ourselves, even if it makes us vulnerable to criticism. In the essay in my book I do bring language to the photographs. I do criticize. I think language and imagery are inextricably linked. A photograph can only go so far, and depending on the context it’s seen or placed in, can register completely different meanings. You want to make sure the audience gets what you mean: words supplement and support the photography.

JC: There’s this image, which I do not agree with at all, that artists mostly concern themselves with problems and things that matter not all that much to ordinary people. For art with a political intention to really work (in the sense of reaching large numbers of people) something has to be done about this image. But what would that be? Coming back to the photography from New Orleans, one of my concerns about all the photography from there was that while I greatly appreciate all of it, if the venues for that kind of work are art galleries and quite expensive glossy books, the impact might simply be too limited. What can photographers do to expand the group of people who look at work like this?

JB: This question has a few parts so let me take things one step at a time: first off, to address the comment: “…artists mostly concern themselves with problems and things that matter not all that much to ordinary people.” I disagree. I think there are plenty of artists who are dealing with very mainstream societal problems that should be a concern to most people. Look at Al Gore and the filmmakers that made An Inconvenient Truth; Richard Misrach’s Desert Canto series which has been an on-going dialog about man’s destruction of the earth (using the desert as metaphor); Robert Dawson’s important Water in the West project - dealing with perhaps the most important issue facing humanity in the next 30 years - access to fresh water. Hundreds of thousands of people saw the film or the exhibits. I don’t think these are small-time numbers or small-time esoteric problems reserved for contemplation by the elite. The real problem is the culture we live in: most Americans don’t place much value on art or art-making, so how can they be influenced by it? Europeans hold art in higher regard. Therefore the more important consideration is art education: how do you instill in a culture-at-large the notion that art can have a transformative effect on the world and human outcomes?

Secondly, to address the gallery/book question: the audience for photography as seen in coffee table books and art galleries is expanding. Press runs for the books were taking about are in the neighborhood of 5000 to 15,000, and art fairs - that are proliferating around the world - are showcasing work normally reserved for galleries and placing it into a much larger context, which is increasing the “walk-by” audience that can see any given kind of work. This has tremendous benefit if we’re talking about disseminating ideas about global conditions (for instance).

Social change happens because of increased awareness. It’s either from the ground up, where working-class people who once considered themselves powerless, form bonds and unions to get their voices heard. Or you have individuals who have social consciences that might be in a position monetarily or politically to give funds or lend muscle to causes that might foment public policy shifts. The mere fact that art has more venues now enables these things to happen on the high end and low end: more people have more access, and hopefully become more aware and attuned to the work being done by artists with a political bent.

Then look at the internet. There are now artists talking among themselves in a deep and powerful way that was previously impossible. People who are interested see work on-line that would not have been available for viewing ten years ago. The internet is having a tremendous democratizing effect on art and ideas (look at the impact of your website, for instance).

Artists themselves are also subverting or working around the “system” to broaden the reach of their work: they’re trying to develop new paradigms for how work might get seen. I’m thinking here of the Philadelphia artist Zoe Strauss (she was featured in last years Whitney Biennial). She makes color Xerox copies of her work and exhibits the images along freeway underpasses in her neighborhood, or other neighborhoods. The images deal with homelessness, poverty, racism. Ed Burtynsky received an award last years for his environmental work - a cash prize that was donated to a worthy cause that he designated. Because of that media attention he was able to broadcast the environmental message of his work in a very wide way. I think you also have to try and take advantage of opportunities to show work in non-traditional settings - places more people have access to. That would come about by artists perhaps self-funding traveling shows, securing venues, all under their own power. That could happen too, and I bet there are grants out there to support that kind of activity.

JC: Something else that I often think about when viewing photography like yours is the somewhat uneasy relationship between the contents of the photos and their beauty. When you create a photo that is aesthetically very appealing, but that shows something that is not appealing at all, does that create a problem for you? How do you deal with this?

JB: This is a dilemma I use to tussle with mentally but it’s no longer an issue. Walter Benjamin believed that photography was a form of mystification, (which I also take to mean had the ability to “beautify”). Paraphrasing an essay by Susan Linfield called The Treacherous Medium she quotes Benjamin as saying ” it (photography) can endow any soup can with cosmic significance…” (I’m assuming Andy Warhol read that essay!). If someone coming into a gallery situation, or looking at a book, can get into the work because they initially find it “beautiful” or “mystifying” that’s ok with me. That’s a pathway into a deeper conversation. You have to provide entree somehow. The act of photography in a de facto way segregates a segment of reality, reorders it and most of the time renders what’s before the camera as something beautiful. It’s an inherent quality we can’t escape. Even Lewis Baltz’s San Quentin Point is unabashedly beautiful, but obviously that wasn’t his intention. I also think of Pauline Kael’s essay in The New Yorker from the late 80s about Sebastiao Selgado, where she criticized his work for aesthetisizing human suffering. She clearly misunderstood this basic quality of the photograph.

A photographer can (over time) develop an enlarged, almost Zen-like definition about what constitutes beauty; and beauty often transcends and transforms the bleakest of subject matter. Or maybe it’s a question of aesthetics: the subject matter is awful before us, but as formalist animals we fashion something beautiful from something unpleasant - a glimpse of the sublime, perhaps? Ugly, beautiful, mundane: these are just words and constructs ascribed meaning over time. Artists get to subvert, invert and transform those meanings. After all is said and done I think a beautiful photograph of unappealing subject matter still registers as unattractive to the majority of the audience. A slim minority “get it.” I only say this based on people’s reactions to what I’ve done. My sense of what’s beautiful is radically different than most people’s aesthetic. Understanding that helps me move forward.

By

By