A Conversation with Dana Popa

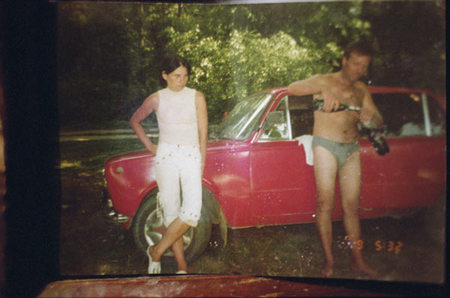

Dana Popa’s “not Natasha” portrays young women for poor Eastern European countries who spent years in other, richer European nations as forced prostitutes. The numbers alone are sobering for a continent that likes to lecture others about human rights (see, for example, this story or this one). But it’s not just a European problem (see, for example, this story). I wanted to talk Dana about what made her work on the project and I wanted to learn more about her experience, so I approached her for an interview. Click on any of the photos to see slightly larger versions.

Jörg Colberg: “Not Natasha” tackles a tough topic - how did you get the idea for it? What motivated you to deal with it?

Dana Popa: I was looking at the Republic of Moldova and I was having the impression of a limbo land. A state of confusion reigns here since this people does not seem to know where it belongs, which past it comes from and which direction to incline towards: The East? The West? I knew it was the poorest country in Europe and that it would be soon right over the new EU fence (in Aug 2006, with Romania joining the EU in Jan 2007). During my research about the country I came across statistics that said 500 sex trafficked women returned home to Moldova in 2005, and I strongly believed I must get deeper into this subject. A couple of years before, while on a train trip, I was reading some sort of trafficking story in a Romanian newspaper. So it was all sort of familiar to me, the same way this issue is familiar to most of the people from the sex slaves exporting countries. I knew the phenomenon was happening, but I did not know much about it. The more I read about it, the more I believed I should try and photograph it. You know, this was my final project for the MA, so surely, I was trying to prove myself I can tell a story in photos, but I very much had this concern in my mind: not many people are familiar with what trafficking really means.

JC: The project sounds like a pretty big thing to handle for an MA - did you never have any doubts whether you could do it?

DP: Oh, when I was photographing it in 2006, I always thought, since I was having the opportunity to do it, I must do everything I can, to do it well. But I always had doubts I could build up a fluent story. I wanted to see more women since the statistics were so high, to listen to more stories, to create more. Working with two NGOs was good since I could put the pieces of the puzzle together and have some material. The doors to one shelter in Chisinau were open, still the access was restricted, me relying on social workers to take me along in their visits to the survivors of sex trafficking. I spent three weeks on the issue, maybe 8 days altogether photographing. I met 17 women who escaped sexual slavery. I was always under the impression that visually, this is an amazing story to tell, but my access was so severely restricted. When I left Chisinau I believed I had some good photos and maybe a good story. After I saw this first part of “not Natasha” edited I knew I wanted to continue the work on it.

JC: The project must have required quite a bit of complicated planning, to get doors opened and to get access to the women, to gain their trust… How did you go about this? How did you decide how to deal with the topic photographically? Did you have ideas beforehand, or did you let things develop?

DP: Nothing was arranged by the time I left for Moldova to try and document it. I only had the contact of the Director of Amnesty International Moldova; he gave me two other contacts, and I started from there. I worked with two NGO’s : IOM Moldova (International Organization for Migration) and Winrock International. I tried to work with another NGO - simply because it was very difficult in convincing the social workers to take me to the women who had been trafficked, so I always had the impression I don’t have enough material, but with this 3rd one, it didn’t work. In Romania, too, I could not document it. The police laughed at me. They laughed saying something like: ‘you are dreaming if you want to expose such a subject now, when we are on the brink of joining EU?’.

These two NGOs gave me access to the women who returned to Moldova after escaping traffickers. I spent two weeks at the IOM Moldova shelter just talking to the girls and sharing walks with them, a getting-to-know-each-other process. These girls had just escaped sexual slavery abroad. I really did not want to photograph the story here, at the shelter. I had a concept and I was following it: to photograph the survivors of sexual slavery in their familiar places - as in comprehending more of where they left from, why they wanted to leave, where they returned to and how they managed to live under this terrible secret that shadows them. Imagine, by the end of the second week I had only visited one woman and one house where two sisters that got trafficked together to Turkey had been brought up. The waiting was frustrating, but beneficial for the story, I understood later; I used this time to become friends with the girls and to listen to their personal stories- that gave me a close, in-depth and in-detail look on the phenomenon. What they went through while sex trafficked, horrific details they would share with me and amongst themselves, contributed to shaping up my vision on how I would photograph. To keep a narrative flow was always on my mind. This seemed to me a bit difficult at the time since I was dealing with the same past story: a woman who had been tricked into traveling abroad with the offer of a great job, held captive, sexually enslaved, then she escaped and lived, now back into her home with a fractured soul, humiliated and violated, but hey, so strong were some of them and so weak others. I did use my little time to explain who I was and why I wanted to listen to their story and to photograph them. I tried to be discreet and to cast a gentle look on their suffering.

So to resume, I had to let myself carried by what was offered to me, still keeping the initial concept. One thing I could not do that summer: photograph the missing women, to which I returned the next year, in 2007. Then, the getting access process became even harder since the NGOs did not help me much and I had to find on my own the addresses of households that declared their daughters, wives, mothers missing under the circumstances of what trafficking means.

JC: When you look at the reactions to this project, do you feel you achieved what you wanted to do? Do you maybe think there should be more exposure?

DP: Well, the feed back I always had on the project was fantastic. There were a couple of important moments when I learned about my project out of people’s reactions and comments on “not Natasha”. I don’t know how to say it without insinuating that this story is more important than other human rights topics. It’s not only about the sex trafficked girls, it contains them within it. People talk to me about the project, about the feelings “not Natasha” induces for them. And it’s what I hoped to achieve through my photography on the subject.

When Mark Sealy at Autograph ABP decided to commission me to develop the work I knew I had the chance to continue the project ,and for me this was so important! The work, limited only to survivors’ first chapter received a great feedback; but it was incomplete for me, so I took the chance to photograph in a more metaphorical approach. I looked at the spaces the missing women have lived in their whole lives, their presence still felt and the longing for them so deep and old; in correlation, I toyed with the idea of the space where some of the sex trafficked women ended: the work rooms. And here I was captivated by the interior details of a caged life. Autograph ABP decided that the work needed to be put together in a book, which I entitled “not Natasha” - I needed the voice of the girls who came out of sexual slavery to be heard. And they had told me how much they hated the name of ‘Natasha’, which is a nickname clients and pimps use for prostitutes. That is where I am drawing the distinctive line between willing prostitution and sexual slavery. The discreet size of the book is meant to remind of the passport which plays the initial role of key to a better life and in the end it becomes the key to lock the door of sexual slavery. Or to remind of the girls’ diaries. “not Natasha” is their journey. The layout is simple: a collection of photographs that hopefully talk for themselves, the wording discreet. The captions are not many, just a few, but most of the times I used the girls’ own words. They were strong and honest words and shocking for me.

I think the project had a good exposure. Now, with the book being published and the events organized around it, I am hoping the exposure to be even larger(there is a “not Natasha” exhibit at Photofusion London).

JC: Thinking back and knowing what you know now what would you have done differently - if there is anything you would have done differently?

DP: I don’t know. Yes, I would have done something else different regarding one trip. I wanted to follow a girl in her journey from the country where she was trafficked to her home. It was not essential for the story, but I had this in my mind for a long time and I tried to make contacts with NGOs in Italy and Spain that would send identified sex trafficked women back to Moldova or Romania. I ended up by going to Turkey - this is a huge destination for traffickers and huge market for sexual slavery, my trip was not as successful as I wished; I only managed to do the trip more than 400 deported sex trafficked women had done on a weekly boat from Istanbul to Odessa. So here, I think I would have made better contacts before jumping into the trip. And I wouldn’t have had tea with Kurdish pimps trying desperately to get into the underground world of prostitution and trafficking in Turkey - nothing happened, but I was told next time to think twice.

JC: And, of course, what’s next?

DP: Well, next… I usually avoid talking about a next project if I have not passed the middle of the making of it. I started a project on the ‘untouched by communism’ Romanian youth, an attempt to look at the country through the perspective of these teenagers born at the very beginning of the ‘freedom’ or post communism age, if you want. I hope I can develop it.

By

By