A Conversation with Curtis Mann

If further proof was needed that it’s not the tools that produce art, but the vision of the artist, Curtis Mann’s work would provide a good example. I had long wanted to talk to him about his work, and I finally got the chance to do so.

Jörg Colberg: In the day and age of easy image manipulation with Photoshop you modify your photos by attacking actual prints with bleach and other tools. Why is that? Wouldn’t it be easier to do it all on the computer? How did you develop this style of work?

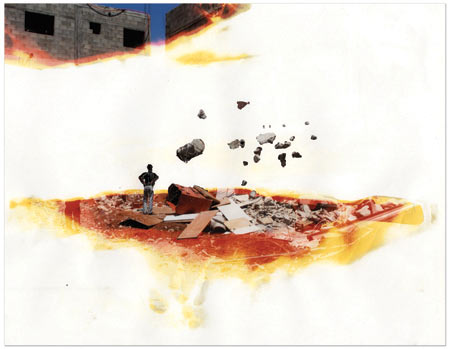

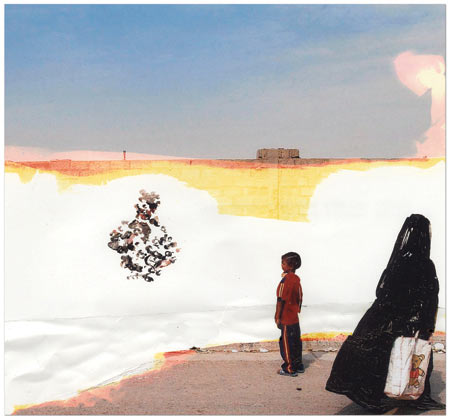

Curtis Mann: I have always been curious about the physical nature of the photograph (at least when it is printed). Paying attention to the photograph as an object exposes it as something impermanent, fallible and extremely malleable. Coming from a mechanical engineering background, I have always been curious about the paper, the chemicals and the inks used to produce photographic images. They are the birth of the image and their manipulation holds a lot of potential for disrupting the powers of the flat, conventional, image.

It might be easier to create the aesthetic of my images digitally but I feel that the physical processes I use has a strong metaphoric meaning and conceptual connection to the ideas I am interested in. Terms like erosion, destruction, erasure or imperfection are always bouncing around in my head while making my work or scouring images that represent pretty complex places. I hope for my manipulations to facilitate a new way of engaging these ideas on a more obtuse, less obvious manner.

Photographs have the amazing ability of making the viewer forget or ignore the fact that they are looking at a thing, an object.

Of course, a whole new dialogue begins when we start completely viewing images via screens and computers. This is an interesting new arena to think about and consider how this system can be disrupted or rethought in a continued pursuit of breaking down our processes of looking at and understanding images.

JC: Working on individual images the way you do it creates the absolute opposite of what one would get with Photoshop: Something that is unique and that cannot be easily reproduced in large numbers. Is this something you had in mind when you developed what you’re doing?

CM: I didn’t really consider this quality when I first began the work and try not to use the unique object as crutch in value or consideration. I am able to make multiple versions (albeit not perfect reproductions) of one piece but would definitely have a hard time with making editions as large as a traditional photographer.

I have grown a fondness to the idea of making multiple, unique versions of a piece. There is something about that simple quality of uniqueness that I feel we just don’t aspire too enough. The mechanical reproduction of seemingly endless amounts of perfect photographs starts to encourage us to consume them faster, trying to keep up; but at that we start to cut down on time spent really challenging what we are looking at, thinking about it and then rethinking it.

All of the little scrapes, scratches, crumples, peeled areas in my work function as a way to keep a viewer around just a little bit longer, engaged long enough that maybe a different part of their brain might start reconsidering initial ideas or understandings. I hope that emphasizing the unique qualities of individual pieces in my work can encourage someone looking at the front page picture of a newspaper to slow down, look at that image and move around it both physically and mentally.

JC: I’m wondering whether you mode of work will put you at odds with the modus operandi of fine-art photography galleries, which rely on editions and which lately have pushed prints to bigger and bigger sizes (for obvious reasons). Is that something you are concerned about, especially given that you’re at the beginning of your career?

CM: I definitely have been worrying about these issues much more than while I was in the bubble of graduate school. During a couple of studio visits, I have had gallery owners who were immediately turned off by the size of some of my works. On average my pieces range from 11x14 up to 20x24” which is much smaller than most paintings/photographs today. The reality of the situation is that my smaller pieces sell for less than my larger pieces, even though I see them as equals. When your income depends on art sales, this is a hard thing to come to terms with.

I have made some larger grids (made up of smaller pieces) which allows me to have a size that can anchor a certain space or certain aspect of a show while keeping a small, intimate aspect to the individual pieces. In the end, I just feel my work starts to fall apart at larger sizes and conceptually starts to get a little to far away from their vernacular beginnings. I am lucky to be currently working with a gallery where I have never been pressured to work outside of my artistic decisions. It is comforting to see successful artists working small too. I have always been enamored with and influenced by the work of Richard Tuttle and try to use him as an example of not fearing the small piece.

As far as editions go, I have compromised a little. As mentioned above, I create small editions of most pieces, but each piece is slightly different than the other since each one is handmade. I keep these editions pretty small mainly because of the workload it would take to produce so many pieces. This is not so much of a concern, especially with many photographers today already working in such small editions, that its not so different. In the end, I just couldn’t bare to make only one piece, and never be able to sell or share that piece with anyone else again. I don’t know how painters deal with that.

JC: The lack of Photoshop as a tool only superficially makes your work different from digitally manipulated work, in the sense that in both cases the final image is being created from a source photograph (which most people, especially in the United States, would think of as something “real”), with orthodox restrictions of what a photograph is and means being discarded (in your case bleached away). So one could easily argue that you are engaging in expanding the boundaries of photography in a very similar fashion as people who digitally modify photographs. Is that a description you’d be comfortable with?

CM: Definitely. I think my work is heavily influenced by the possibilities of digital manipulations and the many artists working with those tools. Fundamentally, digital has played an immense role in encouraging a healthy skepticism and disbelief in the image to a much larger amount of people than ever before. Once that truth is disrupted people are responsible for their own truths, or how much they want extract from an image. I am very much interested in following in these footsteps.

Formally, as someone who found photography while it was already in a digital era, I have always been enamored with the nearly infinite manipulative possibilities that the computer offers. So many artists are trying so many different things that I am always encouraged to be as curious, and challenging as possible when dissecting the photograph and its conventions.

I think digital has played a major role in actually encouraging a much more contemporary, conceptual and idea based approach at using physical, dare I say, alternative processes. Digital proved that no matter what tool you are using and how cool it looks, if that process is not part of the meaning and understanding of your work then it just becomes another Photoshop filter or an exercise in aesthetics.

JC: Into what direction do you see photography evolve?

CM: Photography itself seems to grow smarter, more sophisticated, more intelligent at a pretty constant rate. I’m just hoping that we keep up with it, that we stay educated and keep exposing its tricks to the rest of the world. Photographs are fascinating to me because they are amazingly ubiquitous, and usually benign, but also have the potential to be extremely subversive, even dangerous.

JC: Why (or how) dangerous?

CM: Images that are smarter than those looking at them have a scary ability to cause influence, either for bad or good. As, the number of images we encounter each day continues to grow, the time spent with each one diminishes and with that, the time questioning, analyzing and coming to our own conclusions starts to disappear. The lessening of the individual thought process and a decrease in critical curiosity allows for more apathy, less empathy and I think a generally misguided understanding of what is actually happening around us.

JC: And then I also want to ask into what direction do you see your own work evolve? Have you spent time thinking on what kind of work you might do in five or ten years, or is this something you’re not too concerned about?

CM: I am constantly thinking about what is next and am always experimenting with new subjects, materials, new places and new ways of working. I have been dialoguing with a good friend who works a great deal in the Balkans and I am again intrigued by their complex histories, current wonders and contemporary political struggles.

With my current work, a certain amount of the process is tied to the struggle of connecting with these images of places I have never been, through photos by people I have never met. I am interested in changing this aspect of my working process. I am curious about how physically traveling to some new and different places, meeting actual people, touching the actual ground will affect my working process and conceptual thinking both about photography and the places themselves.

As for ten years from now, all I can do is keep allowing my curiosity and mischievous nature continue to guide my work and see where it takes me. I also hope I have couple of kids too.

all images are clear acrylic varnish and graphite on bleached c-print

By

By