A Conversation with CPC 2009 Winner Bradley Peters

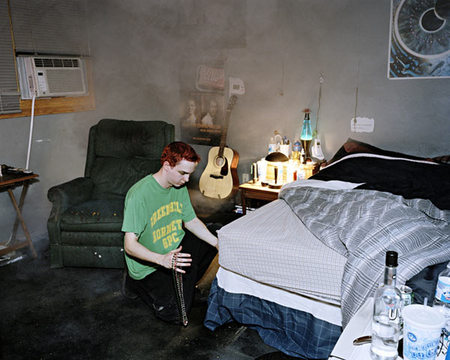

Bradley Peters is one of the winners of this year’s Conscientious Portfolio Competition. A recent graduate from Yale, his work marries what might be thought of as the currently dominant Yale aesthetic (which often involves staging photography) with the flash-heavy, completely spontaneous kind of photography that has been very popular in Britain. Ultimately, such a simplifying description really doesn’t do anyone a big favour, but it might serve well to come up with a first, crude description of the work - and knowing what I know now after having done the conversation with Bradley it’s not even that far off!

But of course, ultimately the photographer’s vision is more important than what his work might look like - or how it can be placed into the photographic canon (I leave that to the academics). What I found particularly striking about his work is not only its quality, it’s also how effortless its execution appears. Even what might look like little mistakes or inconsistencies upon closer inspection reveal themselves to be part of a grander scheme - while remaining actual little mistakes or inconsistencies.

For me, as someone who has been looking at a lot of photography over the years, this points to a photographer who is very comfortable with his work, who clearly knows what he is doing, and who is willing and happy to find his own, unique photographic voice while remaining true to his roots. Quite the accomplishment! Bradley clearly is one of the most promising young talents to have recently emerged from Yale.

The following conversation with Bradley was conducted via email (as are all the conversations actually). Click on any of the images (which, of course, are copyright Bradley Peters) to see slightly larger versions.

Jörg Colberg: In your “Home Theater” statement, you’re describing your work as “allowing a ‘staged’ photograph to break down and […] then [to] spiral into the spontaneous.” I just have to ask - especially given your Yale background: What’s wrong with staged photography? Why have it break down?

Jörg Colberg: In your “Home Theater” statement, you’re describing your work as “allowing a ‘staged’ photograph to break down and […] then [to] spiral into the spontaneous.” I just have to ask - especially given your Yale background: What’s wrong with staged photography? Why have it break down?

Bradley Peters: It’s not an issue of something being “wrong” but rather my interest in something that no one seems to speak of much these days… luck. I’m not interested in coming up with a really well defined idea and then making a picture that illustrates that concept. My photographic foundation was built in small camera, black & white street photography, I mean that’s basically the only way I shot for nearly ten years, and I’m still really interested in letting the world reveal itself in ways that I can’t imagine by myself. Without the breakdown there is very little surprise, which is important to me. I need to feel as though I learned something from the image and if the picture turns out exactly the way I wanted, I probably didn’t learn anything that I didn’t already know. In a way, I probably didn’t even need to make the picture in the first place. There was a really good interview in LA Weekly a couple years ago with John Szarkowski that I think speaks to this point:

“Some photographers think the idea is enough. I told a good story in my Getty talk, a beautiful story, to the point: Ducasse says to his friend Mallarmé — I think this is a true story — he says, ‘You know, I’ve got a lot of good ideas for poems, but the poems are never very good.” Mallarmé says, “Of course, you don’t make poems out of ideas, you make poems out of words.’ Really good, huh? Really true. So, photographers who aren’t so good think that you make photographs out of ideas. And they generally get only about halfway to the photograph and think that they’re done.”

The idea for me now functions as a starting point or a launching pad for potential rather than the thing that is trying to be expressed. Something new happens where the residue of the original idea still exists but the image has taken on a life of it’s own. I’m a huge sports fan and I noticed the day after watching a game, the conversation that I have with other sports fans is dominated with us discussing all the amazing plays we witnessed. Then, it occurred to me that these plays almost always have a component of near failure involved in them. It’s the fingertip catch, the unlucky or lucky bounce, or a player making a grab on a line drive that shouldn’t have been catchable. It’s almost never the “perfectly executed play” or the “high percentage shot” that makes us leap up from our chairs in disbelief. I feel the same way about photography.

JC: But isn’t that the essence of photography - or of any art form - that chance will always intervene and that your ideas almost never come out the way you think they come out? I mean I’ve heard your argument from various people, usually when people voice their unhappiness with conceptual or staged photography: The fact that it’s conceptual or staged doesn’t mean that you can really plan each and every detail. Trying to be an artist without having an openness to anything you can’t control is like pretending you’re one of those Japanese robots who can “play” the piano, isn’t it? You might end up playing the piano, but you’ll sound like a robot. What I’m after is that it’s almost like people think you can either plan everything, or everything is left up to chance, whereas in fact reality tends to usually lie in the middle, doesn’t it?

JC: But isn’t that the essence of photography - or of any art form - that chance will always intervene and that your ideas almost never come out the way you think they come out? I mean I’ve heard your argument from various people, usually when people voice their unhappiness with conceptual or staged photography: The fact that it’s conceptual or staged doesn’t mean that you can really plan each and every detail. Trying to be an artist without having an openness to anything you can’t control is like pretending you’re one of those Japanese robots who can “play” the piano, isn’t it? You might end up playing the piano, but you’ll sound like a robot. What I’m after is that it’s almost like people think you can either plan everything, or everything is left up to chance, whereas in fact reality tends to usually lie in the middle, doesn’t it?

BP: There really doesn’t seem to be much that actually happens on the bookends of many spectra! I don’t know if you play cards much but it’s the difference between a player who plays “tight” or one that plays “loose”, both can be successful, both are valid ways of playing, it’s just how the player has decided to approach the game. You can’t eliminate chance from cards but there are different ways of dealing with it. I think it’s the same for artists. Not too long ago I was listening to the Jeff Wall talk on the Tate Modern website, about his performers giving him “gifts” when they do something that he had not planned for. The difference for me is I just happen to be interested in these “gifts” to the point where I care very little about the original idea anymore. For example, the image with the boys throwing the light bulb happened at the very end of the shoot. We were working near the bushes directly behind where the boy with the hooded sweatshirt is standing. After we were finished their mother instructed them to help me pick up my stuff. The boy in the hooded sweatshirt grabbed the light bulb and tossed it to his brother. It was completely amazing! I did not plan on this being the picture… it just sort of happened by chance, but it would’ve never happened, I mean I wouldn’t have even been there, if I hadn’t attempted to stage a different image. It’s a spontaneity that was created by the existence of the staged event.

A really important moment for me as an artist actually took place on an outdoor set of a Gregory Crewdson shoot (whose work I have great respect for). I was standing there watching all of the work that goes into making a single image….. everything was very exact, to the point where people were moving parked cars a couple inches to make sure they were right were he wanted them. It was close to dusk and I ended up becoming mesmerized by a long string of tinsel that was strung from the top of the building to a large stand-alone sign that was about 45 feet away. The light on this tinsel looked spectacular, I mean it was beautiful! So anyway, the shoot is about ready to start, the people are in place, and I’m just standing there staring at this dumb piece of tinsel. Then, I notice two guys who are in one of those mobile lifts start to make their way over to the sign. Once they get there, they raise the lift and cut down the tinsel. I was really confused as to why they were taking out the one thing that I had been staring at for the last couple of minutes. I was trying to figure out what was going on, and I come to find out there was a slight breeze that was keeping the tinsel from remaining perfectly still. It couldn’t be in the photograph because it was moving. I couldn’t believe it.

JC: I know this is almost a bit unfair, given that that’s not really what you’re after, but can you tell me what the original idea was that ended up being that particular photo? And what did you tell the “models” about the idea and what to do?

JC: I know this is almost a bit unfair, given that that’s not really what you’re after, but can you tell me what the original idea was that ended up being that particular photo? And what did you tell the “models” about the idea and what to do?

BP: I had been thinking about children who grew up in the era around the time photography was invented, and how in contemporary movies about this time period, there always seems to be one cut away shot to a group of children as pickpockets victimizing the elderly. I find the idea of children as trained thieves interesting. So the idea for the image was for the kids to be passing various items out of a window in a small-scale burglary. There were three kids in this image but the third isn’t included in the final image with the light bulb as he was still in the house. I don’t recall any specific directions that I gave but it was probably something like — start passing things to your brother and then once he puts it on the ground, pass him something else - To be honest I don’t know if it was even that specific. I try to give as little information as possible.

JC: You’re also writing that your “generation might be the last to have believed in any form of photographic truth”, which has you “aspiring for a better, stranger kind of fiction”. I remember reading this at various occasions and always thinking that by allowing the staging to break down and chance to enter, you’re actually getting back to the idea of some kind of photographic truth - where truth enters simply because as a photographer you’re giving up control, and the camera gets back to recording what is happening. I’m sure that’s not how you mean this, maybe you can explain this a little.

BP: I believe if people are predisposed to believe that something is “untrue”, when you present them with something that is “true” but looks like it shouldn’t be, the image is charged in a way that amplifies both the photographic truth and fiction. Letting go of control and allowing life back into my images is very important to me but I want it to co-exist with the photographic fiction that is also inherent in photography. It’s this tension between spontaneity and theatricality that makes it interesting. I try my best to get out of the way a little bit and let the camera show me something.

JC: I’d be curious to learn a little bit how you arrived at your own aesthetic?

JC: I’d be curious to learn a little bit how you arrived at your own aesthetic?

BP: Like just about everything else I do, I pretty much just stumbled into it. I made a rule for myself a long time ago that my camera equipment could never reach the point where it prevented me from being able to go on a long walk due to its size or quantity. So in situations where a lot of photographers would use fancy lights, I use flash. Prior to Yale I never really tried to ‘stage’ an image but I thought I should give it a try since I was in grad school. I ended up making some really predictable and boring pictures of what I thought were good ideas, ones that sounded good when I spoke about them but the pictures themselves didn’t have any sense of urgency. I was really frustrated. Then one night during the summer between my first and second year, I was up late watching a re-run of Seinfeld where Jerry says to George “if every instinct you have is wrong, then the opposite would have to be right”. The next morning I decided that all of my ideas for photographs had to start off as a bad idea; instead of trying to come up with good ideas and translate them into a photograph, I was going to start with something really dumb and obvious but abandon the idea once I started to shoot. I would offer very little direction and just sort of let things develop on their own. In a way I ended up just standing there waiting for a moment of wonder.

JC: So your photographs are truly all singles - there are no contact sheets with variants of images? There is no way for you to go back and re-shoot something?

BP: I take a lot of frames while shooting and I guess you could say that I end up with many variations of that event but the images that stand out to me are the ones that feel completely different from the rest. I want to be clear that “staging” something is a very important part of my process, but the staged event by itself isn’t what I’m searching for, it isn’t enough for me. My work sort of hangs out in a funny space in that way. I’ve tried to go back and re-shoot images but 99.9% of the time I come back with a different image or a watered down version of what I got the first time. Part of what makes it interesting, is the people I photograph end up doing amazing things that they don’t even realize are amazing. When I try to re-shoot something the people have already been through the process and have a different level of awareness that I think inhibits them. In the images that work for me there is a tension between the person who is trying to perform my bad idea and the person allowing something very specific of herself/himself to show it’s face, if only for a fraction of a second.

JC: And which photographers would you name having had a big influence on you?

JC: And which photographers would you name having had a big influence on you?

BP: For photographers work I would have to say Eggleston, Winogrand, Arbus, and WeeGee probably had the biggest influence on me. Tod Papageorge, John Pilson, Gregory Crewdson, Tim Davis, and all of my classmates probably had the most influence on me as people. I owe them all big time.

JC: Are there non-photographic artists whose work has inspired you?

BP: Yes. Olafur Eliasson, Peter Fischli and David Weiss, Eric Fischl, Alfred Hitchcock, Steve Martin, Aphex Twin.

By

By