A Conversation with Christopher Anderson

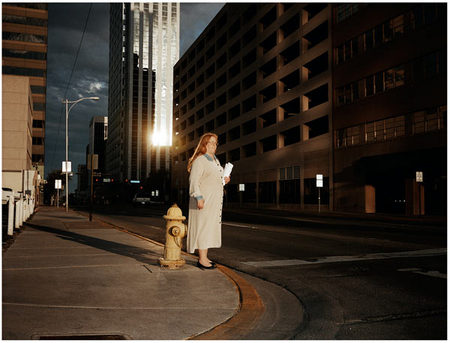

After publishing my review of Christopher Anderson’s Capitolio, I ended up exchanging emails with him about the work and its purpose and reception. Things got so interesting that I thought this would be a great opportunity to take things public and to have a conversation with him on this blog. Thankfully, Chris agreed. Note that larger versions of all images (all of them, of course, are copyright Christopher Anderson) can be seen by clicking on them. The b/w images are from the book, and they are presented just like in the book (see the conversation for details).

Jörg Colberg: Your new book, Capitolio, deals with Caracas, the capitol of Venezuela. Venezuela of course is ruled by Hugo Chavez, who, depending on what view you subscribe to, is either hailed as the most important saviour of impoverished Latin American masses (just short of Jesus) or as one of the worst dictators in the whole world (just short of Hitler). So you got yourself injected into a very toxic situation - why did you go for that? Why Caracas?

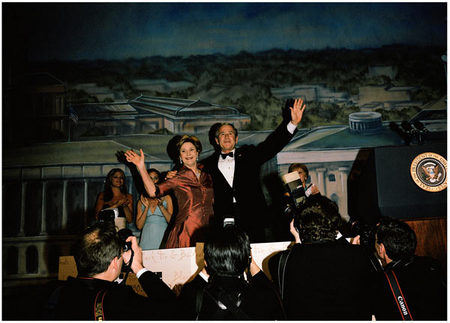

Christopher Anderson: When I started the work there, I wasn’t looking to make a political statement about Chavez. I still don’t believe I am making a statement about the internal politics of Venezuela at all. I did set out to to make a portrait about a time and a place that I, through a series of circumstances, got caught up in. If there were statements to be made, they were universal themes about a part of the world where crushing poverty, fabulous wealth, violence, sensuality, fear, anger, propaganda, etc. are part of the cycle of life. Capitolio is a metaphor and could be any one of many different Latin American cities at any one of many different time periods throughout history. Of course when making a portrait of this place, the politics could not be avoided and Chavez was inevitably going to play a role in the book. But my intention is not to make judgements against or for him. He is just one among many parts of the landscape. Chavez, in this book, is not the illness or the cure, he is merely a symptom. He is at the end of the book to suggest that, if anything, all the ills we see before provide a context for the rise of a figure like him, and that his presence must be understood against a backdrop of what this place is like… not that Chavez creates all of these bad things.

Of course I expected polarized political debate, but it was my curiosity that led me to this set of pictures, not an agenda.

JC: The problem I see, though, is that with Chavez being such a polarizing figure, what you were after might just get lost in the kinds of debates, which seem to have become almost the norm in this early 21st Century: People shouting at each other, completely ignoring the actual topic. Given you anticipated this beforehand, how were/are you going to deal with this?

JC: The problem I see, though, is that with Chavez being such a polarizing figure, what you were after might just get lost in the kinds of debates, which seem to have become almost the norm in this early 21st Century: People shouting at each other, completely ignoring the actual topic. Given you anticipated this beforehand, how were/are you going to deal with this?

CA: As my father always said, “Dogs only bark at the cars that move.” No matter what you do there will be people who will hate it, maybe even kick and scream about it. That won’t change, so I don’t plan on doing anything to deal with this. The work is not changed by the debates, and there will be people who do get it, and at least I will get it. Interestingly enough, I find that Latin Americans themselves get the book easier than non Latin Americans. My survey is unscientific, but that is the impression I have.

Anyway, these debates usually take place in a political realm (the NYTimes Lens blog for example), and they really have less to do with me and my work than the abstracted emotions of the issue (just like the screaming at Town Hall Health Care debates are not at all about the issues but about generalized angst). So I admit that I was surprised to see how the political emotion played a role in the discussion on 5B4.

JC: Capitolio doesn’t contain any text - apart from some text in some of the images, so you can basically read anything you want into the book, in particular your book can be seen both as criticism of Chavez (who appears in various of the photos) or as support of him. Why did you refrain from providing (con)text?

JC: Capitolio doesn’t contain any text - apart from some text in some of the images, so you can basically read anything you want into the book, in particular your book can be seen both as criticism of Chavez (who appears in various of the photos) or as support of him. Why did you refrain from providing (con)text?

CA: I like the play on words of “(con)text”. May I use that?

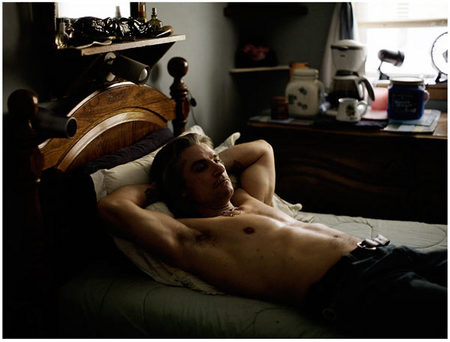

There were two reasons for doing this. First of all, I wanted to test an idea I have been obsessed with: ripping cinema from the screen and stuffing it onto the printed page. This book has a few influences and references that are quite obvious. But I hoped to take those references in a new direction by making a film in book form (perhaps this has already been done in a photo book, but I am unaware of it if it does exist). So, I chose to shoot in black and white as to not interrupt the cinematic experience with color, I break the confines of the page format by having some pictures begin on one page and continue on the next, and I chose not to have any type-set text so that there would always be forward movement to the next frame. The text that appears has been stenciled and then photographed so that it feels more like credits in a movie and the film reel remains unbroken.

Secondly, the book is intentionally ambiguous. I play with the language of “revolution”. The cover is red, the title is stenciled, even the way I photographed for this particular work plays on the idea of iconic propaganda photography of other eras. The section that deals with the industry in particular makes us think of perhaps Soviet era worker propaganda. On the surface, these things suggest a gloriousness, but obviously the book is dark and we sense a rotting from within, a decadence. Is it criticism? Glorification? I’d like to think it is both at the same time. Nothing is all bad or all good.

Perhaps it is an expression that I want to be a believer, but I am always skeptical of true believers. And somewhere in there I think you will find what the book is really about: my own desire to give myself over to the cause… to be taken over by an ideal… but my skepticism and cynicism get in the way. Including text could make this book a polemic. The one thing I didn’t want is for this book to become didactic in that way.

JC: Is that something you’d see as maybe desirable? Less didactics, more art? Incidentally, I just read an interview with a German singer and author, who told a German magazine that didactic art, for the most part, often just becomes embarrassing, and it fails to achieve its supposed purposes. Mind you, this is not a statement that things should become apolitical, but maybe that things can be political in ways other than telling people explicitly what you’re after?

JC: Is that something you’d see as maybe desirable? Less didactics, more art? Incidentally, I just read an interview with a German singer and author, who told a German magazine that didactic art, for the most part, often just becomes embarrassing, and it fails to achieve its supposed purposes. Mind you, this is not a statement that things should become apolitical, but maybe that things can be political in ways other than telling people explicitly what you’re after?

CA: I don’t know about less or more desirable, and I would certainly never argue with a German singer. But for this particular body of work, in this particular form, dealing with this particular subject, in this particular way, anything didactic would destroy what I had in mind. It would change this book that is an attempt at sort of de-mystifying the single, photographic image by making a photo book that is not about the photography and turn it into something preach-y and wanky. I didn’t want a “let-me-explain-something-to-you-and-show-you-how-pretty-my-pictures-are” book. Perhaps I was swinging for the fences, but I really did want to do something with a book that I had not seen before.

JC: Given there is no text, Capitolio also seems like a very clear deviation from standard photojournalism, which has recently come under attack, both from a business point of view (who will pay for it if newspapers are cutting costs when they’re not dying?) and from a photography point of view (are photojournalists covering too narrow a field?). I know this is a big question (and there probably is no need to talk about the business side, since it might well be outside of what individual photojournalists can influence), but where do you see photojournalism go? Will it change? And, of course, how do you see yourself working in the field in the future?

CA: Capitolio, in its book form, as you astutely observed, is not photojournalism, at least not in the way that that word is loaded. True, some of the pictures were taken and originally used in a journalistic context, but assembled as they are in the form of the book, the term photojournalism is inaccurate. But I have always felt uncomfortable with the term “photojournalist”. In terms of my documentary work, there has always been a difference between my role and that of a reporter. If there can be a comparison, it is that I am perhaps an editorialist. My job has always been to comment on what I witness as opposed to the reporting of an event. I am subjective. I have a point of view. There is no such thing as objectivity in photography. I don’t believe in facts, but I AM obsessed with truth. And my work always deals with this distinction (my first book, Nonfiction, is an example). My work is a truth, but it is my truth, my experience. That is all I can offer.

In terms of what that means for Photojournalism (capital P), that is a large question. I don’t think this idea of subjectivity is anything new, it is just that somewhere along the way, we convinced ourselves that the glorious photojournalism was about objective fact. In reality it never was. Robert Capa himself photographed in the Spanish Civil War as an act of anti-fascist combat, not as an objective reporter. Perhaps a more precise question is what it means to photography with a small p. What I mean to say is that I believe this line between what we call photojournalism and fine art photography no longer exists (let’s exclude from this conversation wire service news photography and purely esoteric conceptual, fine art photography). I am very much a part of a generation of photographers that wanted to explode this distinction between art and photojournalism. We don’t even have this conversation anymore, because it is no longer a valid starting point.

In terms of what that means for Photojournalism (capital P), that is a large question. I don’t think this idea of subjectivity is anything new, it is just that somewhere along the way, we convinced ourselves that the glorious photojournalism was about objective fact. In reality it never was. Robert Capa himself photographed in the Spanish Civil War as an act of anti-fascist combat, not as an objective reporter. Perhaps a more precise question is what it means to photography with a small p. What I mean to say is that I believe this line between what we call photojournalism and fine art photography no longer exists (let’s exclude from this conversation wire service news photography and purely esoteric conceptual, fine art photography). I am very much a part of a generation of photographers that wanted to explode this distinction between art and photojournalism. We don’t even have this conversation anymore, because it is no longer a valid starting point.

Much is made about the idea that Magnum now has “fine art” photographers. But what an Alec Soth or a Jim Goldberg does is in fact documentary photography. Their approach and tools may be slightly different, but fundamentally it is documentary photography. What then is the distinction? Is it the large format camera? Is it the subject matter? Is it the black and white film? By what criteria would you place a Nan Goldin on one side of the line or the other? Or a Luc Delahaye, or William Eggleston or even a Andreas Gursky? What about Robert Frank? In this sense I feel freer than ever before. I feel totally liberated from terms like “photojournalist” or “fine art photographer”.

JC: For the most part I’d totally agree with you; but there seems to be one problem: If I was a newspaper or magazine editor and I needed a “story” about some topic, I’d think of getting a photojournalist, someone who is used to traveling somewhere, taking pictures sort of quickly and then coming back with something - instead of a “fine-art” photographer who’ll do the same, but without much of an eye for deadlines or images etc. I’m simplifying things a bit, of course - but given that somebody usually/often has to pay the bill for this kind of work, it would seem that the distinction - which we’d both love to get rid off anyway - might just live on for a while?

CA: You didn’t get the memo? There aren’t newspapers or magazines assigning stories any more:) I think there are some editorial photographers whose hearts just leapt at the hope of that thought. Seriously though, I think what you are talking about is a certain set of skills that a particular photographer might have (working quickly, meeting deadlines, finding their way into the right situation without their hand held, etc). But I don’t think that is the definition of photojournalist or “not-artist”. Andres Serrano has photographed “stories” for magazines. Likewise Gursky, Eggleston, I could go on. But you are right, if I were an editor, I probably would not hire Sugimoto to photograph a story in Afghanistan, but then again I probably wouldn’t hire Bruce Gilden to photograph large format, color landscapes of the Grand Canyon… not that you wouldn’t do a great job, Bruce :)

JC: Sounds like you’re really not all that concerned about the future of photojournalism (both as far as the business and the craft are concerned), which I find rather refreshing given all the brouhaha that is currently produced about the end of newspapers and the struggles of photojournalists. Is this correct? Or are you panicking inside, while remaining cool on the outside?

JC: Sounds like you’re really not all that concerned about the future of photojournalism (both as far as the business and the craft are concerned), which I find rather refreshing given all the brouhaha that is currently produced about the end of newspapers and the struggles of photojournalists. Is this correct? Or are you panicking inside, while remaining cool on the outside?

AC: Not cool, just that I have already shed my tears. The death of journalism is bad for society, but we’ll be better off with less photojournalism. I won’t miss the self-important, self-congratulatory, hypocritical part of photojournalism at all. The industry has been a fraud for some time. We created an industry where photography is like big-game hunting. We created an industry of contests that reinforce a hyper-dramatic view of the world. Hyperbole is what makes the double spread (sells) and is also the picture that wins the contest. We end up with cartoons and concerned photographer myths (disclaimer: yes, there are photographers doing meaningful work)

Of course I am worried about how I will make my living now, and I worry for my friends and colleagues too, but I don’t really care about the future of photojournalism. The soul of it has been rotten for a while.

JC: So then there’s Magnum, which now actively includes many “fine-art” photographers. Where’s Magnum headed?

CA: I can’t say where Magnum is headed, but I don’t see the more recent additions as a radical new direction. Magnum continues to be what it always has been: a place that values the unique authorship of a documentary photographer. Did anyone really think that would only mean 35 mm, B&W photography? Magnum’s strength has always been the diversity of these voices.

By

By