A Conversation with Chris Jordan

Just a little while ago, Chris Jordan’s book In Katrina’s Wake: Portraits of Loss from an Unnatural Disaster was published. The book contains images taken in the area devastated by Hurricane Katrina, and given the contents of Chris’ earlier work I asked him for an interview.

Jörg Colberg: The first question I wanted to ask you has to do with something that I read somewhere, I think it was in another interview. You took up photography after being a lawyer for ten years. I find this interesting for a variety of reasons. For example, I think it’s good to see photographers who have not used the usual art/photography-school approach. But what I really wanted to ask you about is your motivation for the step. Given your success as a photographer, I am sure you have not regretted having done it. Would you mind telling me a little bit about your original motivation and about your experiences since the change?

Chris Jordan: My interest in photography actually goes back much further than when I left the law practice three years ago. My parents are both artists— my father is a photographer and photographic collector, and my mother made her career as a watercolor painter. So I was around photographs, paintings and art books since I was a child. I ended up in law school for all the wrong reasons, and three weeks into the first semester I suddenly developed a passion for photography. I think maybe a deep part of me sensed I was headed in the wrong direction, but at that time I didn’t have the courage to change paths, so I became a lawyer and made photography my hobby. For the next ten years I spent all of my free time and income photographing, working at night and on the weekends, making several whole bodies of work that have never been shown anywhere. All that time I knew I had found my calling, but I was afraid to commit myself to it, so I stayed stuck in a career that was unfulfilling and emotionally unhealthy. All around me I saw artists and musicians and writers and other people living their lives more fully. It dawned on me that if I didn’t do something pretty soon, the chance would pass and I would become an old person filled with regret. So I jumped off the cliff, not so much as an act of bravery but simply because I could no longer go on as I was.

JC: Your work strikes me as a bit more political since it addresses aspects of our culture of consumerism. I could imagine that you must have run into some resistance when presenting your work. Have people complained about the focus of your work?

CJ: I am frequently surprised how little negative feedback I get for my criticism of the American way of life. Maybe it is because we all know it is true: that we are living insane lives governed by materialism and greed, and we want to change but we don’t know how. Or maybe the lack of resistance is a reflection of the depth of our denial. When I exhibit my work and talk about our rampant consumerism, no one ever seems to think I am talking about them. So I get very little anger or negative response; people take my side and speak zealously about consumerism, even if they drive a huge SUV and own three homes and work evenings and weekends to pay all their credit card bills.

This illustrates for me the complexity of the issue. Talking to Americans about consumerism is like talking to someone with an alcohol problem. Our culture is in deep denial about what we are doing to our planet, to the people of other nations and the people of the future. And maybe the biggest tragedy of all is that we are in denial about how our consumer lifestyle is sapping our own spirits. It is incredibly sad to see it on such a huge scale, and growing ever broader under our current leadership. Today we are working more hours than any other society in the world. On average, Americans work three months longer per year than Europeans, who themselves work more than the people in most other countries. We are slowly killing ourselves, and we all feel it.

We look at simpler cultures in places like South America, and we crave their spirituality, their connectedness with the earth and with each other, the easiness of their smiles, their simple ways of joy and togetherness - and we feel this deep sense of longing. We know we are somehow getting screwed, that all this stuff isn’t really satisfying, that we have lost something sacred that is related to the very core of our Selves. But still we don’t act. Instead we get in our BMW’s and drive to our skyscrapers and shuffle our papers for all of the best hours of the best days of the best years of our lives so we can afford our new kitchen remodel. It is a tragedy beyond belief, happening right here in our own country, under our own noses, to our own selves. I think Americans in the first decade of the 21st century will be looked back upon by more evolved societies of the future as some of the most spiritually lost people in the history of humankind.

JC: Another aspect of investigating consumerism by means of fine-art photography is that, in a sense, you are transforming scenes of waste into photos that possess a strange beauty. When looking at your work, at times I thought “This looks very cool”, but then the caption informed me that I was looking at, say, piles of discarded cell phones, and there’s really nothing cool about that. In a sense, as a fine-art photographer, your job is a bit schizophrenic since on the one hand, you’re trying to document what our consumerist culture is leading to, on the other hand, you want compelling photos. How do you deal with this?

CJ: This issue comes up a lot in connection with my work. I think there are several levels to it. First, beauty is a powerfully effective tool for drawing viewers into uncomfortable territory. If I took ugly photographs, no one would want to look at them. My hope is to seduce the viewer with the intricate details and colors, and maybe the beauty of that will hold their attention while the deeper message seeps in. Many photographers have used beauty in this way, and it can be tremendously effective. It is a way past the defenses, like slipping a note under the castle door.

The strange combination of beauty and horror for me also serves as a potent metaphor for our consumerism. When you stand back at a distance, consumerism can look pretty attractive - all the nice shiny cars and houses and clothes and plasma TV’s and so on. But when you get up close and look at our overworked dysfunctional families, the waste streams of our products, the wars our greed is fostering, worldwide environmental degradation, toxic metals in the breast milk of Eskimo women, birth defects in the children of the mothers who assemble our cell phones in China, and so on, then you start to see that our consumer lifestyle is not as pretty as it looked from further back. I try to create this effect in my photos, where it looks like one thing from a distance and then up close you realize it is something else.

And another layer is that I am not so sure my photographs are beautiful at all, at least by the traditional definition. In my own life I am realizing that prettiness and niceness are not so attractive when they are masking something else. These days I am more interested in authenticity, even if that means facing up to some unpleasant realities about my own self and the society I live in. I do find a beauty in that, but it is a different kind of beauty; not a pretty kind of beauty, but a more truthful kind of beauty. So if there is a beauty in my photographs, maybe it is the latter type.

JC: Something I’m curious about is the following: Do people really make the connection between their consumerism and what they see in the photos? Maybe that’s a bit hard to tell because who knows what they do, when they come home from seeing the show at the gallery. But, as the artist who has attended the show openings and who, I’m sure, has talked to lots of people about the work, do you feel that there are connections made, that people start to realize “Hey, wait, this lifestyle of mine does have some serious consequences?”

CJ: People definitely do get that my work carries a dark and not-so-pleasant message about our consumerism, but I don’t have a good sense about whether my images are actually affecting anyone’s behavior. I suspect that they are not in any direct way. It’s a complex subject, because on one hand I want to be an advocate, but on the other hand I have to be realistic about my chances of changing anything. The pitfall for me is creating a personal stake in the result, allowing myself to feel discouraged if my work doesn’t seem to be making a difference. It is hard to accept that the most I can accomplish is simply do the work and put it out there, and let go of the outcome. But it has to be that way; otherwise I am staking my own wellbeing on the behavior of others that I have no control over. Plus, it is impossible to directly measure the effect of my work anyway, so I couldn’t do that even if I wanted to.

And another factor is that there are thousands of passionate people out there writing books, poems and articles about consumerism and other related aspects of our society; people are speaking about it, teaching it, arguing about it, doing art about it, making movies and writing song lyrics about it, and so on. So as a new kind of mass consciousness begins to take hold, I certainly can’t claim credit for it. My hope is just to be part of a critical mass, where the combined voice of all the concerned people out here on the fringe adds up to something that reaches the mainstream. That is happening in lots of other countries, and maybe it can happen here.

JC: To play devil’s advocate - something I have always enjoyed: What do you say to someone who argues that by converting piles of trash into beautiful photos you are actually contributing to some sort of high-level consumerism by creating art commodities?

CJ: I wish I could wag my finger self-righteously about everyone else’s consumerism, but it doesn’t take much self-reflection to realize I’m right in there myself. Not only do I benefit in a hundred ways from our consumer society every day, but my artwork is a direct part of it, and that is how I make my living. My books and prints are consumer items that people can buy. And in my printing process I consume rolls of paper, gallons of ink, electricity, and so on. When I drive or fly somewhere to talk about my work, I contribute to the global warming that I am trying to fight against. And in my personal life, despite my best efforts sometimes I cannot resist buying cool stuff. Those new iPods are bitchin and I want one. So there is an ironic aspect to advocating about consumerism, that is hard to deal with. One thing I try to do is look at our consumer society from within, instead of preaching as if I were an outsider. Preaching never works anyway, and I clearly am in no position to do it. But that doesn’t mean I have to remain mute. One alcoholic in a family of alcoholics can speak up, as long as they don’t do it in a finger-pointing kind of way.

JC: I first saw some of your photos from New Orleans in Harper’s Magazine, and I think I spent quite some time studying those images. Since then a book with your photos from New Orleans has been published. In the statement on your website you say that the “project is motivated by the same concerns about our runaway consumerism.” I can’t agree more with you on why that is. Here’s a question that’s somewhat similar to one I asked already, something that I mentioned on the blog a few times. I always feel a bit uneasy about looking at fine-art photos of disaster regions. There’s this part of me that thinks “This shouldn’t really look beautiful”, or maybe it’s some sort of feeling of guilt that I think a scene of utter destruction is actually beautiful. Have you ever had second thoughts about your New Orleans photos because of this?

CJ: I wouldn’t say I have had second thoughts, but this issue that does concern me a lot. One thing I realized early on was that making money from my Katrina project was fundamentally problematic. I am trying to live my life consistently with my beliefs these days, even if that means I don’t make as much money. For years I did the opposite as a lawyer, living as a divided person who sacrificed my principles every day in favor of making money. So last year when I realized I would be profiting from my photographs of other people’s losses, it didn’t feel right, and I had to do something about that. I talked with my wife about it and we decided to donate the entire proceeds of my Katrina project to charity. That will be 100% of the proceeds from my book, and 100% of the proceeds from all sales of my Katrina prints this year. The decision will end up costing us financially - basically a year’s income - but at least that is one way I can try to make a congruent experience out of portraying this tragedy.

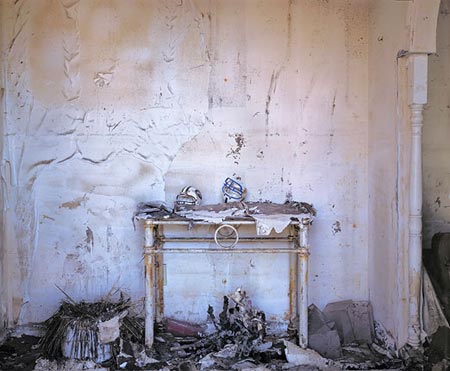

And in terms of the beauty in the Katrina photographs, there is another layer also that is worth mentioning. Just because a photograph is beautiful doesn’t mean that you have to think the thing photographed is beautiful. A photographic print, sparkling under the halogens on a white gallery wall, is a separate thing from the actual subject of the photograph. To take one photo in my Katrina series for example, I stood in a ruined living room in two inches of disgusting fecal-smelling mud, surrounded by thousands of flies, with the air filled with stinking mold and fungus. At the time there was nothing beautiful about the scene; I felt like vomiting and getting the hell out of there. But I also saw something among the nastiness that felt sacred to me. When that aspect is distilled out of its surroundings and made into a photographic print, it can be beautiful; but that doesn’t mean I think the tragedy of someone’s destroyed home was beautiful.

JC: This brings me to another aspect of this kind of photographic work. As far as I can tell, documenting areas devastated by natural disaster or wars in the past was done by photojournalists, where the emphasis is more on the ‘journalist’ part of the word. Viewers usually take photos as the literal truth - something that is very problematic, and we’ve just seen why in several cases from Lebanon (which didn’t even touch the more fundamental, underlying issues). Lately, there has a lot of fine-art photography emerged, some done by photojournalists, some - as yours - by fine-art photographers, from areas formerly only frequented by journalists. Disaster areas can now be seen in fine-art galleries. For this kind of photography I see something like the inverse photojournalistic problem: Whereas one is tempted to believe that photojournalists automatically show the truth, fine-art photography, by its nature, might be quite a bit more of a fabrication, especially since the images are shot in a way that is visually very compelling and that possesses a beauty - as you just said it’s not quite obvious what kind of beauty. Do you think it could pose a problem that people might think that fine-art photography always is, well, art and as such, at least to some extent, fabricated? For example, somewhere I saw somebody complaining about that some of the materials in the “Intolerable Beauty” series looked like they were arranged in patterns. When I saw that I thought “So what? Even if that was true, does that take away anything from the actual point made?” - but it seems to me that some people would argue that there’s a problem.

CJ: I think this relates to an evolution that photography has been undergoing, to the point where art photography today is more like painting than the traditional version of photography that people believed represented reality. It is an interesting issue because photography actually never has represented reality; it always has been a multi-layered illusion with built-in prejudices and viewpoints, just like writing or any other art form. But with photography the illusion of objectivity used to be more convincing. And with the advent of seamless digital manipulation, now even the most convincingly straight photographs can be suspect. Many photographic artists riff on these concepts as the subject of their work, but those of us who are trying to use photography as a representational tool find ourselves constantly running into the medium’s shifting limitations.

My own direction lately is to try to get away from making my work about depicting things objectively. Part of the issue for me is that our consumerism is so immense and complex that it is hard to represent it by any means, photographically or otherwise. So I am looking to evoke the tools of poetry and literature: symbolism, metaphor and the unconscious, to try to push the message beyond straight photography. The later images in my Intolerable Beauty series, for example, were set up and arranged like installations with these intentions in mind. The new series I am working on goes a step further, into pure conceptual images that aren’t even made with a camera. In one of them for example, I have assembled a huge composite image made of hundreds of thousands of copies of one tiny photograph of a Jeep that I downloaded from a website. I am not sure what to call the 12-foot-high print, but it definitely is not a photograph in any traditional sense.

JC: How have people reacted to the New Orleans photos? I saw you showed the photos in Spain, too - was the reaction there any different from here in the US?

CJ: I have found that very few people in this country are willing to face the possibility that we are accountable for the destruction of our Gulf Coast. For ninety-nine percent of the world’s climate scientists, the causal steps are simple: Katrina’s extraordinary power was caused by the record-high water temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico. Those record-high temperatures are directly attributable to global warming. Global warming is caused primarily by humans burning fossil fuels in our cars and power plants. And despite being only five percent of the world’s population, America is responsible for the burning of one third of the world’s fossil fuels, meaning that we are more accountable for the effects of global warming than any other country.

But the Bush administration, with the help of our pathetically detached media, has confused us about these issues. Most Americans believe (1) that the cause of global warming is controversial, and (2) therefore we shouldn’t do anything about it. The real travesty is in the second part. What if one group of astronomers says a giant asteroid is headed toward earth, and another group calculates that it will miss us. Merely because there are differing opinions, would we all sit back and do nothing? Or if your doctor says you have cancer, and a second doctor says you don’t, and it cannot be conclusively proven either way; would the presence of that uncertainty cause you to abandon all treatment? Somehow the Bush administration has anesthetized us into this attitude. I see and hear it in people’s responses to my Katrina work: they are willing to look at the tragedy but they are unwilling to accept any responsibility for it. And with my consumerism photos also, talking about my work often feels like an exercise in emotional passivity: viewers look at the photos and hear my arguments with appropriately concerned expressions, and then jump back in the SUV’s and continue right on with the insanity.

Showing my work in Europe this year, I found that Europeans tend to have a different level of consciousness about these issues. They are not in the same kind of denial that we are; in Europe it is cool to be a downshifter, to buy used clothes and talk about sustainability on a household level, and to advocate for a cleaner world even if that means making some personal sacrifices. They are electing leaders who are more interested in community and the environment, instead of focusing on fear, hatred and greed as the election issues. Of course Europeans are not perfect, and they still consume, but at half the level per capita that we do. And they are happier for it. The social indicators of unhappiness such as suicide, anxiety, depression, domestic violence, drug and alcohol abuse are lower in Europe than they are here, and dropping while ours are rising. Europe seems to be finding its way toward a more joyful and connected way of life, while America speeds in the other direction. Sometimes this inspires me to work harder than ever. And then other times it feels like the things I care about are being slowly plowed under by a giant unstoppable bulldozer from Wal-Mart.

JC: What I am especially curious about is what people there told you when seeing the photos. In some way, the photos are not much different from what you see in any disaster area - except, of course, that they were taken in one of the richest countries in the world.

CJ: When I show my work in this country, the comments and conversation tends to be about me, my story, and the photos: the prints, how I arranged the phones or how I composed this or that picture, what format camera I use, what I did in Photoshop, and so on. In Europe there is some interest in that also, but when I was interviewed in Madrid the discussions focused on the underlying issues: greed and denial, consumerism, commercialism and the force of marketing, the way our government is fostering environmental degradation, and so on. I heard a lot of lamentation from Europeans about the state of their own societies also, but they seem to be far ahead of us in their willingness to face up to what is going on.

In terms of my Katrina series, the jump from seeing images of hurricane devastation to talking about personal responsibility seemed to be easy for the Europeans I talked to. They didn’t get stuck at the “global warming is controversial” step, which for me it is really an issue of defensiveness. Americans saying that global warming is controversial, is just a form of defensiveness; it allows us to avoid the next step in the analysis: personal accountability, and the need to change our practices.

I also have heard the term “third-world country” used many times in discussions about Katrina. There are lots of criteria for measuring whether a particular country is a first-world versus third-world; but one of those would be whether it has the leadership and resources to respond to disasters in a humane way. Clearly America lacked both the leadership and the resources to respond adequately to Katrina. More than 300,000 of our citizens lost their homes, and a year later the majority of them still have not returned to a normal life. With that going on in our midst, I am not sure we can still call ourselves a first-world country.

JC: Going back to what you said about donating the proceeds from the New Orleans photos - and thus, donating a lot of your own money - I see your work as a fine example of how photographers as artists can produce work that does have a very strong political message and that tries to change our behaviour (I’m sure there are lots of academics who’d argue that’s true for all art, but I don’t want to go that far). When you decided to become a photographer was that part of the decision?

CJ: When I decided in 2003 to leave my job and commit to photography full time, I had no idea that my work eventually would take on an activist aspect. At the time my photography was all about formal beauty, with no real engagement in the contemporary world. I was photographing industrial color, applying a trippy theory I had developed about complex color occurring by happenstance (a kind of anti-entropy, where order is created out of chaos by chance; I thought of it as a metaphor for the creation and evolution of life). So I was exploring around industrial yards looking for colors to photograph that fit my cosmic theory, and I kept coming across these huge piles of garbage. Initially I photographed them just for their color, and then one day a friend was over at my studio looking at a print of a trash pile. He commented that the photo was like a macabre portrait of America, and that was the ‘aha’ moment that started me down the path that I’m still on. Since then I have studied consumerism, read many books on the subject and talked to people all over the world about it. The more I learn, the more alarmed I become about the enormity of the problem and the depth of our denial. Looking back to my lawyer days, I also realize how far into the trance I had fallen myself. That realization is both frightening and inspiring. If I found a path that seems to be taking me to a more connected life, then maybe I can do something to help others turn that way.

In the long run, that might be the message I care the most about passing along. To escape the insane money-driven consumer matrix we have enslaved ourselves in, you don’t have to be a saint or an altruist or even care about saving the environment at all. You can do it for the purely selfish reason that you want to save your own soul. And if my work would inspire just one person to make the leap, that would be worth as much to me as all of the gallery shows and art-world accolades I could imagine.

By

By