A Conversation with Bill Sullivan

After reading Bill Sullivan’s description of his series “3 Situations” and after looking at the images, I got intrigued and asked him whether he would be willing to talk about the ideas behind his work in more detail. I was quite excited to learn that he was happy to do that.

Jörg Colberg: In your introduction to “3 Situations” you wrote that you were “tired of the conventions in which most photographs of people are taken. And I was tired of the results that often seem to pass for poetry. I needed something to be objective.” I just have to ask this first: What’s wrong with the way portraits are usually taken? What is it you don’t like about it? Is it the process of taking portraits? Or is it the role that photographers might play?

Bill Sullivan: All of it, I was tired of all of it I guess. I wanted different conditions for taking the picture; I wanted the context to be clearly established. I think it had to do with this picture- or portrait-making space or period of time, this artificial picture-taking bubble of time that after a while I just wanted to pop. When I look at a photograph I often can’t get that kind of artificial moment that the picture was taken out of my head - that silly “it’s portrait-time moment ” or that ” isn’t that odd or interesting moment ” that you’re looking for in street photography. So with these images I tried to replace that artificial sphere of time by that of an actual situation taking place. And within that situation a scenario of events that I have designed is put in motion to create the picture… like a Rube Goldberg machine; I like designing things. Now, the results may sometimes resemble those using the other picture-making techniques but it allows for an image to be produced almost organically.

So maybe, I don’t quite trust them, the how and why some pictures are taken, I start to think of the skill of the person who captured the image, the technique, all of these things take me away from the attention that should be on the subject in the image. I wanted to make a picture that hadn’t been affected by all that, by the ego of the person making it. I wanted to stick that ego, the ego of the artiste, put that ego to work designing the scenarios - and get it away from the mug of the subject.

JC: It seems to me, though, that by deciding upon your method to take and process the photos you introduced just a different mechanism to take portraits. Isn’t that what it is? I mean sure, the subjects don’t really know that it’s “portrait taking time”, but are the results really closer to their actual selves - whatever those might be? We all put on our public faces when we go about our business, especially in a big city, and part of me can’t stop wondering what the people whose photos you took would look like if you had snapped them, say, at their favourite vacation spots? Would they look like this?

BS: I think that is exactly what I was trying to do - come up with a different mechanism for creating pictures of people. And I had hoped that this way of creating an image might make things more interesting. But I have never thought that any kind of portrait that I made as being any kind of definitive take on somebody or being able to capture the actual self of that person. What I really wanted to do was to bring the viewer closer to the subject and eliminate the typical portrait zone. I wanted to find a more direct route or connection to that person, but I never wanted to capture anyone’s soul. I have always thought that even a great portrait as being not much more than a snapshot of an actual person. People are complicated, real complicated, with many sides, faces, whatever. And these people might look different on the beach, or in the mountains on vacation, and maybe they would have on a different face.

But maybe not. It was really surprising when I came across Massimo Vitali’s amazing Beach and Disco book that shows details from his large human landscape photos after I finished taking these pictures. And it was incredible how similar the faces he captured on these beaches and in these discos, basically people on vacation, often were to the faces I captured on these elevators in the city. So maybe there really is something universal in the faces we wear.

But look, what I am really trying to say is that I think the way a typical portrait is made is in reality a theatrical production designed to create a character - or a face. And I was interested in a different kind of ‘real’ theatrical production. And I thought that this manner of coming up with a face could be interesting and at times I hoped even poetic… There is this great portfolio of pictures that August Sander made called “people who came to my door”, which was just a clear shot of whoever happened to arrive at his door, cropped always by the door frame. I think that there is something poetic about the context of that set-up… And there is also a nice work that the photographer Luc Delahaye did about 10 years ago called Portraits/1 . He would go around to homeless people that he came across in the Paris Metro and he would ask them to enter one of those coin operated photo booths in order to have their portrait made by themselves. He would put the money in the slot: they would take their own picture. The images are just perfect, the best photos of the homeless I have ever seen. And what’s great is that instead of thinking about some sensitive dude taking this great picture of the homeless with his empathy capturing someone’s soul, instead of that in your head, you have this much better dynamic scenario, a story that is in itself kind of poetic about allowing someone to take their own picture. I like that.

JC: Another - actually somewhat related - comment/question concerning what you said about the photos of homeless people. Just a little while ago, I came across something Diane Arbus said, namely that while we do hope to present a certain “image” to the camera, what the camera registers is often that something else that we don’t really want to present or that we are maybe not even aware of. When you allow someone to take their own photo doesn’t that take away a lot of what portrait photography is all about? Diane Arbus photos without the Diane Arbus in them - whatever that might be - might not nearly be as interesting. What do you think?

BS: I guess we are in the business of finding faces. And I think Diane Arbus was probably in the business of finding a certain kind of face, and she had her own way to get it - her own process or production that she used in order to get the kind of face she wanted to get.

But eventually the faces that we find or we get are tied to some kind of background or context. The context for an Arbus picture now is only Arbus - that face is now an Arbus the way a face that Picasso painted is a Picasso. I wanted the context for my faces to be the scenarios that I designed. When someone looks at one of my pictures, instead of saying ‘Arbus’ or ‘Sullivan’, I want them to ask ‘how?’ How did this happen?: how did that face get there?

I like Diane Arbus as much as the next person; I think she is highly entertaining. But, you know, after seeing the 20th soul in a row who looks like they may have just escaped from the village of the damned it starts to seem less like revelation and more like a production.

JC: Lots of photographers coax their sitters into the kind of portrait they want to see. The portrait is then really very obviously more like an interpretation of a person by a photographer than a depiction of the person.

BS: It’s true. To some extent, it is always an interpretation rather than a depiction. There are too many parts of the process that the artist controls. The artist stacks the deck and then gets to deal the cards. I just wanted to use a little bit more of a square deck to maybe make the game a little more interesting.

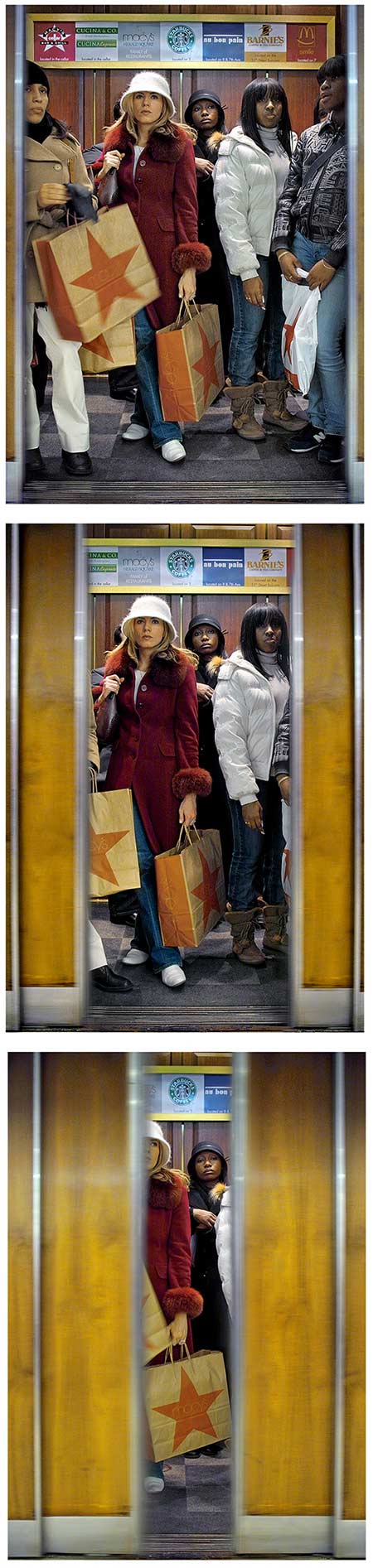

In a lot of ways I think of my work as a combination of street photography and portrait photography - I wanted to figure out a different way of combining the two. The first situation that I used was people having their portrait made in Time Square at night - a portrait within a portrait. And then with the last two series I wanted to try to do some other things. With the subway turnstiles, I wanted to make real portraits, but I wanted everyone to be defined by the same thing, the same apparatus or machine, like going into the same doctors’ office and being measured - the turnstile is like the doctors office. And then with the elevator pictures it was trying to find a way of creating group portraits.

And in the process of doing all this I also started wanting the scenarios I designed, the process, to mirror the camera or the actual photographic process itself. I wanted the scenarios in the situations function almost like a camera. In the turnstiles it is the pushing down on the turnstile bar that makes me click the shutter - and the framing is determined by the rectangle of the booth - that replaces the rectangle of the actual camera. The elevators mimic the opening and closing of a shutter on a camera and also how a picture is cropped in a cropping process. These were the first three works that I used to come up with the situational photography manifesto.

JC: Is there ever a truly objective portrait to be taken of any given person? For example, Thomas Ruff’s early portraits - that look like passport photos [picture below, left-hand side] - could considered to be quite objective, couldn’t they?

BS: I think what is most interesting to me about the Ruff portraits is that people seem to talk about them in terms of them being objective, that they look like what people think an objective picture should look like, they seem at first to lack style and they are clear and straightforward. I love those portraits and I think that they have really captured people’s imagination - I think that maybe people feel that they have or at least had the look of objectivity about them. That will probably change in time. When people see much of August Sanders work they often think it looks almost weird on purpose now or stylized. But what I have heard is that he was trying to remove most of the conventions from the portrait sitting process at that time in order to make the pictures more objective. But Sander like any artist would do brought other things into the process to make them look like a Sander as well. He introduced new conventions. Many of his portraits now look as perfect and stylized as an Ingres.

And to me the Ruff portraits also look vivid and highly stylized, again theatrical not anything like a passport photo, they remind me more of those beautiful portraits from the Northern Renaissance by people like Cranach, Memling [picture below, right-hand side] and Holbein - really strong clear faces against a simple background.

So no, I guess I don’t think it is possible to make a truly objective portrait, I am not sure I would even want to try, but maybe, maybe I could, maybe I should try. With these pictures though I just really wanted a major element in the process to be objective, and that was establishing the context.

JC: Of course, that’s another, added, complication, which you mentioned implicitly. It’s the viewer. I am certain that we see different things when we look at Sander’s photos than someone who lived at the same time as Sander, or maybe not all that much later. I have the feeling that it’s almost impossible to factor in the viewer - unless, of course, you’re doing political photography and/or propaganda where you’re aiming at manipulating the viewer - and I’m sure the viewer must have played a role when you were thinking about your photos. Or maybe not?

BS: I think anytime you edit you are probably thinking about a viewer: you are picking one photo instead of another for a reason. And separately I think that is also what a lot of street photography is about - playing around with the context. It is a game with the viewer. It tries to confuse or confound the expectations of the viewer. But I didn’t want to do that exactly. I didn’t want to play with the context: I wanted to establish it. But I am still probably playing a game the viewer.

JC: You will not be surprised that I bring up the diCorcia lawsuit. The case was dismissed, but - I think - questions do remain. But part of me thinks - and I’ve heard this from other people - that somehow, there might be something wrong with taking photos of other people without their consent and then hanging those photos in galleries. What do you think about this?

BS: I have never thought for one second of a moment that it is wrong. I always thought that it was right…. a little weird though maybe. The first of these three series I started was actually meant to do just what you are talking about. I thought it would be interesting if someone went to Times Square in order to have their portrait made and then a picture that that they sat for that night could then hang in a gallery or even better a museum.

But there are really lots of roads that you can take questions from that case down. It actually reminds me of that great quote by Lorca diCorcia himself: “Photography is a foreign language that everybody thinks they know how to speak.” People’s take on photography is just so different and probably real personal, but somehow each person just assumes that their take is objective, because deep down they just really believe that a photo is objective.

But I just don’t exactly believe that a two-dimensional image on paper is really that person, or even definitive at all - it is one angle that allows you to consider the subject. But it is my picture not an actual person stuck on the wall. It reminds me of another great quote, by Garry Winogrand. When he was out taking pictures people would often say - “hey, why are you taking my picture” he would say back to them “I am not taking your picture, I am taking my picture.”

JC: I am curious about the kinds of reactions that you have got when showing your work. I can imagine the reactions might be quite interesting. Were you surprised by how people reacted?

BS: I think a lot of the reactions have to do with time and distance. If these were pictures of people from 40 of 50 years ago, or pictures of people from some other place like some Peruvian lady none these question would apply. It is funny, I think, it seems to feel strange and maybe like a step over some personal moral line because it feels more real, so close - to our actual neighbor. The person I stand next to on the subway platform - that is my superstar… not the Peruvian lady.

It’s funny though when I tell what people what I do - taking pictures from up close with a camera that is not seen - without showing them the actual pictures I take they often look at me with a lot of suspicion, if not fear, and even disgust. But usually when they see the actual pictures that all melts away as if they were looking at a picture of a deer by the brook - an authentic picture from nature, a wildlife shot. People I think are drawn to making this kind of work as well as street photography and stuff because they are struck by how vivid the world right outside our door is, exactly as it is - but we don’t see many really real pictures of it

I guess in a way I wanted to get as close as possible to a complete stranger… must be a New York thing, I guess we all kind of love each other. But I wanted people to feel that closeness to another person, to get under peoples clothes and into their skin. and I think now when there is a direct gaze this often happens, a vulnerability that lets you in. I remember the great German photographer Renger-Patzsch saying how he was looking for an Eden-like state of innocence before consciousness when he made a picture. That’s what you often look for in making a portrait and you end up with something between that state and a mask, and sometimes the masks aren’t bad too.

By

By