A Conversation with Andreas Gefeller

Andreas Gefeller is a German photographer well known for his series Supervisions, which pushes the boundaries of photography by elevating the view point off the ground. I have been extremely interested in Andreas’ work for a long time, and I recently had the chance to talk to him about it.

Jörg Colberg: With the view from above, Supervisions, you produced an entirely new view of the world, which also differs from the bulk of contemporary photographic practice. How did you get the idea for the series?

Andreas Gefeller: It was a combination of scientific interest and boredom. But seriously: As a child I was very interested in astronomy, and I was fascinated by images of the surfaces of other planets, especially by those images, which showed a lot of details and which had been assembled by piecing together dozens of individual exposures, made by a satellite in orbit, to create a large, mosaic-style tableau. 25 years later (around 1998) I am on a picnic at the river Rhine with a friend, who is taking a nap, while I am bored. So I’m starting to survey the ground, taking photos with my Minox camera - I as a satellite and the ground beneath me as the alien surface of the planet Mars, except that instead of being hundreds of kilometers above ground, it’s only two meters. Later, when I cut the contact sheets and assemble them I note that I can really move away from the ground like something flying - not in reality, of course, but in a photographic way.

JC: There are no people in the photos - what is the reason for that?

AG: One of my earliest Supervisions images shows the sunbathing lawn of a public swimming pool, with dozens of people lying on their towels. It looks like you’re looking down from 100 meters above ground on this scene, and it’s a fascinating view. However, I thought the people were distracting and diverted attention from the basic idea of my work: The viewer’s attention always gets stuck on the people, who are too much of an indication of the actual situation; they are providing an indication of size and, especially through their clothes, of the time and place. So as a viewer you aren’t left with much space for your own personal interpretation. Because of that I never published that image, and since then I have been photographing public spaces without people - so they are hard to categorize either in time or space. I prefer to only show traces left by people. The viewer has to work towards understanding my photos. Often, you can only decipher how I created the images and what they show when you carefully study their details. I like it when visitors of my exhibitions move back and forth in front of the images, to first get the “big picture” and then to “dive” into the details.

JC: Of course, I have to ask this question, if I may: How do you take those images? Do you use a camera on a ladder? And how much work goes into the postprocessing? Or is this all a secret?

AG: It’s no secret. Just like a scanner, which works across lines on a piece of paper, I walk across a certain area line by line, and with each step I take a photo. I carry my camera, which is pointed towards the ground, in such a way that my own feet don’t end up in the images. Postprocessing requires more time than the actual taking of the photographs. However, it’s very important for me that, strictly speaking, it’s not a “modification”. The images are not changed by adding or removing something; I also do not change the scale or the placement of individual objects in them. Which makes my work hard to categorize: On the one hand it’s purely documentary, because I record the world meticulously and correctly, on the other hand the work is fiction, since I take photos from a view point, which in reality does not exist.

JC: Because of what they show your photos need a corresponding size, so the viewer can actually see what there is to be seen. The photos I saw at your exhibition at Hasted Hunt gallery all were huge, which, on the one hand, is very impressive, but which, on the other hand, creates distance from the images. A “small” size, maybe 20 inches on the side, I can’t imagine for your photos - and as much as I liked the Supervisions book, in the end I don’t think it delivers quite the same impression as the big prints. Alec Soth once described this kind of phenomenon as the difference between wall and book photography. What do you think about this?

AG: To some extent, Alec Soth is right. Some works are better suited for a wall, others work better inside a book - but hardly any artist would say: OK, my next project will be a book - what could I take photos of? First and foremost, I enlarge and present my works in such a way that it expresses the fundamental idea. In the case of Supervisions, this means fairly big sizes, because only that way it is possible to simultaneously create an overview and allow the viewer to zoom into the images “in a physical way”, by getting closer to the work (this in contrast to Google Earth, where you only have to move your finger on the mouse wheel to “land” on Earth). My previous work Soma was quite different: Sharpness and precision of detail weren’t important, and the prints are not so big, which made it easy for me to design the book. But even here the following is valid: A book is always different from an exhibition. Because of the given sequence of the images and the possibilities to create double pages (or the constraint of having to create double pages), you build stronger relationships between the images. For the Supervisions book, I tried to create an additional irritating aspect by not showing the zoomed details of an image where you would have expected them. To be honest, I now think that I overdid this a little, but the general direction was correct. As someone designing books you always have to be aware of the fact that while a book has its own possibilities and advantages it can never replace an exhibition.

JC: With Supervisions you were also very successful internationally, for example in New York. Is there a difference in how your work is perceived in Germany and in the US?

AG: It’s hard for me to say. For the opening nights of the shows, where I am present and where I thus can interact with visitors in person, I can really only see tiny differences in the questions I am being asked. However, I see that a common German stereotype appears to be true: Americans are very prone to enthusiasm and excitement, which elsewhere is often interpreted as being superficial. I actually prefer that to presumedly “cool” visitors, who prefer to stand stiffly in a corner while whispering intellectual conversations. The number of sales in the US indicates that my work is being appreciated and understood by Americans. In that sense, the US market is also important for me economically.

JC: In the US there exists the wide-spread idea that German photography is mostly hip, but also a bit too cold and conceptional. Did you run into this kind of reaction and if so how do you deal with this?

AG: No, I never encountered this, at least not in person. But it happened fairly often that I was lumped together with the Becher class, which is well known for being conceptional and visually austere etc., and which to a certain extent stands for “German” photography. In the case of a photographer who lives in Düsseldorf - and who was even born there - things seem to be obvious: This guy has to be a Becher pupil! It is usually overlooked that I never studied at the Düsseldorf Akademie (but, instead, at the university in Essen), that I don’t know anyone at the Akademie and that I thus never had an exchange of ideas, which could have influenced me directly. But I also will not deny that one is being subjected to a general mood and thus - whether you like it or not - that you are being influenced. Despite of that I aim at creating my work the way I see it and not however the American - or any other - market wants it.

JC: And in general, what would you say is the difference between the German and American photography scene? Is there something like a “German” and “American” kind of photography or aesthetic?

AG: Again, I’m sure there are differences, but it’s hard for me to tell what they are. Someone participating in both the American and German “photography scene” would be in a better position to give you an answer. I do notice, however, that the increasing number of art fairs promotes - to express it in a positive way - the exchange of ideas. Or to express it in a negative manner: People are copying each other’s work as if there was no tomorrow! As a result there is a world art market (almost) without local relations - fairs in Miami or New York look just like those in Berlin or Basel, and the only difference are their visitors. You either see always the same works by the usual suspects, or you notice that “this image looks like it was done by photographer XYZ”, or “that’s done in photographer XYZ’s style”. I furthermore think that if you wanted to objectively answer your question your own selective perception would stand in the way: You mostly notice works you are interested in - be it because they have the same conceptual background or because they are totally different. Coming back to your question of the presumed coldness of German photography: I recently noted a very good, extremely strict and conceptional body of work, and it was done by an American artist, Chris Jordan. I also like Gregory Crewdson very much - his photos are very narrative, but they are also very conceptional and cool. I could easily add other American and German artists to the list. Contrary to the stereotype, there are photographers in Germany who work in a very emotional and personal manner. In other words: I think the differences between American and German photography, which I’m sure formerly were present, barely exist any longer, or they are being covered by a powerful world art market.

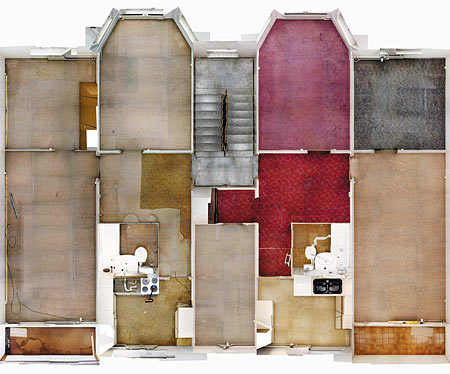

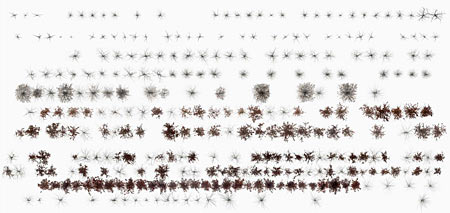

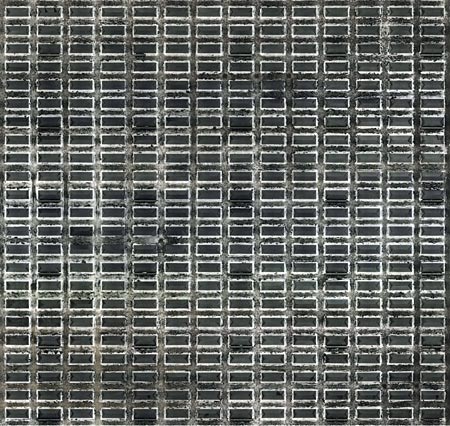

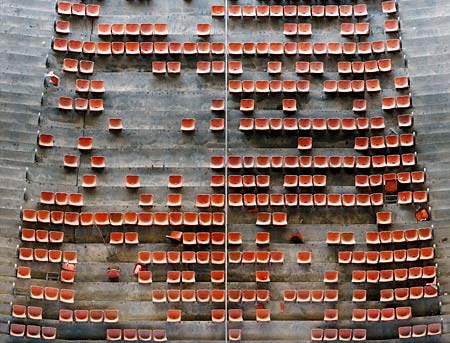

(From top to bottom, the images here show an apartment, a small area in Berlin, a tree-growing farm, Berlin’s Holocaust Memorial, leaves, and part of a stadium. It’s best to view Andreas’ work on his website - the small samples above don’t do the work justice - JMC)

By

By