A Conversation with Amy Elkins

Amy Elkins is a young photographer whose portraits I quite like. Given my ongoing quest to ask photographers about their portraits I asked Amy whether she’d want to talk about them, and I’m glad that she agreed to do it.

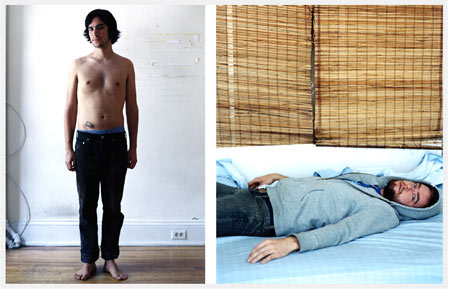

Jörg Colberg: Portraiture is, I believe, the one photographic subject that is almost infinitely hard to do. I would be interested in talking about your portraits, especially the series with the funny wallpaper. You know, the description “a portrait with the shirt off, in front of some funny wallpaper” sounds a bit gimmicky, but when one looks at your photos, they’re not gimmicky at all. In fact, your portraits possess an unusual and somewhat strange beauty. I’d be interested to learn a bit more about the series. How did you come up with the idea?

Amy Elkins: Well I’ve always been interested in psychology, in this case it was more specifically the psychology behind the way men identify with their masculinity and the way that I react/interact with them. Most of my friends are men and I suppose I naturally turned my lens towards them because they were willing to sit for me. At first there was nothing too specific about the use of wallpaper besides a desire to get away from a plain backdrop… but the more I shot with it, the more I began to realize how much each person was revealing to me and to the lens and how much the sitter was pushing/pulling against the floral patterns within the wallpaper. The sessions became these intense confrontations between the two of us where the use of wallpaper served to contrast their masculinity against something clearly feminine, forcing both of our worlds to mix for the lens.

After shooting a few I became more aware that by creating confined, intimate environments and bringing these men into them, the dynamic between the male sitter and myself was transforming something for the lens, creating what we can agree on as an ‘unusual… strange beauty’. These encounters at first all took place with the use of wallpaper, but like usual when I work on a project for any length of time, I got antsy and needed change. I began shooting outdoors in front of naturally occurring floral backdrops, playing off of the femininity of the natural world. These outdoor portraits are the newest images I have created and by far are the ones I’m most satisfied with. They were shot in New Orleans on a recent trip made to work on the project, where I went to specifically shoot men who were affected by Katrina and are still coping with it a year later.

Beyond the desire to push the background and environment in the portraits, something else began to shift in that there was suddenly a need to start shooting men way less familiar to me… a recent acquaintance, a friend of a friend, someone from my neighborhood. Doing so created an unpredictable response on both sides of the lens that caused a good deal of tension. It’s uncomfortable at first for both people involved… and then the nervous chatter settles, and it gets quiet. There’s a small window where things get very concentrated. That’s when I make my favorite photographs, especially for this series.

JC: So how do you shoot these portraits? Do you guide your models? Or do you let them assume whatever pose they want? How much do you share your ideas about the series with them?

AE: Well like I said previously, I set up in an area that forces a certain level of closeness. Beyond that the portrait sessions are comprised of three things: a backdrop, whether it’s wallpaper or what I’ve been joking around about as tapestries (larger natural environments), my model and a reflector. I don’t do much to guide them. I want their reaction to be as honest as possible and don’t want to interfere with what they are naturally giving me. They assume what’s most comfortable for them and if it’s way off I might ask them to just let their arms fall down by their side or to just relax for a moment. Sometimes they do something that is amazing and if I don’t catch it in time it almost never works to try and reenact it.

At this point a lot of the people I want to photograph are looking at my work before the shoot and are familiar with what I’ve been up to. Some of them want to delve a little deeper about the concept and I don’t have a problem sharing those thoughts. Seems often when I do it makes them more interested in participating. What I’ve discovered through this process is that people want to feel important, and that just by asking them to participate they feel that way. It’s a lovely sense of flattery. I think most people want that moment, and I love to present it.

JC: As for New Orleans, there has been quite a large number of photographers who have taken photos after the destruction of large parts of the city and during what looks like its messy and incomplete recovery. I would be interested in finding out what you, as someone who knows the town and area so much better, thinks about the photos you’ve seen. Do they reflect what is going on there? What are your personal feelings about this all?

AE: It’s usually hard to for me to look at images of the destruction in New Orleans without feeling a certain sense of territorialism. The place was my home before New York and I feel this incredible helplessness by being so far away from it. It would be near impossible for a group of photographs by any given photographer to reflect precisely what is going on there because there are so many layers involved. My favorite work I’ve seen come back is by far Robert Polidori’s, though I’m sure there are others.

I wrote this down on my most recent trip back to New Orleans. Perhaps it speaks a bit louder on the subject because it was very fresh at the time. I was feeling a bit of paralysis in terms of finding things I wanted to photograph beyond the portraits I had gone to make.

“I’ve been in New Orleans since Wednesday and have barely lifted my camera. I guess at this point I’ve no desire to be a tourist in this reality… not this one that keeps getting scoured over by photographers creating art or photo essays out of what nature already put in place for them. I’ve seen the same sunken, upside down houses, the same cars atop roofs, the same broken down realities regardless of it being in some tourists snapshot album, on Flickr, in galleries, in magazines, online, in news… it’s nothing new to me. I’m glad that people are documenting it for the world to see… but at this point I guess I’m just sick of looking at it. It’s too close to home. “

JC: As you probably expected, I also want to talk about your self-portraits. On your blog, your self-portraits are accompanied by a quote from telephone conversations with your father. Can you talk a bit about the background of the series?

AE: The build up to this series began about two years ago. I was relatively new to New York and had just begun my first year at SVA when I got a phone call from my father in California regarding some legal problems he had gotten into. At the time things were up in the air, I mean way up in the air, but it sounded like the most likely scenario would be that he would end up in prison for at least a few years. The idea terrified me but I was so far away from him and from that reality that it didn’t faze me until he actually turned himself in a year later.

The first call he made to me once there is something that would be hard to forget. It was so descriptiveÂ… every emotion, every scent, every activity and routine was laid out within the 15 minutes he had to make that phone call. My head was swarming with the imagery he had given. The 15-minute phone calls continued to come about once a week and I began turning my camera towards things I thought felt or looked similar though it was completely intangible. This series is actually on the site as well under ‘Personal Documents’ and is what led up to the self-portrait project on my blog.

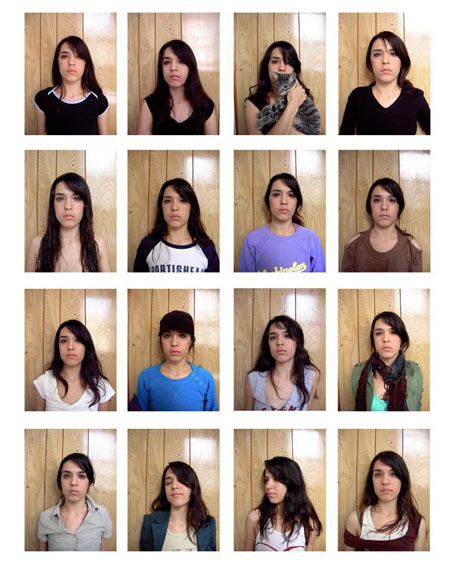

The actual series began on January 27th, 2006 when I received a phone call from my father explaining that he had been accepted into a program that would allow him to return to Los Angeles nine months later. All of a sudden I couldn’t shake what felt like a countdown. I guess for reasons I still don’t quite understand I picked up a camera and decided to create my own regiment by photographing myself every day until his release date. The portraits served to document the passing time in both of our lives. I began matching the images with excerpts from the 15 minute phone calls we were having in hopes to connect with a larger audience than just those having similar events in their own lives, transforming it from being more about the relationship we share rather than the circumstances we are dealing with.

The project was always done with the idea of installing it somewhere once completed. The blog on the other hand was there to share the process and the footwork that led me the finished piece which I’ll be displaying at one of the SVA galleries in November. It’ll be amazing to finally be able to step back from the whole project on a wall and trace the passing of time.

JC: What’s the appeal of self-portraits? And why are self-portraits always serious?

AE: The appeal of self-portraits in this particular project is quite simple. I wanted to photograph one thing daily that would be significant enough and consistent enough in my life that it would show the importance of passing time. At first I actually toyed with photographing the prints my feet made on the bathroom rug upon exiting the shower everyday because I thought it was sort of a poetic way of showing how fleeting time can be. The prints would be gone within 15 minutes but I could preserve them. I also photographed my bed in its tousled unmade state daily for a week and found that the images appear both human and perhaps even equally distressed. But I guess photographing myself during this bizarre chapter of my life felt way more real and honest… in that I’m leaving physical evidence of how those particular 269 days affected me and will continue to.

I’ve taken a photograph of myself everyday for the past 244 days. Are they serious? I’m not sure. Some days I’ve definitely had a very hard time wanting to sit in front of that camera because I feel awful or look like I haven’t slept in days. I sit there almost exactly the same every day though, just trying to sit still so there isn’t motion blur. I’ve had moments where I’m trying not to laugh and those smirks and twisted smiles exist in this timeline right along side those days where the last thing I want to do is sit in front of a lens.

JC: In retrospect, at (or near) the end of the series, what do you think about it now? Have you achieved what you wanted to achieve? Or has the series taken on some sort of life of its own - something that photographic projects sometimes (or maybe even often) do?

AE: I think it is what it is. The project definitely took a life of its own after a while and people reacted strongly to the parts of it they got to see on my blog or in person. It has always been a bit of a selfish thing, where my desire to work through something highly personal overrode the desire for others to understand it. But something I’ve learned along the way is that people respond when work is personal and sincere. I never intended for this body of work to have such a large audience, though now it seems it’s opened doors for me. I’ve had parts of it shown in a traveling group exhibition in S. Korea and was asked to work on a Nikon ad campaign because of it. Considering I never intended to achieve anything like that with it, it’s pretty gratifying.

JC: You live and go to school in New York City. I could imagine that it must be quite hard to do that. Not only is New York City one of the most expensive places to live in, there are also thousands of other photographers, both those who already made it and those who are trying to make it. How do you deal with that? I could imagine that this must be quite hard. How do you go about finding your own photographic voice?

AE: To be honest I’m not sure I’ve ever dealt with the idea that there are so many of us out there, especially in this city. I feel that I moved to New York because I was needing a little extra fire under my feet. Both California and New Orleans felt stagnant in terms of giving me an outlet for my creative drive. School of Visual Arts gave me a pretty generous scholarship and I ended up moving to NYC on a whim, thinking that if they believed in my work enough to give me a bunch of money to go back to school than I had better just run with it. I graduate in May. I guess that’s when I’ll have a clearer idea of what I’m up against.

The sea of photographers that you are referring to does exist… but I’m constantly realizing that plenty of them aren’t that good… just as plenty aren’t trying that hard. The ones that are good on the other hand only prove to inspire me and make me want to become a stronger photographer. I’m doing what I know how to do and keeping my focus on my work. I’ve never compromised my artistic vision, and opportunities keep unfolding. I’m not sure where else I could live where every resource and inspiration I could ask for is right there within reach. This city never ceases to amaze me in that regard and that makes all those other fears and competitive thoughts melt away.

By

By