A conversation with Thomas Ruff

Thomas Ruff, phg.06, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London.

Over the past few years, Thomas Ruff has exploring photography to an extent rarely matched by other artists. His latest area of exploration involves photograms. At the occasion of an exhibition of photograms and ma.r.s. at David Zwirner Gallery, NYC, I spoke with Ruff about his thinking behind these and other bodies of work.

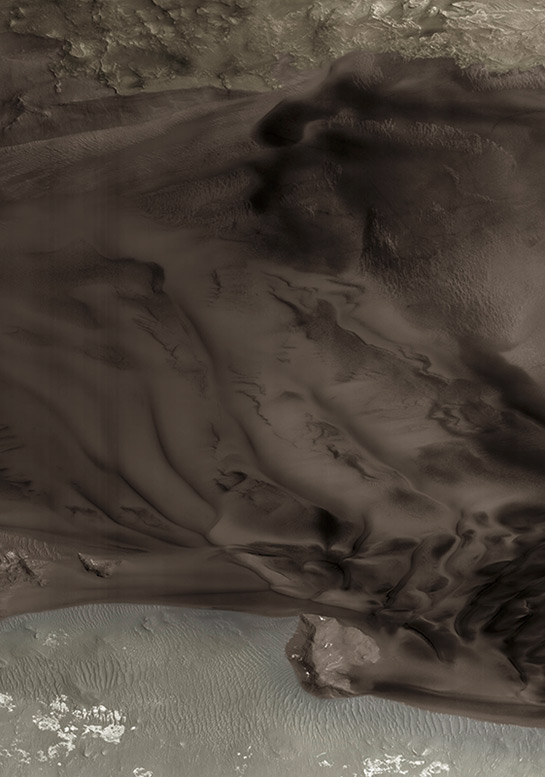

Thomas Ruff, ma.r.s.07 III, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London.

Jörg Colberg: You produced a series showing fields of stars (Stars), and you talked about how the idea was to find the most objective photograph in the world, made by a machine.

Thomas Ruff: Right.

JC: Your series ma.r.s. Is also based on scientific data that you manipulated by bringing a specific aesthetic to it. Is this for you a step back towards the subjective?

TR: Originally, ma.r.s. was made for my own private purposes. At first, I did not have the idea that it would become a new series. I was looking around NASA’s homepage, found the images made with the HiRISE camera (High Resolution Image Science Experiment), and I was blown away when I saw the image resolution. I then started to play with them.

The images come in long strips, and they’re black and white. I wanted to have them in colour. I sent an email to the people at the University of Arizona and asked: „Why aren’t you producing the images in colour?” Their response: „Too much data.” Colour would be four times the amount of data. Since they were producing so many images, this would have resulted in bottlenecks when transmitting the data.

So I added colour to the images myself. I don’t remember why, but I also compressed them, and something strange happened: Suddenly, there appeared a pseudo perspective. It didn’t look as if you were viewing from the orbit. Instead it looked like a view from a plane. As a science fiction fan I liked that, because that’s the view the first human is going to have in 20, 30 or 40 years. At some point I started thinking I had something interesting. I had between five or ten images, and I really liked them. That then became ma.r.s.

Everybody looking at the pictures tells me „Thomas, you’re interested in painting here.” But no, it’s not about painting. I’m interested in realism. The images are very realistic simply because of the precision of the camera. But at the same time, they’re absolutely fictional. I never worked on landscapes, and suddenly I had landscape images from very far away.

I also thought in these images I was dealing with a topic that currently is being discussed heavily in contemporary photography: What is fiction, what is real? The images have a bit of both. What is fiction and what is real - that’s not the main idea, but it’s also part of ma.r.s., and I like that.

JC: I was going to ask you about that, the idea of landscape photography. Scientific photographs, say the Mars rover images, in principle are landscape photographs along the lines of early survey landscape photography in the American West.

TR: That’s where it continues. On top of that, it’s also about automated photography, photographs made by robots. That’s all part of it, the surrender of authorship… Ma.r.s. contains a bit more authorship than Stars where all I did was to select the area and to do the cropping.

Thomas Ruff, ma.r.s.08 III, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London.

JC: I’m very interested in this idea. I have a science background, and scientific images are always viewed as being objective, even though in reality they are fiction to a large extent…

TR: Right, all those fake colours in astromomy, where they use the Hubble Space Telescope for the optical, add some Spitzer images with blue and green parts. Everything gets combined, and you end up with a gaudily colourful image, in which nothing looks right.

JC: Seen in that light your images are essentially also scientific photographs, with an equal amount of fiction.

TR: Would be interesting to know what the people from the University of Arizona think about my images.

JC: Did you ask them?

TR: No, I only sent them an email. I thanked them that they produced such wonderful images. They wrote back rather arrogantly „We appreciate you writing us, and are very pleased that you find our images as beautiful as we do!” [laughs]

They also have colour images on their homepage, and I asked them „How did you produce the colours? Are the images Photoshopped?” Their response was „They are not Photoshopped but the enhanced color images are processed by us to make them into color. ” [laughs]

JC: I suppose you somehow have to remove the fiction bits when you’re a scientist.

TR: Yes, probably that’s why they wrote „No, we didn’t Photoshop it. It’s processed.”

Thomas Ruff, phg.03, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London.

JC: Coming to your photograms. I was blown away by them, since they’re so good. They were produced in a computer - how can I imagine the process?

TR: At home, I have a photogram by Art Siegel. Art Siegel was a student of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s at the New Bauhaus, Chicago. It is the largest photogram I had ever seen. It’s about 20” by 24”. I had been walking for two years past it, and at some stage I thought “Oh, photogram… Maybe that would be something for me.”

I then started thinking about how to do it. I quickly realized I didn’t like the limitations of the analog black and white darkroom. First, there is the photo paper, the black and white. You put objects on it, which you then have to remove, you have to develop the image, and then you look and find “Crap. This piece should have been moved a bit over to the side.” I also didn’t like that the format was fixed straight away. And I didn’t like that it was an original image. I don’t like that either.

JC: Why? I’d really love to hear more about that.

TR: There’s a quote by me from the 1980s: „There have to be at least two copies of a photograph, otherwise it’s not a photograph.” I mean when a photograph is an original image, it’s not a photograph for me. There’s the negative, and the negative is the original source. Initially, I also thought the edition size was going to be determined by demand. My gallerists quickly exorcised that thought: “No, no, Thomas, you have to have a small, exclusive, edition.” I figured out quickly that the issue of editions has to do with collectors’ vanity. If they don’t have or get an original, then at least they only want to be one out of three, four or five people. I got used to that. That’s why I think a photo has to exist in at least two copies. Otherwise, it’s something else, but not a photograph.

JC: The question really is how you would do that with a photogram where you don’t have an original in the sense you just talked about, where the object itself is the photograph.

TR: All those limitations and the b/w darkroom I didn’t like. I started thinking about how I could do it, how I could make a photogram. It quickly came back to using Cinema 4D again, which I used for zycles. I thought that one could or should or might want to make photograms in a virtual darkroom.

At that time, the program was too complex. I went to look for help from a 3D image expert. We started thinking about how to set things up. It’s relatively simple: You have a piece of paper “at the bottom,” a camera “at the top.” Additionally, we have objects, virtual objects that we created. We can place those above the paper. We set up lights. Since we’re in a virtual darkroom, we can work with colored light. So I was able to add colour to the photograms.

We started out analyzing photograms by Moholy-Nagy, and we looked at whether or how to re-construct them. In some photograms, there are lenses or a Bauhaus tea filter, which they often put on the paper. We constructed paper spirals and other spirals that we can place on the paper. The shadows of the objects on the paper were then rendered.

Thomas Ruff, phg.08, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London.

JC: Ray Tracing.

TR: Exactly. In this case, you initially get a reversed photogram, because the light sensitive photographic paper inverts when being developed. We initially only had the shadows. When we inverted them we got a photogram.

If you build an object in the virtual darkroom it does not yet have any kind of surface. For the rendering you then have to define the surface. You can use non-reflective cardboard, you can use glass or chrome as materials. With the cardboard material, you get a shadow. When you take glass, you get the refraction. When you use chrome you get a shadow and the high glossy object also reflects light onto the paper. Depending on the shapes and the material of the objects the results are quite different.

So we spent more than two years working on all the details. The biggest problem that occured was rendering the images in the right resolution for the large size photograms. We have three MACs that can render together, but for one large image they needed a week.

JC: For one photo?

TR: Yes. And you then can’t work any more with the computers. They were so busy rendering the image that we were unable to use them for anything else. So we asked an acquaintance who builds computers for students: “We need six PC´s. Add only what is needed for rendering, nothing else.” Those computers aren’t quite as fast the MAC´s, but the six of them render a photogram in four days. That’s doable. For this exhibition at Zwirner the plan was “We need 12 images in three weeks.” That got exciting. [laughs]

Of course, photograms should look like photograms. The goal really was to reach the quality of a beautiful Moholo-Nagy or Man Ray. A separate problem the 3D software caused was that the images were too perfect, too slick, too glossy. We had to work on adding some mistakes so it would look more from this world.

I wanted to create the next generation of photograms, size-wise and adding colour. Of course I looked around to see who had made photograms over the past twenty years. I found some artists that were working with the technique of the photogram, but their images didn´t remind me to the photograms I had in mind.

I really wanted to achieve this beautiful aesthetic from the 1920s. Of course, it’s absurd to use 3D technology to make nostalgic photograms. But I simply wanted to know whether I would be able to do that. For the next photograms we can try other things.

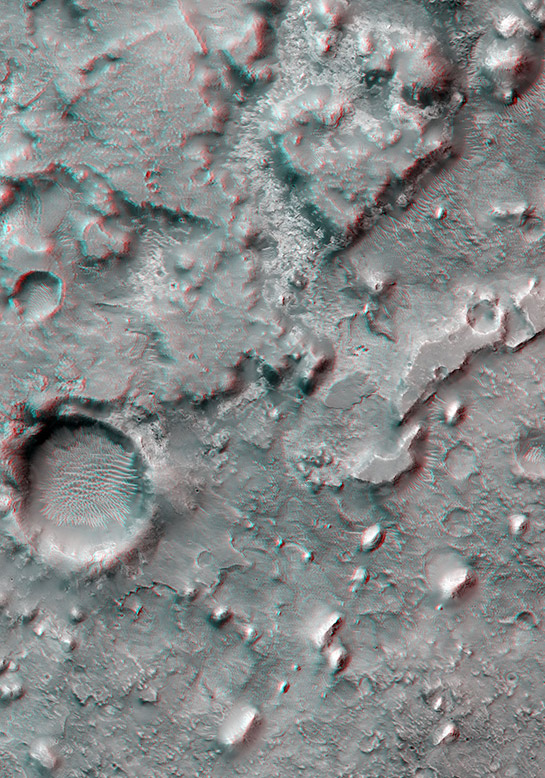

Thomas Ruff, 3D-ma.r.s.08, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London. (3D image - use colour-filtered glasses to experience effect)

JC: That appears to be a topic for you again and again: Can I do that? How can I do that? This approach to working experimentally.

TR: Yes. With Andere Porträts (Other Portraits) I had a similar problem. I wanted to make superimpositions of faces, but I didn’t want to work with a computer; I thought that would be to easy. I wanted to do this in an analog fashion, not using double exposure/negatives in the darkroom. Instead, I wanted to press the shutter button once and get my picture. I then found a camera, which allowed to superimpose two faces via mirrors so that with one click I got my picture. That was analog.

I am not very eager to explore technology. But unfortunately often when I have an idea the technology does not exist. So I have to build it myself somehow. Of course, I would be glad if I could just go out with a big digital Nikon, click! and the image is done. [laughs] That would be great.

JC: That makes it exciting when things can’t be had simply.

TR: Sure, but sometimes I wouldn’t really want to have the problems that I end up having. [laughs]

JC: When I look at your work I see how image sources, the way images are made, is becoming less and less important. First cameras, then looking on the web, looking at scientific sources…

TR: Yes. I think the most important factor is the resulting image.

JC: And process itself?

TR: The process is an unavoidable part of the work. But the main focus is my curiosity to create a specific image.

JC: Does this mean that in one, two, three or fours year’s time you can imagine working with a camera again?

TR: Absolutely. I don’t have a preference for any technology. If there is need for my analog 8 x 10 inch view camera, I’ll pick it again.

JC: Or you might just use your Canon G12.

TR: Or any digital camera. If there’s no other camera available of course my cell phone is another option, but only if I need bad quality images.

Thomas Ruff, 3D-ma.r.s.11, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London. (3D image - use colour-filtered glasses to experience effect)

JC: One final question. I don’t know whether this is a specifically American discussion or whether this is also being talked about in Germany. But there is a lot of talk about how we are being flooded with images, that there are too many photographs. Would you agree?

TR: That’s probably true.

JC: Too many photographs?

TR: Too many photographs… No. There cannot be too many photographs, just like there cannot be too much information. The problem most people are facing is how to select: What is important, what is not important? If you preserve your ability to select, there can be as many pictures as there are, you simply pick the ones that are important for you. Those remain, the rest rush through.

JC: I suppose I needn’t ask this question, but for you as an artist does it matter that there is this flood of images?

TR: I think that when I see a good photograph I recognize it. When I was teaching at the art academy, however, I knew students who ran around with their digital cameras. They’d fill their memory cards with pictures, and they then had a problem deciding which image was good, which one was bad. I don’t know whether that was because they never learned how to make such a decision or whether they conceptually refused to make a decision. But for them it is a big problem to deal with the flood of images and to make decisions.

JC: The question then is: How do I make decisions? How is that done? Are there strategies? How can one go about this, given the flood of images?

TR: It’s best to be broke. [laughs]

It’s that simple. That’s what it was for me. When I was a student I used a view camera. A 4 by 5 color negative cost three Deutsche Marks, development was another three Marks, and I was able to do the contact print by myself for 10 Pfennigs. That meant that each time I wanted to take a picture I had to very carefully think about whether I could spend the six Marks. I always took just one image. It’s likely that helped me to work very precisely. Now when you work digitally…

There’s this story about Charles Wilp, the advertisement photographer, who was asked to shoot an campaign for Bluna. He shot the campaign; and then didn’t look at the results. He simply handed the undeveloped film to the agency telling them “There’s something on the film for you.”

I don’t know whether I learned how to work precisely and in a concentrated fashion because I had to be very careful with money. I don’t know whether that’s why I still can tell the difference between a good and a bad picture. Had I been able to spend thousands of Marks, I don’t know… It’s a guess, I don’t know whether that’s what it was.

JC: If I imagined I’d be a lay person and know nothing about photography, would there be criteria for me to deal with the flood of images? Or would I have to rely on curators or bloggers or whoever else, people who’d tell me “OK, now this is interesting.”?

TR: I think it depends on the person. Some people might just possess the gene that allows them to recognize good pictures. They don’t need any help. They recognize things on their own, or they have such a specific interest in images that they are able to make a selection that is right, important and interesting for them. When you want to be competent in all matters it’s likely you’ll end up with a kind of Bouvard and Pécuchet knowledge. You’ll still have to look what other people think. No, I really have no idea what to suggest.

This interview was conducted in late March 2013 at David Zwirner Gallery in New York City. English translation: JMC. My thanks to Julia Joern and Kim Donica at Zwirner Gallery for their help, and especially to Thomas Ruff for being part of this. All images are courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York and London.