Review: Pirelli Work by Chris Killip

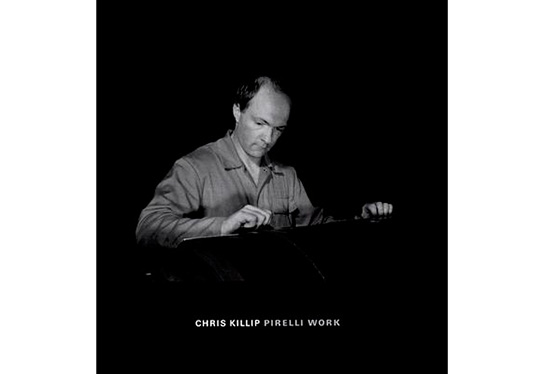

Mention the company name Pirelli in the context of photography, and most people (especially men) will probably think of the calendar right away. (Given this is the early 21st century, every time a new calendar is released I’m wondering what happened to the idea of the sexes being equal.) In 1989, the company hired Chris Killip to photograph, no, not naked “supermodels,” but workers in a factory. The resulting body of work was published as Pirelli Work a few years ago, one of those (many) books that I simply missed. I found it the other day, literally found it - a pile of books at a book shop.

At the risk of using an overly seductive cliché: If any book, this one asks for it to be seen as an object, given that the people in the book, the workers, are engaged in the process of making something. But it’s not just that, it’s also the Steidl way of printing books, which, I think, does not do every body of work a great favour. This one, however, is made to shine. For the most part, the photographs are grimily crisp and heavy - much like, one would imagine, the interior of the factory itself.

The photographs themselves are portraits - workers engaged in doing whatever their job is. Two modes appear to dominate. There are portraits framed close in, focused on the workers in such a way that they almost jump out of the frame. The second major group has workers framed by the machines (or by parts of them) - the worker usually becomes a face somewhere in the picture, surrounded by machinery, a veritable cog in the machine. This second group makes the viewer feel as if one were looking straight into the bowels of a machine, a machine swallowing up the men that in actuality control them.

Killip’s ability to create stunning compositions truly lifts this body of work to an astonishing height. And the book might be one of the last photographic hurrahs to an era long on its way out in large parts of the Western world - the era of things actually being made by people.

Whether or not there is something to be said for this kind of labour would be a topic for a long discussion. What seems fairly obvious by now is that these kinds of jobs are gone, and replacements often have not materialized - you don’t go from operating a machine to selling derivatives.

There always is the danger of mythologizing jobs that are gone as something that they were not, and that’s certainly not something I want to do. I don’t think Pirelli Work invites the viewer to do that. Instead, it manages to portray these workers in an emphatic light, focusing both on the skills needed to operate the machines and on the workers themselves, individuals going about a job.

It would be interesting to see this work next to other photography from the industrial age, photographs of workers in factories, focusing not just on the aspect of work itself, but also on how it was approached by the photographers in question. Provided you have the right photobooks at home a lot could be learned both about the nature of work itself and about how photographers viewed it.

Pirelli Work; photographs by Chris Killip; essay by Clive Dilnot; 128 pages; Steidl; 2008