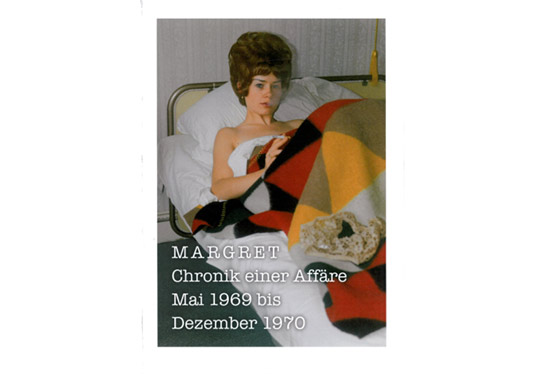

Review: MARGRET - Chronik einer Affäre

A married businessman has an affair with a married woman, his secretary. She is in her early twenties, he is approaching forty. In principle, there is nothing particularly noteworthy about this. As it turns out, things appear to be a ménage à quatre with two non-participating partners, since the man’s wife knows of the affair (he has to make his wife apologize to his lover, who had been called a floozy and now threatens to withhold further sex), and the woman’s husband might or might not be aware of what’s going on. We know all of this because the man decides to document their affair, taking photographs and collecting material, such as restaurant menus, train tickets, hotel bills, some of her hair (pubic and otherwise), some of her nail clippings, even a scab from her wrist. On top of that, the man writes a diary, using a typewriter, chronicling events: When and where they go and/or meet, the various photographs taken, their love making, and more. Decades later, the material is found in a black suitcase, sold at an estate sale, somewhere in Cologne (Germany).

Unlike most other forms of art, photography lends itself to this kind of obsessiveness. You take a picture so that you have it. In this digital day and age, the materiality of the photograph has been vastly reduced1, to have sheer quantity replace physical quality. But the general idea has remained what it always was: A photograph is a fetish, something you take to possess, a process that makes the idea by “primitive” cultures that the camera might steal part of your soul more apt than it might seem. Seen in this light, the call for more curation in a world flooded with photographs also is a call for this fetishism not to get lost2.

MARGRET - Chronik einer Affäre, the book containing the photographs and materials collected by the businessman, makes what might sound like overly theoretical ideas about photography very obvious3. I am not a robot, Margret (the woman’s name) at some stage complains to her lover who, it must seem to her, is a bit too interested in having sex. But the sex aside, she has a good point because she is treated like one, or maybe more accurately like a sex object, a fine specimen4. Reading the man’s writing (which gets more and more obsessed as time passes) one can’t help but notice how he is utterly blind to the fact that while his lover very obviously is a very interested party in going on trips, getting things bought, and having sex in hotel rooms, she is also growing distant from him. The photographs never cease to showcase her, and that means: her body, like a trophy5, but her facial expressions slowly change, from being flirty to being confident and tired of her lover. The last note describes what might have been their final encounter as lovers: “No photographs,” sex, plus some spooning (“from 6pm until 6:30pm”).

The viewer has no way of knowing the extent of curating or editing that might have gone into the making of MARGRET. We need to keep this in mind. Just like we can’t know what exists beyond the frames of photographs, we don’t know what exists beyond the edits in photobooks. All photography is fiction, at least to some extent. Whether or not we believe that these photographs are documents are indeed real doesn’t matter nearly as much as those aspects of photography they tackle: The fetishism of photography, caused by the medium arising from our desires, and the kinds of stories you can tell yourself by taking photographs, creating your own fictitious world, which looks oh-so real.

MARGRET - Chronik einer Affäre; collected materials and photographs; essays by Veit Loers and Susanne Pfeffer; 142 pages; Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König; 2012

1 The photograph as a physical, treasured object, as a fetish essentially, survives on the walls of families or wealthy collectors, and on mantle pieces or desks.

2 Of course, collectors, editors, and curators going through vernacular/archival photography are driving the point home most forcefully.

3 Unfortunately, the book has only been published in a German language version only.

4 To be correct, the viewer gets to see Margret in the nude only a few times. For the most part, she is wearing clothes/underwear.

5 Isn’t that what makes the paparazzi culture so noxious: The fact that paparazzi turn especially (mostly young) women into little more than hunting trophies?