Review: Metsästä by Anne Golaz

If there was one shortcoming I’d need to point out about Metsästä by Anne Golaz it’s the conversation with Nathalie Herschdorfer and Anna-Kaisa Rastenberger at the very end of the book: It’s pulling away the curtain. Once I realized this, I stopped reading straight away. If there is magic to be had - as there is - let there be magic. Don’t let the curators take it away. On her own website, the artist describes Metsästä as follows: “It is a work partly autobiographic, fictional and documentary, a story both chilling and amazing, where men are hunting missing preys, devoting themselves to magic and decadent rituals, while female carachters [sic!] become fascinating and timeless icons.” People want descriptions, people need descriptions, and this is a good one. The little essay by Golaz in the book is even better.

So there is Metsästä, on the surface a collection of images, using varying styles. The book does the right thing: The first page reads “From the woods” (the translation of metsästä), and on the second page the viewer is thrown right in: A man is seen, seemingly moving towards the viewer, yet at the same time turned away, against a sea of darkness. That darkness is going to be a recurring theme throughout the book, people or things embedded in it.

“Then this forest,” writes Golaz in her short essay, ” its bleak vastness all around like a dark green silhouette made of cut lace. And beyond that, there was mainly the challenge of measuring up to this yawning abyss of freedom.”

This yawning abyss of freedom - that would be an apt description of the medium photography. It might not be that coincidental that as the sheer number of photographs made every day is exploding, photobooks are becoming more complex, combining photographs that previously would have been carefully kept apart. Redheaded Peckerwood by Christian Patterson provides a well-known and widely acknowledged example, and Metsästä falls into this same mold.

In a certain way, photographers like Patterson and Golaz are now acting not only as photographers. They have, at least in part, become their own curators, carefully mixing up styles and tropes. In that sense, it might not be entirely hyperbolic to say that there are new John Szarkoswkis among us: They’re just not working as curators in museums. Instead they’re working very closely with their own medium, with what they create; and the photobook is their (natural?) outlet (while museums have long moved far away from the idea of presenting photography in cutting-edge ways).

Just like Redheaded Peckerwood, Metsästä explores the way a photographic narrative can work; but unlike the partly fictionalized crime story, which is based on a true story, Golaz’s book remains firmly embedded in the artist’s own psychological space. Where Redheaded Peckerwood often borders on the clinically cold, Metsästä is able to produce actual chills; where Redheaded Peckerwood offers the solace that the story happened a long time ago, Metsästä might be lurking somewhere in the dark: Both are photobooks at their very best. Highly recommended.

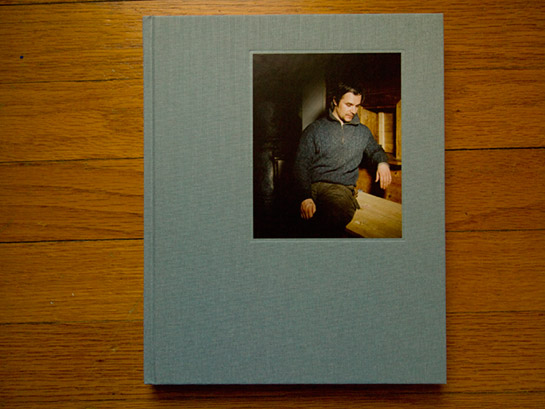

Metsästä, photography by Anne Golaz, conversation with Anna-Kaisa Rastenberger and Nathalie Herschdorfer, 120 pages, Kehrer, 2012