Review: The Graves by Eric Stover and Gilles Peress

Photography is great for what used to be its original purpose for a long time, to essentially say “this is that.” You take a photograph of something, put it in the center of the frame, and then this is that. There already is that small step people make, namely to assume that a photograph of something is the same as the thing itself. All of that has worked wonderfully well for many years, and it still does, at least to some extent. Photojournalists, in particular, have relied on the “this is that” mechanism for such a long time that they didn’t realize that you can play this kind of game only for so long, until people stop looking. You see, people aren’t stupid, and they also need to protect themselves. I think it’s fair to say that the time for the this-is-that game is up in photojournalism now (while the business model is imploding itself), so there are all kinds of attempts to re-play that game, by trying to make it look cool (using Instagram, for example). That’s not going to work.

I had to think of this complex when looking at The Graves: Srebrenica And Vukovar by Eric Stover and Gilles Peress, a book that came out in 1998 (thankfully, the book didn’t make it into any of the books about photobooks, so it’s still very much available and affordable). I found a quote by Peress on this website (which probably isn’t even the real website any longer): “I don’t care so much anymore about ‘good photography’; I am gathering evidence for history.” Eeerrr, OK. Photography can in fact serve as evidence, maybe even as evidence for history, but its ability to do just that is quite limited. As much as I like the book for what it does and how it talks about the issue, it’s a great example of how the “this is that” approach works well in some ways and fails badly in others.

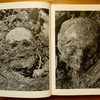

Large parts of the book are concerned with the excavations of mass graves in Srebrenica And Vukovar, two towns that - like many others in former Yugoslavia - suffered the misfortune of being subjected to leftover business from World War 2, done with World War 2 methods: The mass slaughter of large parts of the population by crazed militias, in the name of a crazed ideology, but also involving religion - Muslims and Christians, thus foreshadowing the ever more volatile wars of our current times. Large parts of the book talk about and show either the excavations or their results directly, and this is what photography is great at: This is that. There are two boots, with the broken-off bones of its former owner still sticking out of them. These are skulls. This is a big group of corpses. This is the evidence for history. Photography does this well: Despite the fact that the boot or the skull or the group of corpses is turned into an image, the viewer still immediately gets the point.

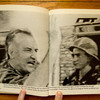

Things get rather more complex when photography tries to show something that is not there, or maybe that is there, but for us to describe it we’d use a more abstract term. Think about an emotion, for example. Photojournalists have, of course, found ways to work with that, too (as have other photographers). To show grief you show a grieving person. Now there’s nothing wrong with that approach - apart from the fact that it lends itself to cliches, and that the issue of theatricality arises. Another way to describe the problem would be to say that a single photography might not be the best way to express or convey emotions. Emotions are very, very complex things (don’t we all know that?), so how can we expect them to fit into a single frame? On top of that, unless there is considerable theatricality, different emotions can look the same, or they can resemble gestures we do in very different contexts: Is that person very sad or is that person merely trying to remember something very important? Or is the expression on that person’s face merely whatever was there for a split second, extracted to serve a purpose?

The last part of The Graves: Srebrenica And Vukovar demonstrates that problem very clearly, in particular since up until then the content and the “this is that” approach aligned so nicely. But now we’re asked to see all these things in people’s faces, to read images in certain ways - images that look like they were made to contain the abstract “that” in just one frame. It’s not that photography cannot express anything more complex, but I don’t think it can do it in single frames (or in collections of single-frame images). Instead, it needs to work with its own inability to do certain things, and then it needs to trust the viewer (who, let’s face it, is smart enough) to figure it out.

That said, The Graves: Srebrenica And Vukovar definitely is a book you want to look at, a book you probably want on your book shelf, whether you collect photobooks or not. After all, it shows what people are doing to each other, and the madness has not stopped since the wars in Yugoslavia. We have not learned out lessons (which makes me think that collecting evidence for history might not be enough, and it also makes me wonder about the supposed power of photography). But maybe we will learn them if we keep trying. And that’s the ultimate fact about history: History itself, just like the evidence, is useless unless we make an attempt to learn from it.

The Graves: Srebrenica And Vukovar, photographs by Gilles Peress, text by Eric Stover and Richard Goldstone, 333 pages, Scalo, 1998