Review (of sorts): Interrogations by Donald Weber (in actuality an investigation of the shoot-the-messenger syndrome)

Book Reviews, General Photography, Photobooks

MORE IMAGES

When we say that photography is cruel, do we not say that photography itself lacks the mechanisms we have put in place to shield us from what is all around us, from all those unpleasant things?

I had been aware of Donald Weber’s Interrogations for quite a while. But given what I had seen about it online I had developed absolutely no interest in looking at the book. The work - and the ensuing debates - just felt too obvious, too much along the lines of what one could expect. A few days ago, at a bookshop in Amsterdam a friend urged me to look at it anyway. Imagine the very pleasant surprise when the work turned out to have much more depth than I had expected - after having seen the mostly sensationalist brouhaha online. As a matter of fact, flipping through the book (before buying it) I thought that the images I had seen online were for the most part the weaker ones (of course, they were the more sensationalistic ones, too). Plus, I don’t think I had seen there actually is a prologue in the book (see the photographs of selected spreads).

So I ended up buying a copy, and I started thinking about all of that. How good is the internet to showcase photography? And how come we always run in these circles where some debates pop up over and over again, even though there never really is a solution? Of course, I don’t have any good answers.

On my flight home, twelve kilometers above the icy Atlantic, I started writing about the book, and my piece quickly turned into an investigation of what I’d call the shoot-the-messenger syndrome. We’re all aware of it, and any photojournalist reading I’m sure is particularly aware of it: If confronted with harsh photography, let’s just blame the photographer for being there, for making those photographs, or let’s talk about how photography is cruel. Why is that? Why those debates? Why don’t we instead talk about what the photographers are actually showing us. Here’s what I came up with:

The first step of torture by the Inquisition involved inflicting no physical harm whatsoever: Instead, the victim was made to see the instruments of torture. In a somewhat related fashion, during the high times of the purges in the Soviet Union, groups of people were tortured all at once: One random person underwent the physical process, the rest were made to watch. Seeing, watching was often enough.

Photography has the ability to operate in much the same way: Seeing a photograph is what makes people react. Donald Weber’s interrogation photographs show subjects that very obviously were being caused great distress. We all know those things are happening. We know that people are routinely being abused, and not just in places very far away, but also very close to home, often even in our name (Guantanamo Bay comes to mind, as does the absolutely atrocious treatment of Bradley Manning). But we don’t see. And if we don’t see something, it’s not really happening.

Of course, we could read about it, but reading does not offer the immediacy of seeing. Getting information through the written language is a process that deals with the intellect first and with feelings second. The brain has to translate the shapes on the paper or computer screen into something we can understand or feel. There is enough of a delay for us to interrupt the process or to have our intellect interfere. Photography, in contrast, is the equivalent of those shapes, and the processing comes second. All we can do with a photograph is to make it go away and to hope that it has not imprinted itself too thoroughly into the visual center of our brains.

Photography essentially is a feel-good exercise for ourselves: We look at photographs to feel good. We want to feel good.

It is important to realize that this is usually true even when photographs make us feel bad: it is precisely the fact that we know we should feel bad that can result in our enjoyment. Of course, we would never be able to admit that, because it would make us feel bad. Often, it would amount to what George Orwell called a thought crime. In our society, there exists a very clear set of things that we know one feels bad about, regardless of whether one actually does or not. The label applied to some of the mechanisms that deal with those topics is “political correctness.”

The problem with political correctness is not that it is tries to solve problems that don’t exist. Make no mistake: Sexism, racism, homophobia, animal abuse - those are very real problems. But political correctness doesn’t offer much - if anything - for anyone who doesn’t agree 100% with the politically correct solution to find a way to deal with the problem other than pretending there is such a 100% agreement. What is more, political correctness is so rigid that people who in actuality do have a problem with a topic, but are not aware of it, do not have a chance to realize the conundrum they are in. Thus, political correctness does not actually solve any problems - it merely pretends to do so, while creating a fairly large amount of both resentment (typically on the political right) and smugness (typically on the political left), both of which are poisons for the general political discourse.

In our society, there also exists a set of things we know one feels good about, regardless of whether one actually does or not. Examples here include patriotism, the fact that we live in a democracy, the free market, etc. These issues are less well-defined than the ones that are covered by political correctness, and they differ more between different countries. Two countries might agree on each and every aspect covered under political correctness, but they can easily disagree on the required amount of patriotism, say, or on the required amount of faith in the free market.

It should be noted that on top of the things society requires us to feel good and bad about we all usually have even more topics that fall under either category, as a consequence of us belonging to certain groups, however large or small they might be. For example, I’m a firm believer in animal rights, so I don’t eat meat. Nobody is perfect, though: I will eat fish, even though I try to limit my intake. Of course, I could be a vegan, but I’m not, because I like milk products (ironically, I’m lactose intolerant) and eggs. As a consequence, I am quite intolerant of hunting, even though I have heard more than once that some kinds of hunting are actually necessary to control an animal population that has been long thrown out of whack by hundreds of years of human intervention in Nature. Even within this subculture of people who have stricter rules about animal welfare than society, with these various details I’m at odds with a surprising number of people. I’m essentially behaving incorrectly for vegans and real vegetarians (who won’t eat fish), while, at the same time, I’m part of a group of people who often pride themselves on being more aware than your average person (whether or not that’s true is not so obvious).

The reason why I brought this up is not to bring attention to myself and my choices. The main point to realize is that we all are subjected to various rules and stipulations going beyond the big topics. Whether we agree on the topics (and how to deal with them) is actually quite irrelevant. What does matter, though, is that as a consequence of the rules we have imposed on ourselves (and/or have allowed to be imposed on ourselves) we do feel good or bad about certain things. In other words, if you, the reader, disagree with me, the writer, completely, about each and every of the rules I (or you) take for granted, we still both will react to photographs in similar ways: Weighing them against what we believe in (and/or what we need to believe in).

As a consequence of us knowing that there are things we are essentially required to feel good about and bad about, we have mechanisms in place that determine large parts of our behaviour. Bringing this back to photography, the presence of these types of mechanism means that when we find that a photograph triggers the correct or desired reaction, we feel good, even if the reaction itself amounts to feeling (or pretending to feel) bad.

These mechanisms pose severe problems for photography, at least as long as you believe that photography - just like any art form - should make us feel something, should make us question our believes, so that we either change them or find even more faith in them. If a reaction is essentially predetermined because any alternative reaction would cause societal sanctions, how can photography then deal with topics that fall under such categories? The more severe the sanctions, the less breathing space there is for a photographer.

Things get considerably more complex once there are cultural differences. A very good example to illustrate this problem is provided by Nobuyoshi Araki. It seems safe to say that if you are Japanese your reading of the photographer’s images of ((semi-)naked) women tied up will be vastly different than if you are American, or if you are German. Different countries have very different ideas of what is considered pornographic. What is more, different countries have very different ideas of what is considered to be acceptable pornography (it is very worthwhile mentioning that as far as I know child pornography is very strictly prohibited all over the world). Add to that the very different ideas of the roles of men and women, add to that the general idea that different cultures have different roles, which we need to be able to appreciate (or maybe not?), and Araki’s photographs become very loaded outside of his native Japan. How does one deal with this problem? As a Westerner, do I reject Araki’s photographs of tied-up women because they might be too pornographic (the German in me disagrees, the American in me is sympathetic to the idea), because they might be too misogynistic (the German and American agree, with both realizing, however, that there is a sizable BDSM scene in the West); or do I need to accept those photographs because they come from a different culture, and rejecting them would amount to cultural imperialism? Or maybe even if I want to accept them because I don’t want to be a cultural imperialist, they are still misogynistic - so then what? Simple reflexes do not help us tackle these questions.

We thus have arrived at a point where some topics have become such a minefield that any photography that does not illustrate the required and/or simple way of thinking risks causing confusion if not severe societal sanctions. As a consequence, a lot of photography done around those topics essentially has become completely useless in an artistic sense. Instead, it has become a feel-good exercise - you get to see what you already believe in.

Photography that genuinely makes us feel bad, without there being a way to feel good because feeling bad is what we consider to be correct reaction, falls outside of the mechanism I talked about above. Here, we are confronted with photography that offers us the chance to truly experience photography for what it can be: A very powerful visual force. But of course we do not want to feel bad. Nobody wants to feel bad. And there might be a second part of feeling bad, when we realize that we feel bad because of what we see, and because we think we could have done something that might have prevented what we see, or because we know that despite what we see we are not going to do anything. That’s why we often react so strongly to this kind of photography, especially once it deals with something that is happening in a public context: We’re forced to have feelings that are in conflict with our own behaviour. It’s photography that, if we were honest, unmasks us as hypocrites.

Photography has long struggled with this complex, too. This is the area where the term “compassion fatigue” was invented. This is where photography is talked about as being cruel. This is the area where photographers are being abused for their unwillingness or inability to do something about what they photographed. Much has been written about this area. My first reference here would be Susie Linfield’s amazing The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence, a book that delves deeply into many of the aspects, while, at the same time, questioning the writing of authors like Susan Sontag.

Most of the writing in this area centers on photography itself or on photographers. But it feels odd for me to stop there. Photography itself, on its own, has no meaning. Photography, no doubt, does all kinds of things, but it does these things when it is being used by people, when it is being viewed by and talked about by people. And when I use the term “people” I mean people other than the photographer.

Take a photojournalist. A photojournalist might take photographs, but before we see them there usually is a photo editor who might or might not answer to all sorts of other people, other editors, who, in turn, might or might not answer to even more people, say the people who work in the business department and who need to make sure that possible advertizers might not be offended. Or there might be a gallerist or curator who decides which photographs will end up hanging on the walls of a gallery or museum. Or there might be a blogger making those kinds of decisions. And ultimately there even is everybody else - anybody who makes the decision to look at this newspaper or that magazine or website, to visit this gallery or that museum.

That aside, when someone writes that photography is cruel - what does that even mean? Given there usually is so much mediation going on, given there are so many hands in between that which was in front of the camera lens and ourselves - how can we talk about cruelty? And doesn’t cruelty usually involve someone making a decision? With a photograph being the result of someone pressing a little button on some sort of box made of metal or plastic, recording something that is in front of that box - how does the cruelty enter here?

Is it cruel to press the shutter button?

Is it cruel to show something that does exist?

Are we not complaining about the fact that someone dares to show us something that does exist? Something that we probably even knew about or heard about, something that, in any case, we didn’t do anything about, for whatever reason (because we didn’t want to or because we were unable to)?

Is not that the cruelty, that someone - the photographer - puts us into that place, the place that has us face something that we did not want to face?

Remember, here we’re talking about photography that makes us feel bad, not photography that makes us feel good (for whatever reason). When we say that photography is cruel, do we not say that photography itself lacks the mechanisms we have put in place to shield us from what is all around us, from all those unpleasant things?

Photographs don’t lie (unless photographers make them do it) because they can’t. Is that cruel?

I think it might just be. I think that is what people mean when they say that photography is cruel. That’s why it is always the messenger who gets blamed. It’s easier to blame the messenger - or to have some Sontagian debate about photography - than to face the fact that photography serves as a mirror: It doesn’t necessarily show us ourselves, but it does make us face the stories we have constructed for ourselves, the mechanisms we have adopted - whether because we simply have to (political correctness or the stuff our society wants to believe in) or because we want to (the stuff we want to believe in).

Because photographs enter the brain with such an immediacy, we have few defenses. Photography is cruelly effective: It hits us right where it hurts.

So we might as well cry out (“Ouw!”) - instead of pretending a disservice is done to us, instead of shooting the messenger. If it hurts why not let it hurt, why not allow it to hurt, why not let it puncture the thick shell we have constructed around ourselves?

Photography is not cruel. It just refuses to play by the rules of our game. It refuses to engage in the deceptions we are using so often to shield our eyes from the world’s cruelty.

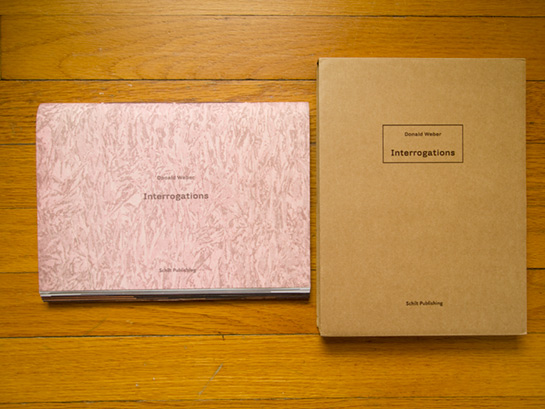

Interrogations, photographs by Donald Weber, essay by Larry Frolick, 160 pages, Schilt 2011