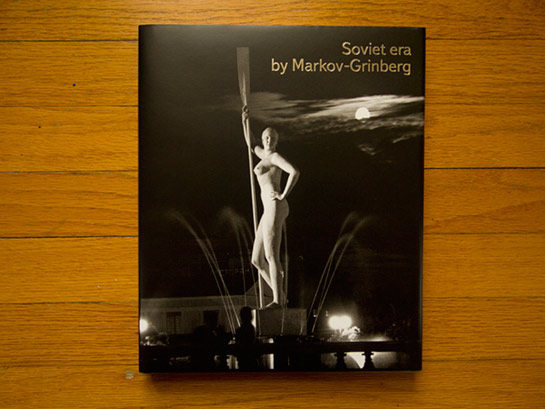

Review: Soviet Era by Mark Markov-Grinberg

I noticed how the popularity of my photobook reviews roughly scales with the popularity of the photographers. That’s bad news, of course, for a lot of photographers, whether they are up-and-coming talent, simply not very well known for whatever other reason or, and this is another factor, well-known somewhere other than the internet. There are two filter bubbles, the one where we seek out that which we already know (which then confirms our beliefs and thus makes us feel good about ourselves), and the one where a lot of stuff simply is not available online. Mark Markov-Grinberg might provide a good example - try to find information online, and you come back with not much - other than, maybe, the occasional image on The Retronaut (where photography is mostly used as some sort of nostalgic novelty item, so that we might be amused by the fact that we’re ignorant of the past). Luckily, Soviet Era now offers a chance to discover the photographer’s work. (more)

Amazingly enough, Markov-Grinberg was born ten years before the Soviet Union came into existence, and he lived long enough to see it fall, too. He ended up photographing a air bit of it, the early days of Stalinism, World War 2, and beyond. There is much in this book for us to learn, and this extends beyond that which is portrayed in its photographs. Of course, these photographs essentially show the official Soviet Union, (presumably) a land of happy workers. It’s easy to dismiss these photographs as propaganda, which inevitably, they are. But we’d be ill-advised to look at history Retronaut-style, ogling the weird to feel good about ourselves. History is useless unless we look at its reflection in our times. We might not live in the Soviet Union. But photography is photography, and it doesn’t take much to extrapolate (or even find) some of Markov-Grinberg’s conventions to (in) our world.

I had to think of that during the past Olympic Summer Games where a lot of photography essentially looked as if it had sprung out of Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia. This has got to tell us something. At the very least, it shows us photography’s uncanny ability to extrapolate things from the world that are shared across the ages, basic human emotions as well as our desires to be in awe of certain things. This doesn’t mean that what was propaganda then is propaganda now (even though in some cases it actually is). It does mean, however, that we can use photographs from the past to learn about what photography does - much like medical students learn to dissect corpses first before dealing with living beings.

Thus books like Soviet Era not only teach us about a certain artist who lived in a certain place at a certain time. They also teach us about photography as a whole. Properly applied, they can teach us about our times, about how what we see in photographs today often can already be found in photographs taken in a seemingly different world. This process is the opposite of nostalgia: Instead of looking (and thus longing) for that which was better in the past, we’d be looking for that which already existed in the past - so that we can learn about the present and, possibly, change the future.

Can a photographer who lived in a communist dictatorship in the 20th Century teach us something about us, who live in democracies in the early 21st Century? Yes, he can. We just have to look.

Soviet Era, photography by Mark Markov-Grinberg, introduction by Zhanna Vasilyeva, 160 pages, Damiani, 2012