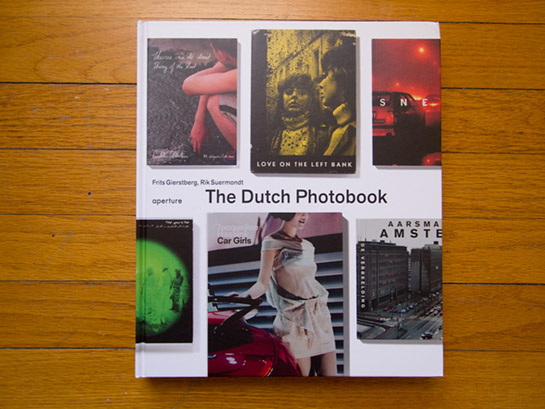

Review: The Dutch Photobook by Frits Gierstberg and Rik Suermondt (eds.)

In that ever (and rapidly) expanding industry of books devoted to photobooks, the one I had been really looking forward to was the one about Dutch photobooks. Ever since I discovered the amazing world of Dutch photobook making, I have been trying to make sure that that part of my own collection keeps growing as steadily (or maybe even more so) than the rest. So here it is now: The Dutch Photobook, edited by Frits Gierstberg and Rik Suermondt, with additional contributions by fourteen other authors. Now I don’t have to rummage through my book collection any longer to show people why I’m excited about Dutch photobooks. That’s a most welcome development. (more)

But joking aside, with all these books about photobooks that are centered on geography, for all kinds of reasons, some regions are just more interesting to look at than others. Japanese Photobooks of the 1960s and 70s is such an exciting book because during those roughly twenty years there simply was so much happening in Japanese photography, with a whole generation of new artists with very new ideas pushing into the scene. In more or less the same way, albeit for different reasons, Holland is a unique place for photobook making, and as The Dutch Photobook shows, it has been since 1945 (the book covers books made after World War II). To a large extent, this is because of the close collaboration between Dutch photographers and graphic designers (I think it also helps to realize that the general appreciation and support of the arts is vastly higher in Holland than in many other countries).

Good photobooks require having good photographs. But good photobooks need more than that. Photobooks, when done well, are not merely collections of photographs. They are pieces of art in their own right, which means that the contributions of the non-photographers are crucial. Dutch graphic designers have been pushing the medium photobook away from its often stale, conservative, or outright boring form that has been so common for so long in large parts of the world. I always recoil a little bit in horror (at least on the inside, on the outside I try to remain calm) when a photographer tells me they designed their own photobook. Make no mistake, some photographers are good designers. But most are not. There is a reason why you spend years and years learning about graphic design, just like how you spend years and years learning about photography. Being married to a graphic designer, I’ve learned that good design is an art form in itself: The simpler it looks, the trickier it actually is.

But it’s not just a question of cool design, it’s a question of cutting-edge photobook design. To design a photobook, you have to understand how it works, what it does, how the design might support the narrative. There seems to be no shortage of designers in Holland who know about this, and whose design elevates the photography, and the narrative, beyond what a carefully edited and sequenced selection of photographs might be. The Dutch Photobook is not primarily a book about photobook design. But it shows what happens when you have an environment where literally every aspect of photobook making comes together in a perfect mix.

The book is organized around six main subject matters or topics (The Dutch Landscape, Forever Young, Roads to Tomorrow, Wanderlust, The Magic of the City, and The Autonomous Photobook), with each chapter then following a simple chronology. This makes for an interesting way to look at the photobooks - the reader can compare books based on these subject matters, adding more depth to the survey than a mere chronology of books might provide. Each photobook comes with a brief text about it - essentially, in form The Dutch Photobook follows the Parr/Badger model. People interested in all kinds of information are being indulged with spreads of the book organized by publication date (useful), size (I’m not making this up), or edition size (for übergeeks).

I don’t know where this trend to make books about photobooks will take us - I heard there’s one about China in the making, plus there seems to be a Parr/Badger Vol. 3. I have the feeling that the appeal of purely geographical books might exhaust itself soon. That said, if you need just one book such geographical book, it clearly is The Dutch Photobook (OK, it’s two, you also need Japanese Photobooks of the 1960s and 70s).

Highly recommended.

The Dutch Photobook, editors: Frits Gierstberg and Rik Suermondt, various authors, 240 pages, Aperture, 2012