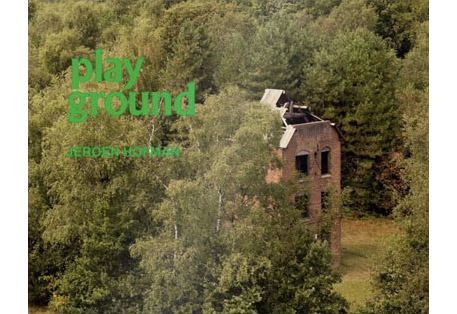

Review: Playground by Jeroen Hofman

Jeroen Hofman must feel like one of the luckiest photographers. Much like Gregory Crewdson, for Playground he got to photograph elaborately staged sets, with many actors, situations clearly out of this world and very much part of this world - and all he had to do was to point his camera (elevated high up on a crane). The staging, the production were taken care off by other people. Not for the purpose of the pictures, but still. You get firefighters scrambling to put out fires, people in hazmat suits looking for dubious substances, soldiers invading homes for whatever reason… It’s a different dystopia than Crewdson’s, the psychological suburban discomfort replaced with a much more threatening urbanized real violence. (more)

Of course, you could easily argue that it’s not the same thing at all. Crewdson’s world obviously is fake, constructed for the purpose of photography, constructed to present an artist’s view of our world. Hofman’s world isn’t really his world, it’s what he found after talking to authorities to get permission to photograph all those exercises.

In other words, Hofman’s world is very much real, it’s our frightening world. Crewdson’s world could be real, and we don’t want it to be our world. We can deny that Crewdson’s world exists, but we know that Hofman’s world is right around the corner, possibly encountering us at any moment.

One of the reasons why I am reminded of Gregory Crewdson so much is because there is a visual detachment in Playground. It works in a different way than in the American photographer’s work. There, the photographs have been digitally manipulated so much that things look almost artificial. The light simply doesn’t work that way. It’s a compelling fantasy whose problem is that it looks just too compelling. The psychological terror is brought to the surface, leaving nothing to the imagination (that’s not necessarily bad, clearly there’s an article for another day).

In Hofman’s world, the visual detachment for the most part works through the God-like view, elevated high up (Andreas Gursky has been playing with that trope quite a bit, to the point that things started to look pointless, as in his images of oceans). The world is turned into an insane diorama - where things are constantly under threats, where small figures somewhat helplessly (or so it seems) go about their futile business of mostly fixing things (the soldiers’ business obviously looks different).

A large-scale book with an incredibly attractive design (I don’t want to bring up Dutch book design again, but still…), Playground can be bought directly via the photographer’s website. It’s a very high-quality production, and anyone seriously interested in photobooks might want to order a copy before they’re sold out.

Playground, photographs by Jeroen Hofman, essays by Pieter van Vollenhoven and Rob de Wijk, 130 pages, self published, 2011