What Photographs Do And Cannot Do

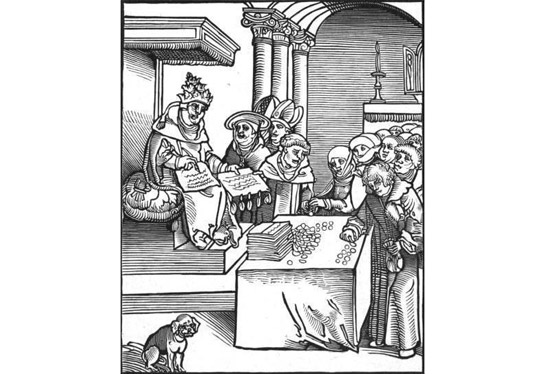

We are all sinners. Lest you wonder, I have not had a religious epiphany. However, organized religion can offer surprising insights into the human condition. For a while now, I have been fascinated by the Catholic concept of Indulgence, in particular by abuses in the Middle Ages: People were promised they could buy themselves out of all kinds of sins if they only paid enough money. It’s a bit of a stretch, but an entertaining exercise nonetheless, to ask to what extent looking at - and buying - photography in effect is a contemporary version of just that. (more)

Needless to say, I’m not talking about all of contemporary photography. I’m mostly interested in contemporary photography dealing with what we could call big issues, for example environmental pollution. A good recent example, in fact the example that had me thinking about this, is Pieter Hugo’s Permanent Error. Permanent Error is one of those photography projects that manages to contain not just one, but various things we should be very concerned about, including disastrous environmental practices, our wasteful society, us sending our junk abroad so other people have to deal with it, our total neglect of Africa and the many problems the continent is struggling with, etc. Another example would be Chris Jordan’s Running The Numbers.

We should be concerned about all of these issues, and the photographers deserve credit for making us face the results of the fact that for the most part we aren’t so concerned about them at all. Because, let’s face it, if we were more concerned about, say, our wasteful society we would do much more to reduce waste.

However, we are not completely unconcerned. Deep down, we do feel guilt, at least to some extent. One of the things we seem to be doing to deal with that guilt is to go to an exhibition of photography like Permanent Error or Running The Numbers, to look at photography that makes us face our, well, sins. If we have the money, we buy a print or at least a book.

Here’s the thing, though: Unless we change at least some of our behaviour after seeing these photographs, we’ve done little more than being engaged in a contemporary version of temporarily buying ourselves out of a sin. For the photographers to really have achieved their actual goals we would have to change our life style. Of course, this asks for a bit more than the simple act of looking at a photography exhibition or buying a book.

I have spent a lot of time thinking about the role of photography in this process. Photography is a curious thing: It has the power to confront us with the most gruesome events, yet it seems to have very little actual power to make us change our behaviour. I’ve argued elsewhere on this site that we can’t really blame photography for the fact that so little is changing: After all, photographs don’t make decisions, we make them. And we might decide not to do anything (which seems to be the most common decision).

But there seems to be a little more to this. I think we often take the process of looking at photographs as a replacement for doing something that could potentially help solve a problem depicted in them. It’s almost as if we think that if we look at a photograph of, say, waste and then feel bad about it, that’s enough to solve the problem. Clearly, it’s not.

A variant of this is provided each time a major newspaper decides to put a gruesome photograph on its front page. Here is a recent example, involving The New York Times. Am I the only one disturbed about how much media coverage was not about the actual problem, but about the fact that the photo was on the front page? (just as an aside, the amount of condescension contained in the executive editor’s phrase “Readers can follow more than one important story at a time” is absolutely mind blowing [follow the link for the context it was used in])

Photographs are not entirely powerless: They can make us feel bad (or good). But they cannot change the world. We can change the world. For that to happen, we must be open to what photographs tell us. Looking at photographs can be part of us changing the world. But only looking is never enough.

Illustration: Woodcut of the pope selling indulgences, from Passionary of the Christ and Antichrist by Lucas Cranach the Elder, source