Review: Photographs by Fred Herzog

Why would anyone walk around and take photographs in the streets of Vancouver? Here is Fred Herzog’s answer: “After about a year of shooting I increasingly felt, ‘somebody has to do this.’ Because otherwise people in the future would only be able to go to People magazine or Look or Time or Life or any of those to see how people looked at the time.” This is a remarkable statement, placing the photographer and his work into the documentary realm. What I most like about the statement is the photographer’s ambition, however. I personally don’t care so much whether I’m looking at street photography or documentary photography in Herzog’s images. What I do care about is the quality of the work and the ambition that shines through. (more)

There still is a lot of talk about a photographer’s intentions. You have some intentions, take a photograph, and somehow the photograph then communicates those intentions. A different take on this idea is that the meaning of the photograph needs to take those intentions into account (it typically is never explained how we actually know about the intentions when the photographer is unable to tell us directly).

It’s probably pretty obvious from how I am describing this situation that I have some problems with the whole intentions idea. Ambition, however - now that’s a different topic. Needless to say, ambition probably is as problematic a topic as intentions - how can we know them? But intentions are necessary for the meaning of photographs, whereas ambition is not. You can argue about intentions, but it’s much harder to argue about ambition. Ambition you have to accept. Somebody has to do this.

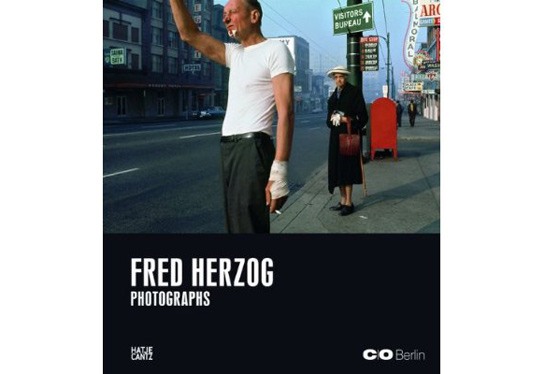

So here we have Fred Herzog: Photographs, a collection of images taken over the course of many decades. The book arose out of an exhibition at Berlin’s C/O gallery, and it features an introduction to the work plus an interview with the artist (from which the quote used earlier was taken).

I suppose I could (should?) now make all kinds of comparisons with other colour photography, either from the same period (for example Saul Leiter: Early Color) or from around the time when colour photography “officially” took off in the fine-art world (you know the story). Not that there’s anything wrong with such comparisons per se, but I often think that before filing a body of work somewhere one needs to take it for what it is first.

It is true, I do see echoes of, let’s say, Walker Evans in some of Herzog’s photographs (the photographer acknowledges his debt to Evans in the interview). But I also see a lot of Fred Herzog in these photographs, which, I must add, requires a bit of work, because you actually have to look past the colour and nostalgia and inevitable references. In many of these photographs, the combination of colour and composition is sublimely beautiful, especially where the “street” aspect is less pronounced. It’s quite amazing actually.

I don’t know whether seeing Fred Herzog’s Vancouver necessarily adds anything to the Vancouver we might see in old magazines. But I do know that seeing Fred Herzog’s photographs adds something to the canon of photography: a collection of images centered less on a particular city at a particular moment than on the world we live in, and the things we do.

Recommended.

Fred Herzog: Photographs, photographs by Fred Herzog, essays by Felix Hoffmann and Claudia Gochmann, interview with the photographer by Stephen Waddell, 192 pages, Hatje Cantz, 2011