Review: Shelter by Henk Wildshut

Our sheltered and rather comfortable Western life styles come at a price: We are stressed, overworked and - except for the lucky few - underpaid. And now we also have to worry about all those illegal immigrants who want to come and take our jobs. OK, I am not worried about that, but in this society a great many people are. In fact, people are so worried that they built a fence, hundreds of miles of it, along the Mexican border. Everybody is welcome to admire us for our freedoms and our life style, but please do not come and try to join us. (more)

There is a somewhat different way to think about this: The people who pay the price for our life style are the people who want to enjoy the same life style, but who can’t, who are looking at the other side of the fence. Economically, this even makes a certain amount of sense, at least on a very superficial level. Politics these days doesn’t go any further, so we might as well play this game: If we allowed everybody to come here, there’d be too many people for too few jobs etc. Here’s the thing, whether this is in fact true is an entirely different matter (I don’t think it is, but that’s for another day).

But what we are essentially doing is to tell other people they can’t come because, sorry, there isn’t enough cake to cover us and the newcomers. We don’t want to share. Other people have to remain in poverty so that our life style is not threatened. That is why we’re building the fence.

Focusing on the fence at the Mexican border is somewhat unfair, though. It’s not as if Europeans didn’t act out the very same theater. As far as I know, there are no fences, yet, even though I’m pretty sure that’s just a lack of knowledge on my part. But illegal immigration is a red-hot topic in Europe as well, with the same kinds of dynamics playing out.

These days, it’s particularly sad to watch the situation in Europe, as there is a lot of wailing and gnashing of the teeth about all the refuges the civil war in Libya has been causing: “A £500 million accord, signed between the EU and Tripoli last year, has helped combat the flow of illegal immigrants in recent months.” reports a British newspaper. Seen in this light, the eagerness of some European countries to intervene suddenly doesn’t look so altruistic any longer: Instability causes migration. Migration causes illegal immigration, because of course people would rather live somewhere where there are peace and jobs.

Henk Wildschut’s Shelter looks at the situations of illegal immigrants who have made it into the EU. Typically, most immigrants don’t just want to live just anywhere, they have particular destination countries. For those aiming for Britain, the fact that it’s an island makes things very complicated. So illegal immigrants are forced to live in self-made shelters while trying to find ways to get to Britain. In fact, all across the EU illegal immigrants are living in such shelters. Writes Wildschut “I did not expect seeing something this ‘un-European’ less than 250 km away from my house.” Probably most people will be very surprised to learn about the living conditions of these illegal immigrants in the middle of Europe.

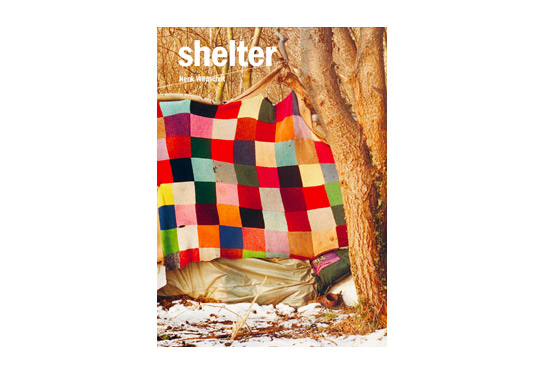

Shelter thus focuses on just that: Photographs of these self-made constructions, designed to house someone living as an illegal immigrant in Europe. For the most part, their inhabitants remain invisible - except for the occasional image of a few of them. Of course, they can’t risk being photographed. But those shelters, often little more than a few major branches plus some cardboard or old blankets, provide the visual cue: This is the price some people are paying, in fact willing to pay, so that we (Europeans in this case) can enjoy our cushy life styles.

A superficial reading of these images might possibly decry seeing too much of a concept here, but the photography succeeds exactly because it does not show us everything we might think we need to see. And just like there are no faces in debates about illegal immigration, there are none here, making us confront a bit of the cruelty that lingers just underneath the surface of those debates.

Shelter, photography and text by Henk Wildschut, 112 pages, Post Editions, 2011