Ping Pong with Michael Itkoff, Round 5

Round five of the ping-pong chats with Michael Itkoff centers on whether/how we can understand art/photography produced in different cultures. (more)

Michael Itkoff: Hi Joerg, I’ve just returned from a government sponsored photo tour of a few cities in eastern China and thought it might be an interesting catalyst for discussion.

On the trip, which toggled frequently between the amazing and the absurd, 100 Chinese photographers and six Americans were bussed around Daqing, Harbin, Tangshan, and Beijing. In addition to countless highway rest stops our group visited museums, oil fields, wetlands, monuments, shipping ports, Mongolian villages, markets and more. See if you can find me in the shot below (sort of like Where’s Waldo…).

This article in the NY Times recounts a recent trip for journalists through Tibet. It aptly describes the difficulty of getting any real sense of a place while under constant supervision. Our handlers were relatively easy going; as long as we stayed with the group, our photographs were not vetted and we were given the freedom to shoot what we wanted, how we wanted. As soon as we broke away, however, the local police quickly moved in to ask questions and make sure we were legitimate, accredited photographers. Throughout the trip, my central concern was to maintain my integrity while being asked to ostensibly produce propaganda images for the government of China.

The police chief of Daqing, an avid photographer himself, happily escorted our bus from place to place, lights flashing and sirens blaring. At one point a rainbow appeared in the Wudalianchi Geopark and the photographers dashed onto the bus in order to find a better vantage point. Imagine, if you will, a busload of clamoring cameramen struggling to shoot a rainbow out of a moving tour bus. We would find a likely spot, scramble out and disperse in the rocky landscape for a couple of minutes. Soon Chief would yell (in Chinese, naturally) for everyone to get back on the bus to look for another spot.

Wandering away from the group for a moment, I marvelled at the joy with which these shooters made images. With one eye in the viewfinder, the photographers chatted from picture to picture happy-snapping their way through the world. Well, I thought, this isn’t so bad. And, really, it reminded me of when I first began making pictures, when the whole world begged to be photographed and I saw pictures everywhere I went. Watching these photographers I wondered: have I lost that joy? Have I become too jaded to look lightly at the land?

Although there are many amazing artists making work in China, the Chinese photographic industry remains in its infancy. Photo China, a publication sponsored by the government, was one of the main sponsors of our tour. Vision Magazine leans a bit more towards the fashion and pop-culture world. FotoFest’s 2008 focus on China was notable in its effort to highlight the work of photographers in China but I am not familiar with others that have such scope. In a country where information control is a key issue, the political implications of image making is clear. In the next few years I imagine we will be seeing more, and better, work coming out of China than ever before.

Jörg Colberg: When I was in High School, we did a trip to East Germany, which was then a separate country - a Communist dictatorship. Everything was quite a bit less flashy than I imagine your trip was like, but from what I can see the similarities are quite striking actually.

I personally don’t find it very interesting to try to figure out how we are going to deal with the propaganda aspect. What I find more interesting is how we can learn - or at least deal with - the (possible) clues that Chinese photographers might put into their work to show dissent (if we want to call it that). In fact, that’s not even just a question of dealing with photography from China, you could easily apply it to, for example, Nobuyoshi Araki’s photography, a lot of which contains elements that make a different kind of sense if you know the cultural background they’re created in.

How can we get there? How can we become more aware of what we’re dealing with? I think our Western debates are amazingly one-sided and often knuckleheaded when it comes to trying to understand photography produced in cultures which are very different from our own. We might all be using the same iPod, but we probably disagree about a lot of other things. Just an example: When people say that Europeans love the American way of life because they eat at McDonald’s and go to see Hollywood movies, that totally misses that for example neither the Germans nor the French would even consider giving up their four weeks of paid vacation and affordable universal health care for what we have in the US. And these are countries that - at least superficially - look completely like our own!

So how do we even deal with what we’re seeing from artists in China?

MI: You raise an interesting point about the difficulty of understanding photographic images without having a true sense of the culture that produced it. In my mind, interpreting images remains remarkably dependent upon context whether they were produced half a world away or within the same city. Often the challenge for image makers is to include clues, symbols, semiotic references that will provide for a semblance of perspective and, therefore, intent.

For me, Araki’s work consists not so much of expressions of dissent but more about the airing of deeper, psychological impulses that seem to be shared throughout Japanese culture. In my humble understanding, under the veneer of conformity and restraint lies a tremendous hunger for exotic/extreme eroticism and entertainment. Of course, Araki deals with a number of subjects but his continued interest in young women and bondage, coupled with his cultivated persona, seems more focused around taboo and celebrity. The body is a subject of universal, cross-cultural understanding and although there is rich political potential in using the body as a foil Araki’s intent is more mundane.

Expressions of dissent in Israeli culture are few and far between. The editorials in Haaretz, Israel’s largest newspaper, show a surprisingly diverse cross-section of opinion but to have a soldier speak up in protest is especially potent. I recently found out about the group Breaking the Silence which gathers images and testimony from former soldiers in the Israeli Defense Forces. The images are shown in a touring exhibition and some of the former soldiers give presentations about their experiences. I saw a Breaking the Silence lecture at NYU which was truly evocative and we have begun putting together a multimedia podcast with the work.

Photography, and art in general, attempts to communicate one’s unique subjectivity to another but its never easy to understand another person, let alone an entire culture. If the images serve as more than illustrative expressions of China’s grandeur there will be tension expressed through composition, juxtaposition, or by simply showing a China that is less than ideal.

At this point it might be interesting to see some examples of work (by Chinese photographers or otherwise) that belie or frustrate attempts to interpret them. Do any come to mind?

JC: I don’t think it’s quite as simple as that. Your interpretation will always be based on your own assumptions and cultural background. So you can try to look at photography from, say, China and try to figure out which bits might belie or frustrate your own attempt to interpret them, but that’s using your own perspective - and your own perspective could be vastly different from the one of the artist.

Of course, you could argue that that’s always the case, that people always have different backgrounds. To a degree, that’s certainly true. But I don’t think it’s just a matter of difference in degree.

Here’s an example. The other day, I read about Chinese comic (“graphic novel” - who are we trying to kid?) artists who use extreme amounts of kitsch to get around censorship (I only have a German link). If you didn’t know about this, you might draw very different conclusions about the kitschiness of the comics: A kitschy, very happy world - that could literally be such a world (the “grandeur” you were speaking of above), or it could be a subversive commentary about a world that tries to look that way, but that isn’t. So it all seems rather more complicated than one would imagine. I don’t think it’s so simple to spot it, even when we’re only dealing with comics.

A few years ago, I went to see a show of Chinese photography at London’s V&A, and I remember how reading the descriptions/explanations really changed the ways I viewed the art works. The descriptions did not explain each and every aspect of what I was seeing, but they introduced some of the cultural differences I wasn’t even aware of - I literally looked at the photographs with different eyes afterwards.

Speaking of “examples of work (by Chinese photographers or otherwise) that belie or frustrate attempts to interpret them” - don’t all good pieces of art do just that, regardless of where they’re made?

MI: Well, I don’t believe that the frustration of interpretation is the measure of “good”ness in art but a measure of ambiguity may be a crucial factor. In our earlier discussions we agreed on the qualification that a good photograph would move the viewer in some way. It would influence, by some small degree, the way in which the viewer felt about the world. That conversation came about after discussing degrees of explicitness in art and I still feel like a piece of art that takes me on a journey, forcing me to think, to feel, to understand the intent of the artist is more successful than one that lays all of its elements clearly on the table. And, so it appears we agree, it is within the struggle to interpret a photograph or work of art that one experiences a sense of revelatory complicity or true understanding.

The captions in magazines and museums are critical in providing contextual clues but I have become interested lately in attempts to free images from text and allow them to speak for themselves. Graphic novels like Owly or artists like Hans-Peter Feldmann and Sarah Charlesworth come to mind here.

I enjoyed looking at the examples of contemporary Chinese graphic novels in the Spiegel article. Employing an aesthetic that is as obvious and dismissible as kitsch can be a sophisticated way to inject subversive elements into what might otherwise be considered benign. For years, Otaku culture in Japan has successfully employed the outlet of fantasy to air all manner of thoughts that might normally be considered taboo or subversive. Graphic novels and art, even some video games, provide a place in which societal mores can be questioned and challenged, where interpretations aren’t (necessarily) fixed. I think this alone is a big reason that I enjoy them…

The graphic novel is a great example of a medium that both shows and withholds at the same time. By weaving in the character’s dialogue, a back story or context is created that underlies the storyboard’s unfolding narrative. While it is certainly possible to grasp the meaning of events as they unfold in foreign graphic novels, much of the subtlety and richness of the story-line is lost without the explanatory dialogue or narration. In either case, the graphic novel seems to rely on a high-degree of explicitness (ie. Palestine or The Boys) unless the storyline itself revolves around something nebulous (ie. the dream world in Sandman).

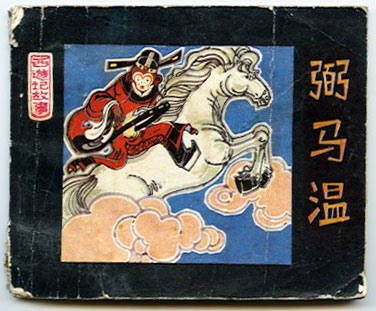

I picked up a few interesting mini-comics while in China.

One tells the story of the mischievous Monkey King and another consists of stills from a Cultural Revolution era propaganda film [see top image].

Although I am not familiar with the specific scenario happening on the cover of the propaganda comic, the intensity and gestures of the crowd provide enough clues to help me begin to make an interpretation…

JC: Well, that’s propaganda, and even though there might be some nuances there that we might miss, that’s a very different game than dealing with non-state sponsored Chinese artists. But while I’m usually not that interested in propaganda imagery there’s one thing that does interest me, namely why propaganda fascinates so many people. There are scores of books about Russian or Chinese propaganda posters, and it can’t be the sheer camp that makes these posters or, in your case, comic, so interesting.

But I feel we’ve been talking past each other here, even though we’re ultimately interested in the same thing. We do seem to agree that we’re interested in art that takes us on a journey, as you phrase it. The difference between us is that I don’t think you can go on a journey with a piece of art whose cultural background is completely alien to you. Or maybe more accurately, you can’t go on the same journey as those people who know about the cultural background. And that’s problematic for me, especially when we look at art from places like China. We might be very good at spotting propaganda, but whether we’re equally good at spotting signs of artistic rebellion (or whatever else) I doubt.

Even with Japanese art or photography things can be tricky. The other day, a group of photographers and I discussed a photo by Araki, which showed a woman in a kimono eating some piece of watermelon or so. There also is watermelon on the ground. If I remember this correctly, at some stage, one of the students, whose mother is Japanese, said that watermelons are very expensive in Japan, so their use in this photo went beyond that which seemed so obvious to us.

MI: I have collected propaganda from my travels through Vietnam and China (along with the requisite souvenir bottles of liquor) because I am fascinated with the unabashedly direct aesthetics of state polemic. Since these relics represent a failed ideal in such a frothingly earnest manner they do carry an element of ironic camp but my interest lies in their role as objects of manipulation.

In today’s world, a typical ad comes through a number of channels: typically a private company hires an agency who produces and distributes a fine-tuned cross-platform campaign targeted at a certain demographic. Generally speaking, the ad will strive to create a feeling of distinction, difference, even exclusionary preference that comes with the use of the advertised product. Of course, we want to identify with the sexy models but it is an association born of our desire to transcend the nameless masses around us. Or our neighbor.

With state propaganda it is the juggernaut of the leading party that is itself creating and distributing a cruder message designed to unite a mass population around a simple idea. Something about this simplicity makes it seem like a cultural lexicon, a semiotic codebook, that I enjoy perusing. Plus it is hard to misunderstand propaganda (in any language) and there is something appealing about this bluntness. I’ll end this digression with two references: Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s Painting Photography and FiIm playfully diagrams some of the interactions between type, graphics and photography and the film Art & Copy provides an interesting look at the early days of the advertising industry. Fun fact: there are over 450,000 billboards (and growing) in the United States alone.

Certainly I agree with you that it is more difficult to go on the “same journey” of understanding as a foreign artist, or those that share the artists cultural background, when looking at a piece of art from abroad. Undoubtedly, as is often the case with personal expression, nuance and subtleties will be lost in translation. Of course, art has not made explicit its goal to share the same message with every person as most mass communication (especially propaganda) has. There is something to be said for the importance of the viewer in creating meaning and for the validity of any interpretation, whether it is informed or not.

Although I am not familiar with the Araki image of the woman eating a watermelon I believe I would have interpreted it thusly: A pretty young woman in a silk kimono is squatting in an urban setting and eating a watermelon. The color of the lush fruit and delicately flushed skin is undoubtedly sexual (as melons and flesh usually are) and that, coupled with the gesture of eating off of the ground would bring to my mind the woman’s animality, corporeality, and mortality. In addition to the rendering of fruity pulp, there is a shade of implied violence at work here, as entropy on flesh. The girl and melon both will lose their radiant luster and fade, pale and still, into the background. The burst melon shows us the results of aggressively fulfilled desire, revealing what is underneath the surface and acting in tension with the still-whole silk and skin of the lovely woman.

Admittedly I would not have recognized that the melon is a rare and expensive treat in Japan (bringing up socio-economic issues of class and etc) but my knowledge of Araki’s work and shallow understanding of Japanese culture would be enough for this attempted, and overwrought, interpretation.

Here is another example:

Need we know that this action, performed and documented by the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, consists of the dropping, specifically, of an ancient Han dynasty urn? No, I would answer, but it helps. The destructive act itself, along with the confrontational stance of the figure in the picture, provides enough clues that this is an act of rebellion with potential political import. The context, in this case and in the case of the watermelon, will enrich my understanding but will not completely change it.

I have always argued for the importance of context in correctly understanding and interpreting images, and this includes an artists cultural background, but I would also argue in favor of the attempt to understand and the struggle to interpret as valid activities in and of themselves. A decontextualized photograph can mean many different things to many different people but as long as they strive to undertake the “journey” of understanding I will be satisfied. Today’s contemporary art, and visual culture in general, is rarely as straightforward as propaganda with its simple graphic cues. At all times an active engagement with the medium at hand, along with a critical sensibility, is necessary to navigate our visual landscape.