Review: Terezin by Daniel Blaufuks

“The first image I saw of the Terezin camp, formerly known as Theresienstadt, an hour’s drive away from Prague, was in a book by the German author W.G. Sebald.” This first sentence in Daniel Blaufuks’ Terezin sets the tone for what is to follow, in more ways than just one. If you are familiar with Sebald’s work, you realize that the book in question is Austerlitz, and you will also remember that author’s use of photographs and other images. The photograph in question (“It portrays a space that seems to be an office.” - D.B.) set off a process in Blaufuks’ mind, which had him research Terezin. (more)

The reality of Terezin was simple and brutal: It essentially was a transit camp from where people were sent to their deaths in Auschwitz. In an essay at the end of Terezin, Karel Margry writes

In all, between 1941 and 1945, 141.000 Jews were sent to Theresienstadt; 33.430 died there; and 88.000 were shipped to death camps in the east (of which only 3.500 survived).As Blaufuks worked on trying to understand the reality of Terezin, by looking at documents, postcards, photographs, and diaries, he came across a movie made about the camp, produced in 1944/45. In 1943, the Nazis tried to round up Danish Jews - they managed catch 450 - and the Danish government demanded to be able to visit them. Adolf Eichmann, organiser of the deportation of the European Jews, agreed to such a visit, in the Spring of 1944. In order to make the camp presentable, it was given a complete make-over, which took many months. Margry:

To make the ghetto less crowded, 7.500 people were shipped off to Auschwitz.The Red Cross inspected Terezin in June 1944 and did not find any problems. Margry again:

As a direct result of the visit, the International Red Cross declined to visit other camps to the east, notably the ‘labour camp’ at Auschwitz.A few weeks after the Red Cross visit, the Nazis made a movie about Terezin, as additional “proof” that all was fine, with the Jewish prisoners made to act. The second half of Terezin deals with Blaufuks trying to come to terms with it:

The memory of this room prompted me, for some reason, to find the film fragments and to try to retrieve the images from their intended purpose, from the carefully constructed reality the film was planned to create for posterity. […] To understand how images can still lie even when we think we know the truth about them.This is where his writing stops, and where there are only movie stills, many of them overlaid with what Blaufuks calls “the colour of memory”, and photographs from Terezin.

The effect is stunning.

Seeing the second half of the book reminded me of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s dictum:

Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

Beyond its exploration of the camp, Terezin (the book comes with a DVD, which allows the viewer to see Blaufuks’s slowed down version of the Nazi propaganda movie) is a mediation on images, their use and power, moving in what you could call a Sebaldian space. Highly recommended (as are Sebald’s novels, btw).

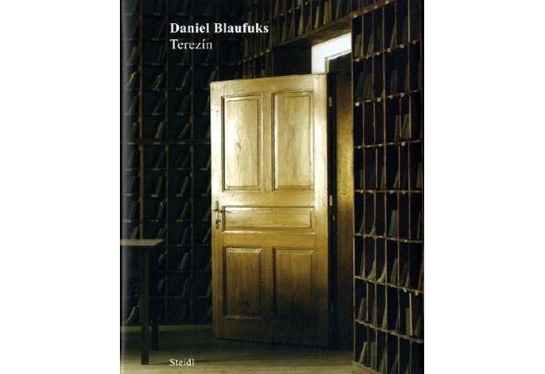

Terezin, photography, images, documents, etc. collected by Daniel Blaufuks, with an essay by Karel Margry, includes DVD, 192 pages, Steidl, 2010