Review: Schön War’s by Stefan Hunstein

At the end of World War II, large parts of Germany, especially the cities, lay in ruins. It was mostly due to what Germans call the Wirtschaftswunder (“economic miracle”) that in surprisingly little time in the West everything was back to normal - or maybe more accurately to a new normal. Cities got rebuild, as did factories. While East Germany ended up being stuck in yet another dictatorship, this one Communist, for forty more years, West Germany developed into a stable democracy. Along with the Wirtschaftswunder came the happy and carefree days of the 1950s, which, as it turns out, were pretty similar to the Eisenhower years in the US. As long as you didn’t ask any questions, you were golden, and who wanted to ask questions anyway, what with the Communist menace next door. (more)

Needless to say, there was a dark side, many aspects of which are emerging only now - lots of old Nazis in cushy positions, a denial of the role the Wehrmacht had played in Hitler’s war, etc. You can even trace things in areas such as German literature, where right after the war, authors wrote about the war, including the destruction of German cities. Most of those books ended up being forgotten, so that for example when W.G. Sebald asked why German authors had not written about the bombing of their cities, it turned out he had asked the wrong question. There were many books, but in the happy and carefree West German world of the 1950s, nobody wanted to read them (for example, it takes a very strong stomach to read Gert Ledig’s The Stalin Front or Payback).

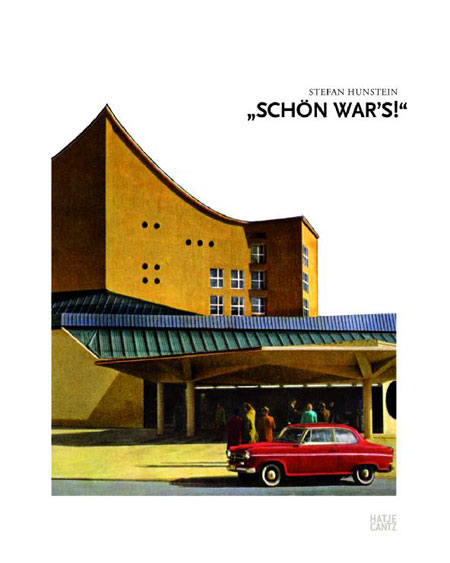

This is the background against which Stefan Hunstein’s Schön War’s needs to be seen. “Schön war’s” means “it was beautiful,” and the book shows scenes from old German postcards that the artist digitally manipulated. It is hard to tell what he did in each of the various cases, beyond the obvious garish colours he added. Some images, the essay notes, were cropped or altered in other ways.

You realize that things are a bit tongue in cheek from the fact that some of the colours are just a bit too garish, and other images are only partly colourized. And while the many locations certainly are preferable to bombed out ruins, the architecture for the most part is positively hideous, displaying a version of modernity that is entirely soulless.

Needless to say, with everything from the past now being reissued - whole forests must have got cut down for all the various Taschen collections of stuff from the 1950s, 60s, etc. (wouldn’t it be preferable to simply mark the trees as remaindered and leave them standing?) - it is tempting to view Schön War’s as yet another such book. I don’t think it is. Instead, it portrays an idealized, idyllic world - postcard views with the kitsch setting cranked up to 11, and it asks us to imagine ourselves in such a world.

Schön War’s, photography by Stefan Hunstein, essay by Petra Giloy-Hirtz (German/English), 152 pages, Hatje Cantz, 2010

PS: The German alphabet has more characters than the English one. There are three umlauts that look like an “a”, “o”, or “u” with a couple of funny dots on top (ä, ö, ü), and there’s something that looks like a Greek “beta” (but which in fact is a version of an “s”). There are two proper ways to write the umlauts, namely first, to write them with the dots, such as “ouml;”, or, second, to omit the dots but add an “e” at the end, so you’d get “oe” for “ö.” The latter is often simpler if you are using a non-German keyboard (after all these years, I still don’t know the combination of characters to tickle an “ö” out of my OS). Simply omitting the dots and pretending it’s the same character you cannot do, it’s like omitting the bar on the top of “T” to write “I”. A “T” is no “I”, just like an “ö” is no “o.” Writing “schon” instead of “schön” changes the pronunciation and meaning of the word: “schon” means “already”, and “schön” means “beautiful.”