When does similar become too similar?

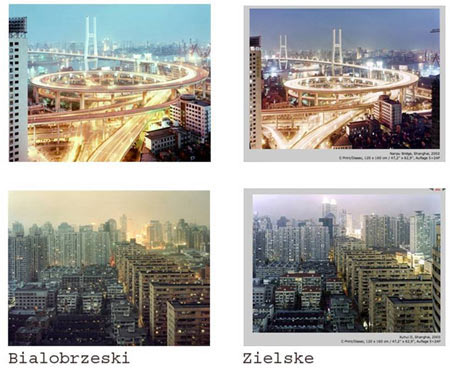

If you have been following this blog for a while you will remember this mosaic from one of my earlier posts, where I tried to tackle the problem of plagiarism. How can one decide when to cry foul? What is a good way to approach this complex? I’m not sure I have a better answer now than three and half years ago, but I’ve thought about it more; and it’s worthwhile to come back to this topic.

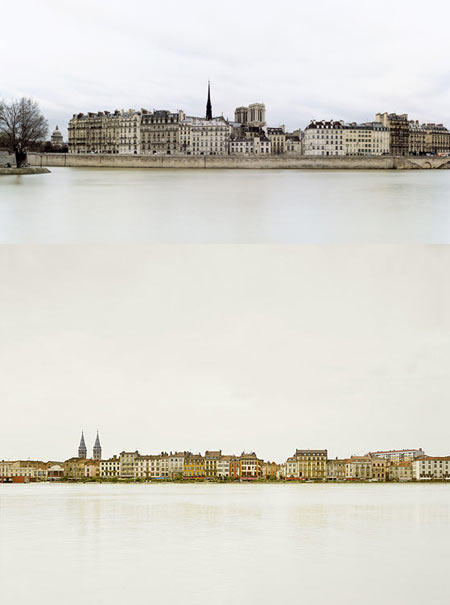

I started thinking about this again when I saw a post on Tim Atherton’s blog about David Burdeny’s Sacred & Secular, large parts of which look just like Sze Tsung Leong’s Horizons, and, as Tim notes, the work is also very similar to a lot of Elger Esser’s work:

That’s an image by Sze Tsung Leong on the top and one by David Burdeny at the bottom. Another recent case involved photographers Simon Roberts and - again! - Peter Bialobrzeski, where some of Roberts’ photos (from We English) look just like some of Bialobrzeski’s (from Heimat):

That’s an image by Sze Tsung Leong on the top and one by David Burdeny at the bottom. Another recent case involved photographers Simon Roberts and - again! - Peter Bialobrzeski, where some of Roberts’ photos (from We English) look just like some of Bialobrzeski’s (from Heimat):

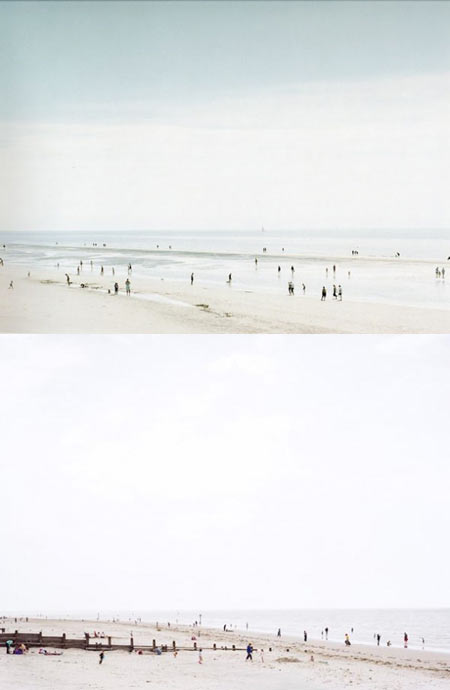

Here, it’s Bialobrzeski’s photo on top, Roberts’ at the bottom (and this page has more).

Here, it’s Bialobrzeski’s photo on top, Roberts’ at the bottom (and this page has more).

But, of course, not all cases look so obvious. What about Steven Meisel’s Dogging versus Kohei Yushiyuki’s The Park? Same aesthetic (we can safely ignore Meisel’s use of colour), same idea, but they look a bit different.

An obvious solution to all of this would be to say that whoever took the image first simply got ripped off by the other artist (which for these examples would mean that Peter Bialobrzeski had that happen to him twice!). But, of course, the obvious solution is not necessarily the best solution. In the interest of looking at the various aspects I can think of, let’s simply assume we only have one case to consider, involving photographers X and Y, with X’s photos being older than Y’s.

If we know for a fact that Y looked at X’s photographs and then decided “I’m going to take the same photos” we’d be all set. Case closed. Plagiarism. Of course, there pretty much never are such cases (even though as my earlier post shows, one can get awfully close). In fact, I’m always a bit surprised when people are very certain that they’re dealing with plagiarism. How do they know that Y knew of X’s work and then decided to copy them? Isn’t it possible that Y did not know of X’s work? Of course, one could ask Y about it, but then we’d simply change the problem: Do we believe her/him or not?

There’s got to be a better way to think about this. In particular, if we want to find a way to deal with this, there are two things we need to take care of: First, we have to make sure that artists’ works are safe from being plagiarized. But second, we also have to make sure that artists don’t have to worry about accused of ripping someone else off when in fact they are producing a meaningful variant of that other work.

Let’s start thinking about what we are actually dealing with by doing it the other way around. Instead of using two completed bodies of work, let’s start with one. Photographers sometimes ask me whether they can work on something that someone else has already covered. My answer is always the same: Yes, they can. What I am interested in, of course, is not to see an exact copy of whatever that first body of work is, but a variant.

For example, I know what the Bechers’ Cooling Towers look like. If someone produced a copy of that, it would be plagiarism - and not interesting: Why would I look at an exact copy that tells me nothing new when I can look at the original?

Now imagine someone decided to shoot Cooling Towers and added something entirely new to it, a completely different idea, approach, … Wouldn’t that be really interesting? And if that artist brought something different to the table, we could expect the work to have a different meaning, offering different facets maybe - or even contradicting the older work. Who knows? Being too strict with what an artist can do - “no, you can’t do cooling towers, because the Bechers already got that covered” - would clearly limit artistic possibilities.

I think this approach might offer some advantages when approaching the complex of plagiarism or of photographs that look very similar. Instead of looking at only the photographs and at how similar they are, why not look at what the two bodies of work do, how they approach the subject matter?

A consequence of this approach is that a body of work could be a rip-off of some other body if work if it was merely repeating something (even if the images themselves were very slightly different). Another consequence is that a body of work could be very different, if, while containing a few images that are almost the same as some found elsewhere, it had a very unique message.

And to make matters even more confusing two bodies of work that look very similar could still be fully acceptable if they met certain conditions - we’d really be talking about artistic merit here.

So the way I started to approach this topic is to see whether there are two distinct artists with unique artistic visions, or whether there is one plus a copycat one. Needless to say, this does not make the decision whether or not there is a case of plagiarism all that much easier. Maybe it makes it even harder.

But I think it opens new possibilities, and it moves the debate from such ugly territory as “rip off” or “someone is lying” to “what does this actually say?”. Such an approach seems especially important in a day and age where we get to see a lot of photography from all over the world - often very similar ideas, with the artists having no idea that someone else was/is working on the same thing.

On top of all of this, debates about plagiarism often end up in front of a judge - and judges aren’t necessarily the best people to talk about art. No offense if any judges are reading this, but judges deal with the law, whereas what we’re really talking about here is a question of art. Of course, there is a reason why copyright law is a bit vague when it talks about “fair use”: Trying to exactly define when and how to allow fair use would easily overwhelm law makers, and it would leave more problems than it solved. “Fair use” is not a rule set in stone, it’s a societal construct that we can talk about. And if people can’t agree on a case of “fair use”, an arbiter - a judge- has to step in.

Needless to say, in a commercial context, people might be less inclined to have debates about art - and in a commercial context, photography is dealt with differently anyway. So if any commercial and/or editorial people are reading this, please don’t give me any grief about my approach: I’m mostly interested in the fine-art cases.

So what about the examples on the top then? Are they too similar or not? Well, you be the judge now.

And, as always, I’m curious to learn about your ideas - send me a note, and I’ll be happy to add links, examples, opinions, quotes, … to this post.