An Interview with Ute and Werner Mahler

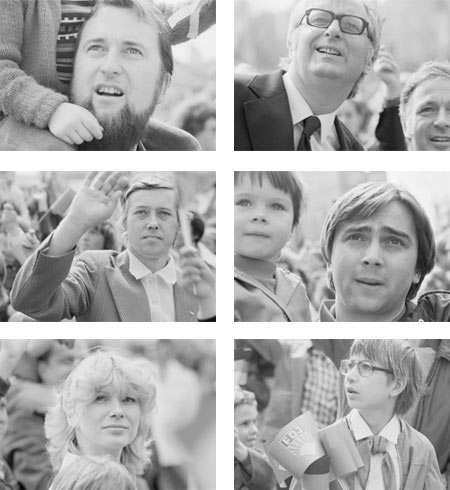

(© Ute Mahler/Ostkreuz)

(© Ute Mahler/Ostkreuz)

Twenty years ago, the Berlin Wall fell - an event for which there has been no shortage of coverage. The fall of the Wall also effectively meant an end for the GDR (East Germany), which soon would re-unite with West Germany to form today’s Germany. Berlin’s city magazine Zitty used the occasion to speak with Ute and Werner Mahler, two photographers who had lived and worked in East Germany, and who co-founded the photography agency Ostkreuz in the early 1990s. Photography from four East German Ostkreuz members has recently been published in Ostzeit.

When I read the interview I thought it would be of interest for more people than just the Germans. In the interview, Ute and Werner talk about life as photographers in East Germany, and what photography meant for them - and their audience. However, there was no English version of the interview, so I approached Ostkreuz and Zitty and asked whether I could translate the interview and re-publish it here. My thanks to everybody who made this possible, in particular to Ute and Werner, but also to Ostkreuz’s Jörg Brüggemann, Andrea Schewe, Christoph Wilde, and Zitty’s Daniel Boese and Claudia Wahjudi. The original piece, an interview by Daniel Boese and Claudia Wahjudi with Ute and Werner Mahler, was published in Berlin’s city magazine Zitty, 23/2009.

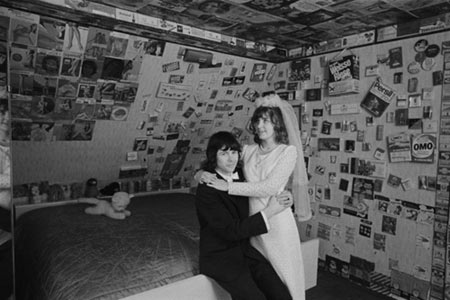

(© Werner Mahler/Ostkreuz)

(© Werner Mahler/Ostkreuz)

Your book “Ostzeit” was published at the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. But it shows only few photos from November 9th. Why is that?

Ute Mahler: You know those photos. Every year, in November, they are being published again and again. But long told stories are less well known.

For this book, you re-edited photos after 20, 30 years. What was your motivation for doing that?

Werner Mahler: It was our idea to tell stories, those stories that we experienced and photographed. For us it wasn’t important to shine a light on the big celebration, re-unification or big luck that happened to us - I’m not being ironic here, I’m serious. We wanted to show people what the GDR [East Germany] looked like, because we thought that over the past few years life in the GDR has been transfigured a lot.

Ute Mahler: And it has been condemned. There are really only those two extrema: Transfiguration and Condemnation. So we tried to show a wider view. Of course, there is a focus on private life, but that’s always the case when you deal with photography from East Germany - just have a look at the well known, important East German photographers. Almost all of them took a lot of photos of private life. Public life often was inaccessible for us.

Who are you thinking of?

Ute Mahler: Arno Fischer, Helga Paris, Evelyn Richter, …

Werner Mahler: …and Leipzig photographer Christiane Eisler, who took photos of punks.

(© Ute Mahler/Ostkreuz)

(© Ute Mahler/Ostkreuz)

In those private situations you took photos of, the faces express something you could call an “inner freedom”. How was this inner freedom possible in a surveillance state?

Ute Mahler: We knew perfectly well that one out of three people was a Stasi member. But nothing much happened. We did our work, took photos and staged exhibitions. However, we did not go as far as the dissidents who became active in the late 1970s. The reason why people in the photos have such expressions? I think people had arranged themselves [with the system]. There was the official country and the inofficial one. Those people who today are nostalgic and who transfigure experiences are talking about inofficial, private life, about being with family and friends where people felt safe.

Werner Mahler: We were dealing with a country that treated us like children, that incarcerated us, and that limited our legal rights. I am convinced that East Germany was a dictatorship. But not to take photographs of such faces would suggest that in a dictatorship there can be no fun and no positive feelings about life.

Did you already experience this type of freedom that way back then, or do the faces only look free in retrospect?

Ute Mahler: On banners and in the official publications we were shown a socialist image of people. That was a bit obvious, and it was “loud” and superficial. It’s likely that that’s why we instinctively looked for another view. However, back then there was more trust between the subjects and me. Today, there exists a large amount mistrust concerning photography. You now know much better what you can do with photography, you know that photographs are not always just documents.

Werner Mahler: Almost all the photos we took were not designed for publication. The subjects knew that.

Ute Mahler: What is more, many photos were taken for us, not as part of a commission. I simply would wait a whole day for just one photo. That’s a huge luxury.

Concerning the discussions we have today about the fall of the Wall, what do you intend to say with the photographs you took back then?

Ute Mahler: Right now, there are so many publications about East Germany. What bothers me the most is that East Germany is portrayed as a funny, absurd, weird country. As, for example, in East German cook books. I mean, a cook book about East German cuisine is a joke! Or take the books about nudist culture. People always pick those strange areas, and then that is supposed to have been that country.

(© Ute Mahler/Ostkreuz)

(© Ute Mahler/Ostkreuz)

So where does the Ostkreuz photographers’ book fit in here?

Ute Mahler: If you talk about private life or about apartment complexes in Marzahn, it looks as if that’s so banal. But the small aspects of life determine the whole. It’s as if someone came to see Harald Hauswald and asked: “So tell me, what what is like back then?” Or to Sibylle Bergemann: “What happened there with the monument?” They wouldn’t need to say any words, because they made those wonderful images.

Werner Mahler: For a while, we considered to use “work” as a subject matter for all four photographers. But we abandoned that quickly, in part because we wanted to present ourselves as individual authors.

Ute Mahler: No, Werner, that didn’t work as a course for the book.

Werner Mahler: Well sure, it did work rather well.

Ute Mahler: It did not!

Werner Mahler: Alright, we don’t agree on that. But regardless, we also made our decision because we did not want to pretend that we were telling the story of East Germany. Even though we always say Ostzeit is a history book, it’s rather a book of stories. And if the stories make people reflect the history of East Germany we achieved our goal.

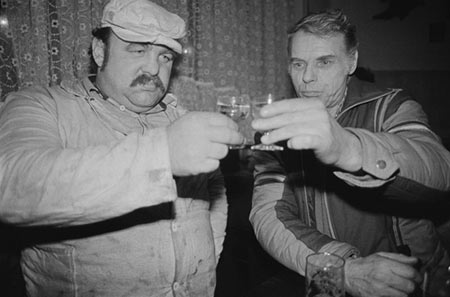

(© Werner Mahler/Ostkreuz)

(© Werner Mahler/Ostkreuz)

Which photos that were important for you back then did you omit, and what has become important for you now that might not have been in the past?

Werner Mahler: I can only talk about my own photos, my series about mining. Back then, I was only allowed to enter the mines three times, over the course of three days. Today, I think I picked a selection that looked a bit heroic. I was very impressed by the people down there. That was very tough work, you have no idea. There were two portraits of really great guys, where you thought “Damn, now that is a worker, that’s one personality!” Those photos I took out, and I replaced them with a portrait, which photographically is not so great: A portrait, using flash, rather big, very white face.

Ute Mahler: I really like that one.

Werner Mahler: Yes, but I don’t like it technically. Of course, I saw that back then, the lack of focus, too much flash. I just did not see the implications of that image. Now it’s part of the book, because when looking through my work my colleagues saw the second layer that has to be part of images. It’s what makes you wonder “Wow, what’s going on with that guy?” That whole series is now being presented in a completely different way than my edit back then. Concerning my work, that’s the most important change.

Ute Mahler: For me, it was a very personal decision to work on the project “Zusammen Leben” [“Living Together”]. I was interested in finding out how people can live together or not. I took out two or three photos because they are only important for me, but not for this country.

To what extent do your photos have an impact on your personal memories? And to what extent does the debate about East Germany eclipse your own photographs and memories? Is there a way to keep that separate?

Ute Mahler: My memories of East Germany exist though the images I took back then. Of course, there are memories that I did not take photos of, but the photos are what remains. I spent so much time with those images and the people in them. Not while taking the photos, but later, in the darkroom. You look at the contact sheets and decide to pick one, and you’re going back and forth with your loupe. And you then live with that photo for a long, long, long time, because it keeps getting enlarged, for example for an exhibition, or because you want to tell a new story. Some people have long forgotten about me, but for me they are part of my life.

Why is “Ostzeit” done in black and white?

Werner Mahler: It’s because Orwo’s colour film, which is all we had, stank. And we were professionals who had studied photography; we dealt with photography every day, and you simply can’t work with such a film.

Ute Mahler: Our projects start in 1972. During the 1970s and 80s b/w photography was still used widely all over the world. In West Germany, colour photography really only started in the 80s.

(© Sibylle Bergemann/Ostkreuz)

(© Sibylle Bergemann/Ostkreuz)

Did people understand your images the way they were intended?

Ute Mahler: Sibylle Bergemann’s photos of the Marx and Engels monument shows the two each with cleaning clothes over their heads in the sculptor’s studio. That every East German got. Or the wonderful photo where you can see the two figures sitting there in the park, and their heads are missing. That’s an imagery that everybody understood. The Ministry of Culture had commissioned this work, and they also saw the photographs. I don’t understand that they didn’t interpret them in the same way. I think they might have viewed them only in a documentary way - showing the making of the monument, the different phases of the work.

People often say that photography manages to move underneath the censor’s radar. What was the reason for that?

Ute Mahler: You have to be able to read images. Only few of those in power were able to do that. And if someone found something, we could always say: I don’t understand, this image only shows this and that. They had to prove that the symbolic part of an photo was intended the way it could be understood.

Were exhibitions your most important forum?

Ute Mahler: Yes, they were. I think I had 60 exhibitions back then, in Unterwellenborn, in Ruderstadt. I didn’t care whether the gallery was small or not.

Which of your photographs found their way into publications?

Werner Mahler: None of the topics we here published as a book; only occasionally one of the photographs [was published], for example in “Sibylle” magazine: very important, a magazine for fashion and culture. It really contained 50% fashion, 50% culture.

Ute Mahler: “Sibylle” did a few big articles about me. They published “Zusammen Leben”, also the photos about Paris, and fashion photos. And every now and then I had something in the “Sonntag” weekly. But that’s not what it was about for us, we didn’t take our photographs to have them published in newspapers. In the 1970s, we met Thomas Höpker, who was [West German magazine] “Stern’s” East German correspondent. And Höpker told me that for him a good photo is one that ends up as a double-page spread. I was surprised by that. For me, a good photo was one that I had at home in a box, that I would show to friends and colleagues, whose judgment meant a lot for me, and that I put into an exhibition. We made money with other things. Werner did advertizing photography, I took pictures of rock groups and fashion. But this [points to the book] was our lifeblood.

Which chances and risks resulted from the lack of pressure to publish your work?

Werner Mahler: Well, the big chance was that you did not have this pressure: If I don’t publish anything I don’t exist. Everything was based on our own interests, our own wishes, everything was based on our own desire to find out about what we took photos of and to preserve that for us. That might sound lofty. It’s about this kind of freedom and time which that a self-assigned job brings with it.

Ute Mahler: And it’s about being curious. We were so young back then. We had to know so much still.

Werner Mahler: We are often being asked what was special about East German photography. Maybe it’s the being curious, the intimacy, and the reduced role of the photographers. We just had the big Bob Lebeck, Thomas Höpker and Harald Schmitt exhibitions in Berlin. They are all three colleagues from the West, some older than we are. Almost all the works were photos that influenced world history. We couldn’t do that. We created a small, intimate, personal body of work.

(© Harald Hauswald/Ostkreuz)

(© Harald Hauswald/Ostkreuz)

Which photos from the West did influence you back then?

Ute Mahler: Well, of course we knew Josef Koudelka’s photographs from Prague. And his images from exile. For me, those were a big influence.

Werner Mahler: But also Frank und Bresson with their big humanistic approach.

Ute Mahler: But Frank is completely subjective.

Werner Mahler: Sure, but he respected the people.

Ute Mahler: … today, morality is seen as being so old fashioned. [laughs]

But it’s still valid for you today?

Ute Mahler: Of course. You have to be more careful, but sure!

Werner Mahler: After we started the “Ostkreuz” agency and became a bit known, which fortunately happened rather quickly, we said: We are not going to sell images to the Yellow Press. Everybody was surprised by this. But there was no way we would do that.

Ute Mahler: And we did not want any paparazzi photography.

Why did you start the agency that quickly anyway?

Ute Mahler: We realized immediately that a large fraction of the East German companies that paid for our work would not survive. And that’s how it came.

Werner Mahler: The agency was the best way to do both: the commercial part of photography under the new circumstances, and at the same time to keep what we wanted to keep - to work with people who thought like us. In the twenty years we have been around, we did four large exhibitions as an agency that show what we do apart from our commercial work. This also proves that we managed to present ourselves as photographers beyond the commercial work.

(© Werner Mahler/Ostkreuz)

(© Werner Mahler/Ostkreuz)

Is there still something like a personal order to do things?

Ute Mahler: I think the difference between the personal order to do things back then and now is that our photos were needed back then. It was very important to make those images and to exhibit them. People rushed into the exhibitions, and they were able to interpret their images.

Do you ask your students about their memories?

Werner Mahler: My job as a teacher is to discover the student’s talents and to point those out to her/him, so that after three years s/he knows her/his role as a photographer. If I manage achieve that I’ve done a good job.

Ute Mahler: Students ask when, for example, I’m talking about subjective photography. When I’m showing images talking about the past works. But I only talk about the past when the students as about it, and that happens very rarely. I find it interesting that modern/young photography often looks so distanced, uncannily reflective, detached. I am often under the impression they don’t really want to know all that much about another human being. Young photographers are very careful.

Werner Mahler: Maybe society as a whole these days really is this impassive, with so little desire to think about things.

Ute Mahler: It’s chilly and reserved.

Werner Mahler: You’re afraid to look into things, and too often you remain on the surface.

Ute Mahler: Because when you engage with people, you become responsible for what you do, and there might be consequences.

The reserved contemporary photography you were talking about is a consequence of the Düsseldorf photo school, founded by the Bechers. Are the Mahlers and the Bechers something like a German-German dialectic?

Ute Mahler: Don’t ask us about that.

Werner Mahler: It’s difficult to compare us with stars whose work is shown in all the major museums of the world.

Ute Mahler: Our temperament is different.

Werner Mahler: They had the idea to take photos of all those industrial structures that would disappear and to thus preserve them. The fact that a wonderful artistic work has evolved from that is great.

Ute Mahler: But when we started to take photos, we knew: This all here is going to stay this way forever. There never was the thought that there would some day be an end to the GDR.