Review: Neues Museum by Friederike von Rauch & David Chipperfield

Architecture forms one of the pillars of history, or at least of memory. Where there is no architecture, where there are no buildings, a sense of history is much harder - if not often impossible - to discern. History, of course, is not something (metaphorically) set in stone, whereas architecture usually is (remember, wooden buildings usually don’t last across the time scales history deals with). So when we change history - or maybe one would want to “write when we change the way we interpret and view the facts that form the foundation of history” - or when history itself changes, we often have to change our thinking about architecture as well. There are few places where this is more obvious than Berlin.

Architecture forms one of the pillars of history, or at least of memory. Where there is no architecture, where there are no buildings, a sense of history is much harder - if not often impossible - to discern. History, of course, is not something (metaphorically) set in stone, whereas architecture usually is (remember, wooden buildings usually don’t last across the time scales history deals with). So when we change history - or maybe one would want to “write when we change the way we interpret and view the facts that form the foundation of history” - or when history itself changes, we often have to change our thinking about architecture as well. There are few places where this is more obvious than Berlin.

Berlin is not a particularly old city for European standards. In 1987, it celebrated its 750th birthday, which makes it much younger than other large cities, be they German (Cologne and many other German cities date back to Roman times) or non-German (London, Paris, and of course Rome being obvious cases). Despite its relative youth, Berlin has gone through and symbolized a lot. Even if you only look back one hundred years, it was the capital of the German Empire, the ill-fated Weimar Republic, the so-called Third Reich, its eastern part served as the capital of the German Democratic Republic, and now it is the capital of the reunified Germany. During World War II, it was completely destroyed as a consequence of Allied bombs and the street fighting that resulted from the Third Reich’s leadership’s refusal to surrender. Nero let Rome go up in flames, Hitler did the same with Berlin. Divided after the war, Berlin was split in half, which included decades of literally splitting the city in half by means of a huge concrete Wall.

When the reunited Germany decided to move its capital from (sleepy) Bonn to (supposedly) cosmopolitan Berlin, there were lots of concerns about the new Germany - both at home and abroad - that had picked Berlin as its new face. Berlin’s architecture represented history, and not just any kind of history: It represented the history the new Germany was going to reject, while being carefully aware of it. Germany was not going to aim at becoming the same kind of power it had been in the past, and it was not going to forget about its past, especially in the light of the Holocaust.

Of course, there was a lot of prime real estate to be used. But how do you make use of buildings like the Reichstag or the former Reichbank? You can’t just move in and pretend as if nothing happened. But then you also can’t just tear these buildings down, because that would look like you just wanted to forget. Eventually, Germany settled on mostly very careful compromises.

One wishes, though, it would deal with its East German past as carefully and thoughtfully as with its Third Reich past: It is hard (but certainly not impossible) to understand how a country that preserved graffiti left by Soviet soldiers in its parliament would simply tear down East Germany’s former parliamentary building - using asbestos as an excuse - to (maybe) rebuild a palace that had been destroyed during World War II.

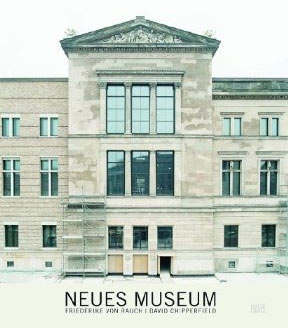

Regardless, one of the last big buildings to be brought back to life was the Neues Museum, which housed and will house Berlin’s famous Egyptian collection. After World War II, the building had been a ruin; and it was to be re-opened to contain the very same art it had presented before it got bombed out.

Neues Museum by photographer Friederike von Rauch and architect David Chipperfield presents the results of what turned out to be a conservation instead of a reconstruction. What was there was to be conserved, for reasons wonderfully laid out in an extended interview with the architect that is contained in Neues Museum

. And so the Neues Museum now looks almost oddly unfinished, yet at the same time it looks like a museum that is no historical oddity in this 21st Century - what a feat! Von Rauch’s photography of the almost finished building, still devoid of any of its historical artifacts, reveals the genius of the new Neues Museum.

Given its subject matter and the way it is presented, Neues Museum might be considered a book about architecture, rather than photography. It is both - and once you start thinking about what you see in the photos, it is also a book about history and its uses, and our relation to that history and to the buildings that surround us.